Prologue;

Sarah Broadhead's

Diary - July

2nd

"Diary

of a Lady of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania from

June 15 to July 15,

1863.

By Sarah M. Broadhead.

July

2. — Of

course we had no rest last

night.

Part of the time we watched the Rebels rob the house

opposite.

The family had left some time during the day, and the robbers must have

gotten all they left in the house. They went from the garret

to

the cellar, and loading up the plunder in a large four-horse wagon,

drove it off. I expected every minute that they would burst

in

our door, but they did not come near us. It was a beautiful

moonlight night, and we could see all they did.

July

2. — The

cannonading commenced about 10

o'clock,

and we went to the cellar and remained a little while until it

ceased. When the noise subsided, we came to the light again,

and

tried to get something to eat. My husband went to the garden

and

picked a mess of beans, though stray firing was going on all the time,

and bullets from sharpshooters or others whizzed about his head in a

way I would not have liked. He persevered until he picked

all,

for he declared the Rebels should not have one. I baked a pan

of

shortcake and boiled a piece of ham, the last we had in the house, and

some neighbors coming in, joined us, and we had the first quiet meal

since the contest began. I enjoyed it very much. It

seemed

so nice after so much confusion to have a little quiet once

more.

We had not felt like eating before, being worried by danger and

excitement. The quiet did not last long.

About

4 o'clock P.M. the storm burst again with

terrific

violence. It seemed as though heaven and earth were being

rolled

together. For better security we went to the house of a

neighbor

and occupied the cellar, by far the most comfortable part of the

house. Whilst there a shell struck the house, but mercifully

did

not burst, but remained imbedded in the wall, one half

protruding. About 6 o'clock the cannonading lessened, and we,

thinking the fighting for the day was over, came out. Then

the

noise of the musketry was loud and constant, and made us feel quite as

bad as the cannonading, though it seemed to me less

terrible. Very soon the artillery joined in the din,

and soon

became as awful as

ever, and we again retreated to our friend's underground apartment, and

remained until the battle ceased, about 10 o'clock at night.

I

have just finished washing a few pieces for my child, for we expect to

be compelled to leave town tomorrow, as the Rebels say it will most

likely be shelled.

I cannot sleep, and as I sit down to write, to

while

away the time, my husband sleeps as soundly as though nothing was

wrong. I wish I could rest so easily, but it is out of the question for

me either to eat or sleep under such terrible excitement and such

painful suspense. We know not what the morrow will bring

forth,

and cannot even tell the issue of to-day. We can gain no

information from the Rebels, and are shut off from all communication

with our soldiers. I think little has been gained by either

side

so far. Has our army been sufficiently reinforced?

is our

anxious question. A few minutes since we had a talk with an

officer of the staff of General Early, and he admits that our army has

the best position, but says we cannot hold it much longer.

The

Rebels do so much bragging that we do not know how much to

believe. At all events, the manner in which this officer

spoke

indicates that our troops have the advantage so far. Can they

keep it? The fear they may not be able causes our anxiety and

keeps us in suspense.

Has our army been sufficiently reinforced?

is our

anxious question. A few minutes since we had a talk with an

officer of the staff of General Early, and he admits that our army has

the best position, but says we cannot hold it much longer.

The

Rebels do so much bragging that we do not know how much to

believe. At all events, the manner in which this officer

spoke

indicates that our troops have the advantage so far. Can they

keep it? The fear they may not be able causes our anxiety and

keeps us in suspense.

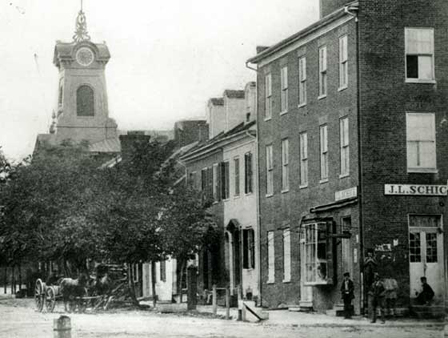

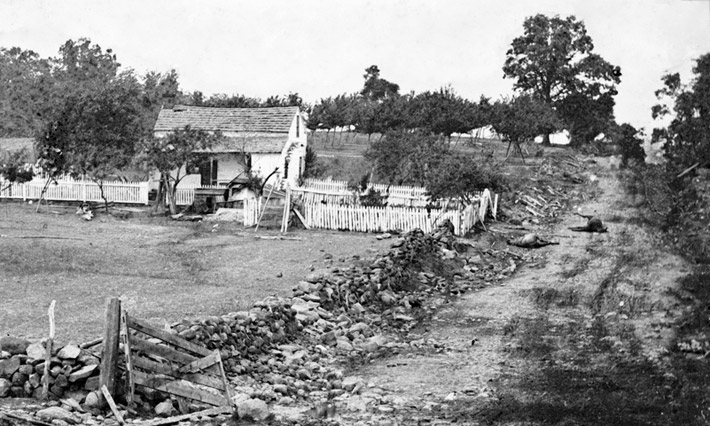

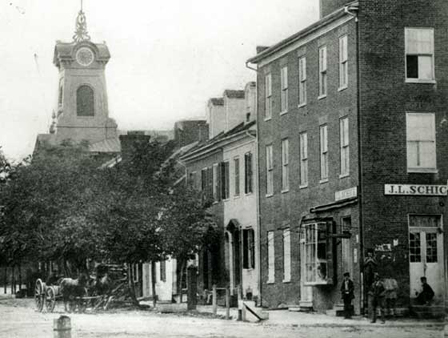

This photograph

was copied from the website "Gettysburg Daily." It

is believed the Joseph

Broadhead Family was living at 217 Chambersburg Street,

pictured on the right. The grey building next door, is the

David Troxell House. During the afternoon artillery duel,

Troxell's neighbors, including Sarah and her husband, gathered in the

basement of this home for safety. A shell struck the Troxell

house,

which can still be seen today. "This view was taken facing

northwest at approximately

2:00

PM on Thursday, January 1, 2009."

Return

To Table of Contents

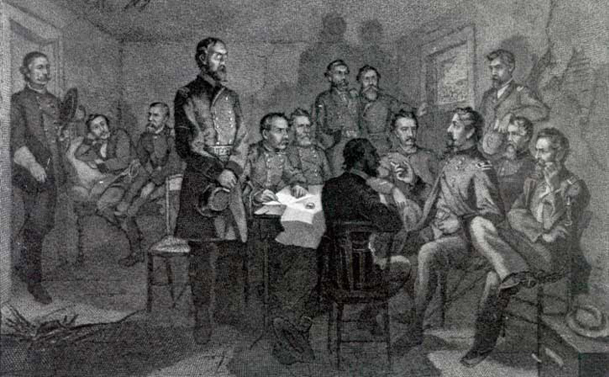

Introduction

While

the battle raged at Gettysburg, July 1st, Commanding

General George

G. Meade remained at Army Headquarters in

Taneytown, Maryland, to direct the concentration of the rest of

the army at Gettysburg. He sent trusted subordinate,

General

Winfield

Scott Hancock to the battle-field in his stead, to take

command of

the troops, monitor the day’s events, and report back to

headquarters whether or not the ground there was favorable for a

battle. But in the afternoon, before

hearing directly from Hancock, and once he was

convinced that

the enemy, General Robert E. Lee, was bringing his whole force to

Gettysburg, General Meade issued

orders to his several corps commanders to do the same.

In just 4 days, upon assuming command of the Army of the

Potomac, Meade

had gathered information, maneuvered the great scattered Army of the

Potomac north, and planned

for various contingencies depending on the enemy’s moves. A

tremendous accomplishment. Now

a great battle was imminent.

He remained at the Taneytown headquarters until

midnight, hoping to

meet with General

Sedgwick of the 6th Corps before departing, but delayed no

longer. He

had to get to Gettysburg 12 miles away, and prepare for the next days

fight.

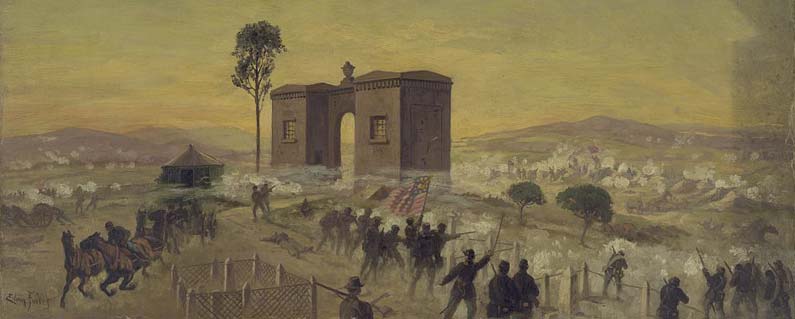

He rode up to the Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse on

Cemetery Ridge about

1 a.m. and was greeted by several of his generals with favorable

news. This was a good place to fight.

He was glad to hear that for “it was too late to

leave it.” 1

General Meade spent the rest

of the night, until early morning, riding the lines of his army,

accompanied by a staff engineer who mapped the terrain and noted the

commanding general’s intended troop placements. Chief of 1st

Corps Artillery, Colonel Charles Wainwright recorded in his

journal:

"General

Meade came along our line between one and two o'clock this morning.

General Hunt was with him, and I explained to him, as well as

I

could, the dispositions I had made here. It was not light

enough

to see much and they did not stop long."

Meade worried

that the enemy would attack before all was ready. He needed

day light to properly maneuver his several arriving army corps into

battle

positions.

Initially General Meade’s idea was to make a

strong attack on

the Confederates’ left flank from the area around Culp’s

Hill. In the morning he sent his chief engineer, General G.

K.

Warren off to examine the ground and report whether such an

attack

would be favorable. Then, he sent his son, George, as Aide,

to

check

on the 3rd Corps deployment at the left of the Union line. It

was the only corps that had not yet reported to headquarters.

As fate would have it, the fortunes of the Federal Army on July 2nd,

derived from the actions of 3rd Corps Commander, Major-General Daniel

E. Sickles.

General Sickles reported to General Meade’s son that he

was unaware, of

where precisely he was to deploy his troops. A quick

round-trip ride back to Headquarters, and the general’s son quoted

Meade’s instructions for General Sickles. “The Third Corps

was to go on the left of the Second Corps and prolong its line to

Geary’s position of the night before. (Little Round Top).

This was to be done as rapidly as possible.” 2

But, General Sickles was not happy with the ground

General Meade

assigned the 3rd Corps. That morning, he had agreed with one

of his aides that the high ground near the Emmitsburg Road was

preferable. Sickles rode to headquarters about 10 a.m., and

voiced his concerns. He requested General Meade accompany him

to examine the preferred ground. Meade refused being too

busy, but gave permission for his Chief of Artillery General Henry Hunt

to go. Before riding off, Sickles asked Meade if he could

place his troops where he saw fit. Meade replied, “Certainly,

within the limits of the general instructions I have given

you; any ground within those limits you choose to occupy, I leave to

you.,” 3

Major-General

Daniel Sickles, pictured.

The Chief of Artillery saw some advantages to the

advanced position

that Sickles wanted to occupy, but he also saw its fatal flaw, it was

twice as much ground to hold as that which was assigned, and it would

take many more men than Sickles had to hold it.

Hunt gave Sickles some suggestions as to where artillery might be

placed if the forward line was utilized, then left to tend to

his

own matters. On the way to Cemetery Hill Hunt stopped at

Headquarters and reported to Meade that Sickles' position ‘taken on its

own’ was strong, but that Meade should see it for

himself. 4

As morning gave way to mid-day, a continuing series of

miscarried communications between his own staff and head-quarters

irritated

General

Sickles. He believed his line was a better one to fight off

an enemy attack, and that head-quarters was ambivalent to the concerns

of the 3rd Corps and its commander.

When skirmishing broke out in the woods opposite his

favored position

about 1 p.m. Sickles abandoned Meade's intended line and decided to

advance his troops ¾ mile, to the high

ground on the Emmitsburg Road near the Sherfy family Peach Orchard.

The new 3rd Corps line over extended itself. It

covered too

much ground. It had gaps. It was made without the

knowledge of the troops that connected on the right, and it

severed that

connection. When General

Meade, who was not known for his mild temper, finally learned what had

happened, he blew a gasket, so to speak. An aide wrote, "I

have

never seen him so angry." Meade rode to General

Sickles'

line and

correctly observed, it could not be held by the 3rd Corps

alone. Sickles agreed, but continued to assert that in his

opinion it was the best line. An Aide to General Meade remembers his

answer to Sickles as, “General Sickles, this is neutral ground, our

guns command it as well as the enemy’s. The very reason you

cannot hold it applies to them.” 5

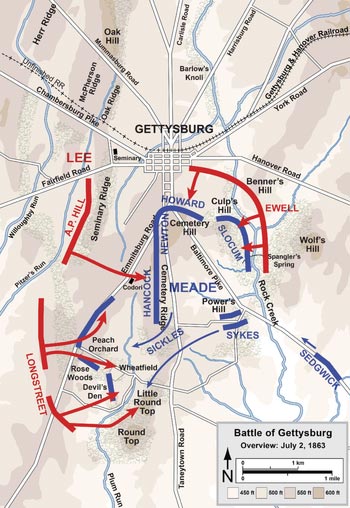

General Sickles

was ordered to anchor his line at the Round Tops and connect with

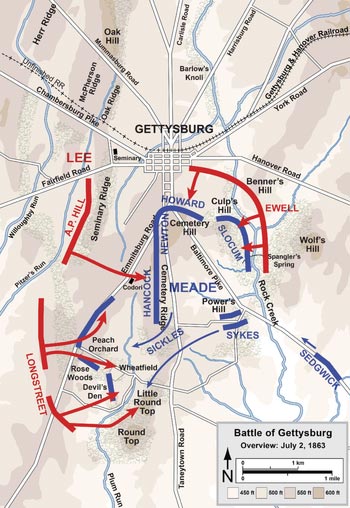

General Hancock's line on Cemetery Ridge. The map at left

shows the advanced line that General Sickles took up

without General Meade's knowledge. Consequently

General Meade had to rush troops onto the field to bolster Sickles'

vulnerable position. (Ewell's attack as depicted occured in

the evening.) The map is by Hal Jesperson,

www.posix.com/CW; from Wikimedia Commons.

Hearing this, General Sickles offered to return to the

ground first

specified. But the boom of enemy cannon announced it was too

late.6 It was after 3

p.m. The fight was about to begin.

The rest of the afternoon, during the course of intense

fighting on the 3rd Corps front, General Meade desperately shovelled

troops from the 2nd and 5th Corps into the battle ground chosen by

General Sickles.

If General Meade’s staff was negligent for not directing

Sickles into

position, Sickles advance was insubordinate. Fortunately for

General Meade, things weren't proceeding smoothly for those people

across the lines.

The Confederate Army had its own problems with planning

and deployment

on the morning of July 2nd. General Robert E. Lee’s planned

assault on the

Union left was based upon a deeply flawed reconnaissance report done

very early in the morning. Once begun, the

attack

had to be altered on the battlefield. General James

Longstreet, whose corps was to do the fighting, was against making the

attack at all. He considered the Union defenses too strong to

break. Confusion and poor supervision delayed the deployment

of Longstreet’s troops as they moved south into battle

position. The hours of the day passed away. It took

six hours before the planned Confederate attack began. But

once

underway, the

Rebels pushed hard and soon broke

General Sickles’s salient at the Sherfy Peach Orchard along Emmitsburg

Road. The rest of the 3rd Corps line eventually collapsed. In

spite of

success, the Rebel attack sputtered out as darkness fell.

For, after the tired but victorious Confederate troops swept the

Federals from the ground Sickles occupied, they faced another Union

line in a strong position along Cemetery Ridge. It was the

line

General

Sickles had initially been ordered to hold by General Meade.

It

was General Meade and his able subordinates who patched the new

defensive line

together, and saved the day for the Federals.

In the evening, another crisis would emerge to the

north, on the right

of the Union lines at Culp’s Hill, but more on that later.

NOTES

1. Coddington, Edwin

B., "Gettysburg

Campaign, A Study in Command", First Touchstone Edition,

1997; p. 323. Author Coddington cites: General

O.O. Howard for this comment, OR, XXVII, pt. 1, p. 705.

2. Pfanz, Harry W.,

"Gettysburg, The

Second Day, The University of North Carolina Press", 1987; p. 83.

Author Pfanz cites "Meade, Life and Letters of George Gordon

Meade," 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1913. p. 67;

Meade, "With Meade at Gettysburg," Philadelphia: John C.

Winston Company, 1930. p. 101; Meade Testimony, "Committee on

the Conduct of the War", p. 338.

3. Pfanz, p. 93.

Author Pfanz

cites: "With Meade at Gettysburg", p. 106; Meade Testimony, "CCW

Report", p. 328;

Sickles' Testimony , "CCW", p. 298.

4. Coddington, p.

345. Author Coddington

cites: CCW Report, vol. 1, p. 449-451.

5. Pfanz, p. 144.

Author Pfanz cites:

Major James C. Biddle to Meade, 18 Aug. 1880, Gettysburg Letter Book.

George Gordon Meade Collection, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, p. 27; Meade, "With Meade at Gettysburg",

p. 114.

6. Meade at Gettysburg etc.

Return

to Table of Contents

What's

On This Page

This Gettysburg page was another difficult page to

assemble. Not too much source

material exists from the 13th Mass., and that which exists is a bit

vague in

terms of battle-field deployments. Once again, the problem

was solved by looking beyond the regimental resources for information.

The page begins with a

citizen's perspective of the battle;-- Sarah Broadhead's prologue.

It is followed by a brief introduction that sets the stage

for the day's battle by looking at the controversy of General Sickles'

3rd

Corps deployment.

Then, an analysis of men and losses in Robinson's division

from the first day's fight is presented to show how depleted these

regiments were on July 2nd. The 13th Mass., now numbered

about 98 men, present for duty, down from 284 that entered the

battle. Following this is a brief look at the new

First

Corps Commander, Major-General John Newton. Newton's life

&

career up to the time of his appointment is summarized in the

section titled, 'A New Corps

Commander.' And then comes some stories from the 13th Mass.

The

section titled 'Battle Impressions of 3

Soldiers', presents some brief reflections from Sam Webster,

David

Sloss and William R. Warner on

the first days battle. Each account is short but considering

how few men of the regiment actually made it to Cemetery Hill to

participate in the battle on the 2nd and 3rd days, I am grateful to

have them. Lieutenant Warner made a list of Company K men

present at Gettysburg. I must thank Warner's

step-descendant Eric Locher for allowing me to use this excerpt of

Warner's manuscript on my website. The Gettysburg pages are

infinitely stronger in content because of it. Another

highlight of this section is the 1911 photograph of survivors of

Company K, taken from William Warner's scrapbook. Warner's scrapbook

came up for sale at an auction house in the fall of 2015, and

I was fortunate to get a good copy of this image. The page

continues with some excerpts from the writings of Major Abner Small.

Major Abner Small, was a lieutenant in

the 16th Maine at the time of the battle. This regiment,

somewhat of a 'hard luck' unit, served in the same brigade with the

13th Mass, for a long time. The fortunes of the two units

were often intertwined. And, Major Small's descriptive

narrative is exquisite. He was ordered to serve as Adjutant

for Colonel Richard Coulter of the 11th PA, who transferred out of

Baxter's 2nd Brigade to take command of Paul's

1st Brigade. Major Small gives some amusing insights into

Coulter's character. After the introduction to Colonel

Coulter the narrative for July 2nd, from the 13th

Mass., regimental history is given.

Charles Davis, Jr., borrowed heavily from William

Warner's diary for the brief

passage about July 2nd, so I include Warner's diary entries to begin

with. But,

both accounts are vague and I would say that Davis's brief statements

are

downright confusing for someone trying to track the

regiment's positions on the field of battle this day. To

remedy this, a series of hourly maps from battle-field historian John

B. Bachelder (1825-1894), are presented in the section, 'So, Where

exactly Were They on

July 2nd?' The maps show the specific locations

of

Robinson's division during the day, as recorded by Bachelder.

The essay also discusses

in general terms, the progress of the battle and why the

regiment/division was

moved around so much.

This

image shows the position held by

Paul's (Coulter's) Brigade the night of July 1st until the

morning

of July 2nd. Part of the brigade was out front at the blue

line.

The rest formed along the wall in the foreground, up to the

Bryan

house and barn, seen in the first picture. This was

the view the boys had when they awakened on the morning July

2nd, surrounded by troops of the 2nd Army Corps. It also

happens to be

the point on the Federal line reached by Rebel soldiers in Pickett's

Charge on July 3rd. Notice the Codori barn along

the Emmitsburg Road in the background. That is the place

where

the regiment

had turned from the road and rushed over the fields towards the

Seminary on the morning of July 1st. Click to

view larger.

The page changes gear for the final articles.

The interesting narratives of Private Bourne

Spooner and Sergeant Austin Stearns describe their different

experiences as

prisoners of war. Spooner is corralled with the rest of

the Union Army captives, but Stearns, is wounded, and so remained at

Christ

Church Hospital on Chambersburg Street. He was free to ramble

about the town within limits, and describes his wanderings and

encounters with Rebel soldiers. After looking in on the

prisoners, the narrative turns back to head-quarters with the section

titled, 'Council of War.' This is a follow up to the

introduction, with a look at Meade's gathering of Corps Commanders

following the heavy fighting of July 2nd. The article is

written

by one of the participants, Brigadier-General John Gibbon of the 2nd

Corps.

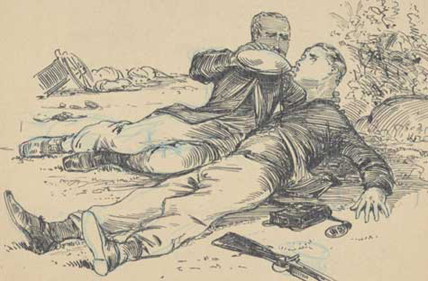

After this, the page

concludes with a

short story "Lost Among the Dead" found in Bivouac Magazine, 1885.

It is a fictionalized account of a soldiers

experience based on the real experiences of author G.F. Williams, who

was both a soldier and a war correspondent. The story

reinforces the idea, often lost amid stories of valor, that this war

was in fact a horrible thing. -- I hope you will enjoy this

page.

PICTURE CREDITS:

All images & Maps are from

the Library of

Congress digital images collection, with the following

exceptions: Sarah Broadhead is from the blog, "In The Swan's

Shadow",

http://theebonswan.blogspot.com/2013/06/sarah-broadheads-battle-narrative-of.html;

The

David Troxell House from Gettysburg Daily,

http://www.gettysburgdaily.com/gettysburgs-david-troxell-house-artillery-shell/;

Cemetery

Gate House, & battle-field dead, (Sepia photos by Timothy

O'Sullivan) from the Chrysler Museum of Art, Digital Photograph

Collection; Gettysburg Battle Map,

July 2nd by Hal Jesperson, accessed by Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of David Sloss was shared with me by Mr. Scott

Hann; Charles Reed sketch of canteen burdoned soldier accessed

digitally from "Hard Tack & Coffee," by John D. Billings;

accessed digitally via google books. Major Abner R.

Small, 16th

Maine, from

"Road To Richmond" edited by Harold A. Small, University of

California Press, Berkeley, California, 1939; Frank Schell's

sketch of an exploding

shell and John Allen Maxwell's sketch of a Rebel Soldier (in Austin

Stearns section) from Civil War Times Illustrated;

Copies

of the

Bachelder Maps are from Mr. Bob George and Mr. Steven Floyd of

Gettysburg; Evening photographs by Buddy Secor, his pseudonym

'Ninja Pix" used with permission. Other snapshots of the

battlefield were taken by Susan Z. Forbush, June, 2016;

Sergeant

Bourne Spooner presented by his

descendant, Mr. Will Glenn;

"Louisiana Pelican' by artist A.C.Redwood, & Edwin Forbes

sketch,

'Confederate Attack on Cemetery Hill,' from Battles &

Leaders of the Civil

War, Century Publications, 1887-1888; Portrait of John Flye

and Dan Warren, from author's private collection;

Charles Reed sketch of soldiers sharing a canteen from the

New York Public Library digital collections; ALL IMAGES HAVE BEEN

EDITED IN PHOTOSHOP.

Return

to Table of Contents

Robinson's

Division;

Strengths & Losses

The first day's fight at Gettysburg was looked

upon

as a Union defeat, although the First Corps troops fought

brilliantly

against a superior force of the enemy and gained time for the Union

Army to consolidate at Cemetery Hill. It was a delaying

action. Though they took a

licking, the First Corps soldiers never considered themselves

whipped. Their comrades in the army also knew that they had

fought

well. In fact, as Charles E. Davis, Jr. wrote of the first

day’s battle, “We saw at once that we had stayed at the front

a little

too long for our safety. Some of us were to be gobbled and

sent to rot in rebel prisons. Over fences, into yards,

through gates, anywhere an opening appeared, we rushed with all our

speed to escape capture.” First corps losses figure about

49.6 % in killed wounded and missing men.

General Robinson's 2nd Division suffered a loss of

56.4% in men

killed, wounded, captured or missing. The loss in

captured

or missing men from

Robinson’s Division accounted for over half these numbers.

Eleventh Corps casualties by comparison, were

lower. Once again like at the battle of Chancellorseville,

this unlucky corps was caught in an

indefensible position, and hit hard on the flanks by a superior enemy

force. And, like

at the Battle of Chancellorsville, it was abruptly compelled to leave

the field. Because the majority of troops in the 11th Corps

were of German ancestry, it earned the unwelcome sobriquet of

“The

Flying Dutchmen.” It would have to suffer its bad reputation

a while longer. As the tattered remnants of the First and

Eleventh Corps scrambled on to Cemetery Hill, in the late afternoon

hours of

July 1, an officer directing the troops into their new

respective positions was heard to say, “First Corps goes to the right

and Eleventh

Corps go to hell.”1

In Consequence, of the heavy losses racked up in

the first day's battle, the shattered troops of the First Corps, were

held in reserve during the 2nd and 3rd days' fighting.

Union losses for the day, were dutifully reported

at the

regimental level, though

they were done so with, not

unexpected errors. From these reports,

brigade

and division losses could be generally determined. But unit

strengths going into the battle at the regmental and brigade

level

are a trickier thing to tabulate. In order to give an idea

of First Corps' losses, and those of General Robinson's

2nd Division, a few

sample tallies are hereby presented.

Numbers,

Numbers, Numbers

Official

Reports for the battle give army strengths at corps and division

levels. It is more difficult to determine unit strengths at

the

smaller brigade and regimental level.

Several

attempts to determine division and brigade strengths at the Battle of

Gettysburg have been made over the years. General John

Robinson

himself,

reported his division went into battle with 'less than 2,500 men, and

lost 1,667 in killed, wounded and missing.' As time passed,

others

took pains to compute the actual numbers of men engaged in the great

battle.

Among these are John Mitchell Vanderslice, an

Executive Board Member of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial

Association. The Association formed in 1864, dedicated to

preserving the historic battle-ground and its legacy for future

generations. In 1895, Vanderslice was chosen by the Board of

Directors of the association to write a concise history of the battle

due to the knowledge he gained working with veterans on the GBMA

monument commission.2

In his work, Vanderslice admitted that the numbers

reported during the battle were inaccurate, but in many

instances

corrections were made to the battle-field monuments, within certain

restrictions. The following chart includes numbers taken from

the monuments. Other sources used in the chart below include

Century Publications historic work "Battles & Leaders of the

Civil War," 1884-1887. And, John Vautier's work, "A

Discursive Chapter on the First Day at Gettysburg", a careful study of

the battle that is included within the regimental history of the 88th

PVI.3

In more recent times, historians David

G. Martin with John W. Busey attempted a serious analysis of the data

and came

up with their own numbers. The 'Busey & Martin'

numbers presented here were printed

in Steven A. Floyd's book, "Commanders and

Casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg."

The

following charts are presented to give a general idea of the numbers

and losses of Robinson's Division and to show the discrepancies in a

select sampling of source material.

Robinson's

Division; Strength & Losses

| Source |

Strength |

Killed |

Wounded |

Missing |

Total

Losses |

| General

Robinson's Report |

2,500 |

x |

x |

x |

1,667 |

| Busey

& Martin 2005 ed. |

2,995 |

91 |

616 |

983 |

1,690 |

| Battles

& Leaders of the CW |

x |

90 |

613 |

933 |

1,681 |

| John

M. Vanderslice |

3,248 |

707

k/w |

982 |

1,629 |

| Gettysburg

Monuments |

3,133 |

116 |

592 |

972 |

1,680 |

| John

Vautier |

2,764 |

x |

x |

x |

1,525 |

I've compiled data to make the following charts

which show

the discrepancies in regimental strengths as recorded in a variety of

sources. The source list is provided below the charts.

General Paul's 1st

Brigade,

Regimental Strength;

| Regiment |

O.R. |

Vanderslice |

State

Commissions |

Regimental

History |

Monument |

Busey

& Martin |

| 16

ME |

x |

298 |

30/350* |

25/267 |

25/250 |

298 |

| 13

MA |

260 |

x |

x |

284 |

284 |

284 |

| 94

NY |

x |

x |

30/415 |

x |

445 |

411 |

| 104

NY |

x |

x |

330 |

x |

309 |

285 |

| 107

PA |

25/230 |

255 |

25/230 |

x |

25/230 |

255 |

| Totals |

x |

x |

x |

x |

1,568** |

1536*** |

General

Baxter's 2nd Brigade, Regimental Strength;

I could not find any

mention of unit strength for any of Baxter's regiments in the O.R.

| Regiment |

O.R. |

Vanderslice |

State

Commissions |

Regimental

History |

Monument |

Busey

& Martin |

| 12

MA |

x |

x |

x |

about

200 |

301 |

261 |

| 83

NY |

x |

x |

215 |

less

than 200 |

215 |

199 |

| 97

NY |

x |

x |

255 |

24

officers/? men |

255 |

236 |

| 11

PA |

x |

292 |

292 |

212 |

23/269 |

270 |

| 88

PA |

x |

296 |

296 |

less

than 300 |

294 |

273 |

| 90

PA |

x |

208 |

208 |

208 |

208 |

208 |

| Totals |

|

|

|

|

1,565 |

1,451*** |

The

13th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

Charles

Davis, Jr. wrote in the regimental history of the 13th Mass., "Of the

two hundred and eighty-four men and officers

we took into the fight, only ninety-nine now remained for duty, the

casualties being seven killed and eighty wounded, a total of

eighty-seven. In addition to this number ninety-eight men

were

taken prisoners on their way back through the town."

*In Maine

at Gettysburg, Major Abner Small writes, "It will be

observed

that the list above given presents a total of 100 more men and six more

officers than the numbers given respectively in the inscription on the

monuments. ...in regard to the officers...those of the field

and

staff were inadvertantly omitted in making up the account for the

inscription" Major Small says that one of the six officers on

staff was

absent sick. He continued, "With regard to the discrepancy in the

two reports of men present, ...the numbers given in the inscription are

those reporting present for duty at the last roll-call before the

battle. It is certain that men came up at some time during

the

three days battle. But it is believed to be more nearly just

to... [include] ...some who were not in the battle than to leave off

some because there is no other proof of their being present..."

**Mostly

on the First Day.

***The

Totals add up to 1,533 for Paul & 1,447 for Baxter. 3

& 4

extra officers and men respectively, on staff and command, are added to

the totals.

SOURCES:

Official

Records of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 27. Part 1;

p. 289-312.

Gettysburg

Then and Now, by John M. Vanderslice, A

Director of the Memorial Association, New York, G.W. Dillingham Co.,

Publishers; 1899; p. 124.

State

Commissions: Maine

at Gettysburg, Report of Maine Commissioners

prepared by the Executive

Committee, 1898; p. 42, & 51-58. New

York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and

Chattanooga. Final Report On The Battlefield of Gettysburg, Albany, J.B. Lyon

Company, Printers 1900, Vol. 1., p. 108. Pennsylvania at

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania Battle-field Commission, 1914, Vol. 1, p.

172-173.

Regimental

Histories: The

Sixteenth

Maine Regiment in the War of the Rebellion 1861 - 1865, by

Major A. R. Small; B. Thurston & Company, Portland, Maine,

1886; p. 114. Three Years

in the Army, The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers,

by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Estes & Lauriat, Boston, Mass. 1894;

p. 229. History

of

the Twelfth Massachusetts Volunteers (Webster Regiment),

by Lieutenant-Colonel Benjamin F. Cook, Published by the Twelfth

(Webster) Regiment Association, Boston, 1882; p. 102.

History

of

the Ninth Regiment- N.Y.S.M. - N.G.S.N.Y. (Eighty-Third N.Y.

Volunteers.) 1845-1888.

Historian George A. Hussey. Editor William Todd, Published

under

the auspices of Veterans of the Regiment. New York 1889; p. 287.

History

of The Ninety-Seventh Regiment New York Volunteers, ("Conkling

Rifles,") In The War For The Union,

By Isaac Hall, Utica, NY, Press of L.C. Childs & Son,

1890;

p. 142. note: if Major Hall gave numbers of enlisted men engaged, I

missed it, when copying pages from the regimental history - B.F.

The

Story of

the Regiment, By William Henry Locke, J.B.

Lippencott

& Co., 1867; p. 243. History of

the 88th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War For The Union, 1861-1865,

by

John D. Vautier, Co. I, 88th P.V.; 1894; p. 105.

Reunions

of the Survivors of the Ninetieth Penna. Vols. (Infantry) on the

Battle-field of Gettysburg., Survivors

Association, Gettysburg,

1888-89; (90th Pennsylvania Volunteers.) By Colonel A. J.

Sellers, President of the Association; p. 32.

Regimental

Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, by John W. Busey and

David G. Martin, 2005 edition, as cited in "Commanders and Casualties

at the Battle of Gettysburg, by Steven A. Floyd.

NOTES:

1. John D. Vautier Diary, July 1, 1863, Vautier Papers,

USAMHI. As cited in, Gettysburg -

The First Day, by Harry W. Pfanz, p. 332.

2. Gettysburg

Then and Now, by John M. Vanderslice, A

Director of the Memorial Association, New York, G.W. Dillingham Co.,

Publishers; 1899; p. 24. Vanderslice's

position and responsibility for most of sixteen years was as

a

member of the Executive Committee and Secretary on the Location of and

Inscriptions on Monuments. In 1895 the GBMA selected

Vanderslice

to 'briefly and accurately describe the position, movement, services,

and losses of every regiment and battery engaged in the battle, as

established by the information gathered and collated by the

Association, by the official reports, and by statements of officers and

men of both armies, who, by its invitation upon several occasions met

and conferred upon the field for the purpose of marking the lines of

battle, which statements have been most carefully examined, compared,

and verified."

3. History

of the 88th Pennsylvania

Volunteers in

the War For The Union, 1861-1865, by John D. Vautier, Co.

I, 88th PV,

1894. p. 152.

Return

To Table of Contents

A

New Corps Commander

Major-General John Reynolds was killed and the

First Corps

needed a new leader. General Meade appointed Major-General

John Newton to the command. In doing so he

superseded General Abner Doubleday, the ranking First Corps

officer. Doubleday commanded the corps in battle on July 1,

following

Reynolds’ death. But Meade had doubts about Doubleday's

ability to command a corps.

These doubts likely were reinforced by two dispatches

from the

battlefield received at Headquarters at Taneytown on July first.

The first dispatch came from General John Buford, the

exceptional

cavalry commander whose skilful deployment of troopers opened the

battle. Buford wrote at 3:20 p.m. July 1st, “…a

tremendous battle has been raging since 9:30 a.m. with varying success…

General Reynolds was killed early this morning. In my opinion there

seems to be no directing person. P.S. We need help now.”

Buford’s dispatch reveals his lack of faith in Generals

Doubleday and

Howard the senior officers then commanding the field. The

2nd

paragraph in the following message probably didn’t help Doubleday

either:

July 1, 5.25.

General:

When I arrived here an hour since, I found that

our troops had given up the front of Gettysburg and the town.

We have now taken up a position in the cemetery, which cannot

well be taken; it is a position, however, easily turned.

Slocum is now coming on the ground, and is taking position on

the right, which will protect the right. But we have as yet

no troops on the left, the Third Corps not having yet reported; but I

suppose that it is marching up. If so, his (Sickles's) flank

march will in a degree protect our left flank. In the

meantime Gibbon had better march on so as to take position on our right

or left, to our rear, as may be necessary, in some commanding position.

Gen. G. will see this despatch. The battle is quiet

now. I think we will be all right until night. I

have sent all the trains back. When night comes it can be

told better what had best be done. I think we can retire;

if not, we can fight here, as the ground appears not

unfavorable with good troops. I will communicate in a few

moments with General Slocum, and transfer the command to him.

Howard says that Doubleday's command gave way.

Your obedient

servant,

Winfield

S. Hancock,

Maj.

Gen'l.,

Com'd'g. Corps.

General Warren is here.

A multitude of other pressures upon General Meade at

this time, coupled

with his own suspicions about Doubleday, convinced him to

make

a change. Meade was given the power from authorities in

Washington D.C. to appoint whomever he wished to command, regardless of

seniority,

At 4:30 Head-quarters sent out an order to the 6th Corps

instructing

General Newton to come forward and take command of the 1st Corps.

Coming from another corps, General Newton was an unknown

commodity to

the men.

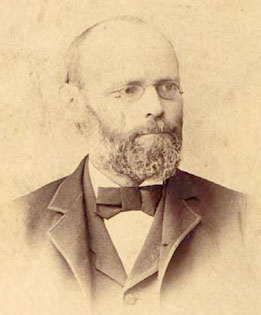

General

John Newton

Newton was a Virginian, born August 24,

1823. His father was a long time

member of the House of Representatives. John Newton showed a

proficiency in math at an early age and was tutored with the intent

of

becoming a civil engineer. At age 18 he entered the military

academy at West Point. He graduated 2nd in his class in

1842. He served the military in the Corps of Engineers and

spent most of his pre-war years in the planning and construction of

military forts from the New England Coast to the Great Lakes and the

Gulf of Mexico. One of his earliest construction assignments

was at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. He slowly gained rank

during his long military service. He was Captain of Engineers

when the war broke out in April, 1861, and he made the distinctive

decision to remain loyal to the Union. In his own words

regarding this decision he made the following statements to artist

James E. Kelly in January, 1895:

“The Regulars [before the war] used to have great

discussions about

disunion. I remember we used to talk it over and I said:

“There is no use arguing. Let us think it over for a

month.” We did so, and we met and I said: “Now for the

Constitution, it doesn’t matter what it says – it is a quarrel of

patriotism. I don’t care what George Washington says; I don’t

care what John Adams says; I must think for myself as a man. The

country has ceased to be a collection of individual states, and has

become one country. I must judge things as they are, not as

they were, and I propose to stand by the Union.”

Captain Newton continued to serve as Chief Engineer in

the Department

of Pennsylvania, and later in the Department of the Shenandoah. During

the winter of 61-62 he was involved with the planning and construction

of forts for the defenses of Washington. But he left the engineers in

the Spring of 1862 to take part in the Peninsula Campaign with the Army

of the Potomac. With the rank of Brigadier-General of

Volunteers he commanded a brigade and proved himself particularly adept

at handling troops in the field in June of that year.

A great field success for him, came at South

Mountain on

September 14th, at the

Battle of Cramptons’ Gap. General Newton led his

brigade in a bloody bayonet charge that in co-ordination with others,

helped to rout an obstinate Confederate enemy from their

stronghold. It was a decisive victory for the

Union. General William B. Franklin, his Commanding officer

recommended Newton for promotion in his official report:

“While fully concurring in

the recommendation offered in behalf of

Colonels Bartlett and Torbert, who have certainly earned promotion on

this as on other occasions, I respectfully and earnestly request that

Brigadier-General Newton may be promoted to the rank of major-general

for his conspicuous gallantry and important services during the entire

engagement.”

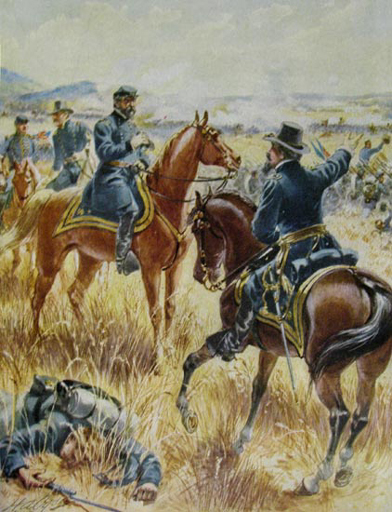

Pictured

is, "Franklin's Corps Storming Crampton's Pass" by A.R. Waud,

Harper's Weekly, October 25, 1862.

A month later General Newton was given the command of a

Division in

the 6th Corps. But following the disastrous defeat of the

army at Fredericksburg, he stepped outside the bounds of good conduct

and military discipline.

At the time there was abundant loose talk in the high

command on the

lack of faith in the abilities of commanding general Ambrose Burnside

to lead the Army of the Potomac. Burnside was planning

another

river crossing when General Newton and one of his brigade commanders

decided to voice their concerns to authorities in Washington.

This was against military protocol, in which it would have

been

better for the senior commanding officers to worry about such

matters.

During an awkward interview with President Lincoln, General Newton

tried to explain the de-moralization of the army under Burnside’s

command. The gentleman with him, brigade commander,

John

Cochrane, was more direct and

critical of Burnside during the interview with Lincoln. The

difficult meeting added to President

Lincoln’s worries regarding divisive factions within the Army of the

Potomac at a time of crisis, when repeated military defeats caused

Northern morale to slip, and opponents of the war to become

more

vocal. Burnside was eventually removed, and General Newton

remained, but his part in the drama would later hurt his military

career.1

Nonetheless, he was promoted Major-General of Volunteers

in March

1863. To quote from John Hoptak’s short biography of General

Newton :

“…he led his division in attack against the Confederate

position along

the base of Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg during the

Chancellorsville Campaign. He was slightly wounded during the storming

of the heights, and his men suffered tremendous loss with casualties in

his three brigades exceeding 1,000 killed, wounded, and missing, about

one-third the division’s total number.”2

This was his career so far, when General Meade calld

upon him to

replace John Reynolds in command of the First Corps.

NOTES:

1. A year later

when the army was

re-organized, General Newton was temporarilly left without a command.

A week later the recommendation for his promotion to

Major-General was withdrawn. He later obtained a command with

Sherman,

etc. It is possible he was removed for being 'squishy.'

2.

[John Hoptak's blog]

http://48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com/2009/04/major-general-john-newton.html

Return

to Table of Contents

Battle

Impressions of 3

Soldiers

There

is not a lot of source material in my collection from the

ninety-nine men of the regiment that made it to Cemetery Ridge on July

1st. But the three accounts I have are very good - if all too

brief. Here are Sam Webster, Company D, David Sloss, Company

B,

and William R. Warner, Company G & K.

Diary

of Sam Webster

Diary

of

Samuel Derrick Webster; (HM 48531) Excerpts

of this diary are used with permission

from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

Thursday, July 2nd, 1863

Second Corps came up last

night, and was

placed to our left, extending toward the Round Top. This

afternoon, as

the 5th Corps was arriving, the rebels opened toward Round Top,

and a

heavy fight took place there, they being beaten woefully. The

12th

Corps got here last night also, and were put to the right of the 11th

Corps, with their right flank drawn back towards the Baltimore

turnpike. The Sixth Corps (6th) came up late in the evening, and

was

held in reserve. Our fellows, likewise, were withdrawn to

reserve, in

rear of cemetery. Morris, Color Sergt, was killed yesterday,

and

Davie

Schloss, of the State flag was knocked down by the arm of one of 14th

Brooklyn, who was torn to pieces by a shell. His brains were

scattered

over the flag. Davie got up again, and took his colors,

however.

Quite a number of our officers were taken yesterday.

Letter

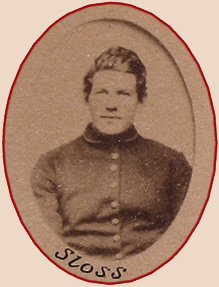

of David Sloss, Company B

Mr. James

Perry, David Sloss's descendant, found this letter and shared it with

me. Its source is the book Life

and

Letters of Alexander Hays, Pittsburgh, PA, privately

published 1919 p.

708; Fleming, George Thornton, ed; Hays, Gilver &

Adams, Company;

Pittsburgh PA. Mr. Perry still has a piece of the State Flag

his ancestor faithfully carried in battle.

Gettysburg Battlefield, July 5, 1863.

Dear Mother:

I wrote you a few lines about the first day’s

fight in

which our corps was engaged, but could not get it off until yesterday,

so I thought I might tell you some more about this battle, as it is

ended now, the ‘Rebs’ having left last night.

After getting out of the fight of the first day we

were

brought back of the town to support batteries in the cemetery until the

2nd day of July, when just about dark the Johnnies tried to turn the

left, and came very near being successful, but our division — eight

hundred men — were brought to bear on them and had a good effect by our

presence. As we went down the line everything looked like

Bull

Run, ‘Johnny Reb’ was trying his best to make it one by his fierce

shelling. The regiment ahead of us had seven men taken out by

a

solid shot.* Caissons and artillery stood out in bold relief

against the sky, without a horse or man near them. The

remnants

of regiments were taking off disabled guns, and everything looked blue

for our side, but the Rebels had been severely punished as well, and

they could not follow up their advantages. Our presence had

been

sufficient, so we went back to the graveyard and laid near the town

road. After night their pickets were very troublesome, but,

as we

were behind a stone wall, they did us no damage.

In the morning they commenced on the fifth, and

had

some very hot work with the Twelfth Corps. About noon they

commenced a terrible cannonading, and swept the hill upon which the

graveyard was, so that our safest place was right in front of our

batteries, and their batteries played on us and their sharpshooters

troubled us from the tops of the houses in the town. We lost

two

men by them. Added to this the sun came out terribly hot, and

a

lot of the division were affected by it. They commenced a

charge

about this time, and we were ordered under there fire to double-quick,

and away we went around the hill to help the Second Corps.

Colonel Coulter was hit, but not bad. He is in command of

our

brigade since Paul was shot. We just got in in time to see

the

‘Rebs’ break. It was a glorious sight to see, even if the

canister and shell were coming in thick, ‘old Hays,’ as his

boys

call him, ride up and down the lines in our front, with a Rebel flag

trailing on the ground. Such a wild hurrah I have never

heard,

nor saw such a sight, and never expect to see it again.

We immediately threw out skirmishers to cover the

field, but did not

advance. We laid flat on our faces so that they could not

trouble

us. They tried to advance on our left after this, but

succeeded

no better, as our line was so short across that we could easily

reinforce from left to right.

Dave.

*The shell fell amongst the men of the16th

Maine. More on

that later on this page.

Diary

of Lieutenant William R. Warner

Warner's

step descendant Mr. Eric Locher gaciously allowed me to present the

following Gettysburg excerpts from Warner's unpublished memoirs.

Warner's reminiscences skip around a bit from day 1 to day 2

and

so forth, so I have made a few edits to give them a little more order.

In view of the fact that

our Division on 2nd

& 3rd day, though constantly under fire

were owing to their

severe losses on 1st day and reduced numbers,

not placed in front

lines of battles, except as temporary supports, the writer has not

attempted

any detailed Account, even of matters which came directly under his

observation. — His

aim has been to

record a few impressions,

leaving descriptions to

those who had a more

active part. He

following his experience

about going under fire each day at Gettysburg. And I judge it

was

the

same with each of his

comrades. On 1st day, I think, when we heard of

Reynold’s death,

every man made up his mind, a battle was surely to be fought, but

events

followed so rapidly — the hasty throwing up of entrenchments at

Seminary, — the

brisk move to Oak hill, and we were under fire almost before we knew it.

Then

busy work put an end to

much thought about danger.

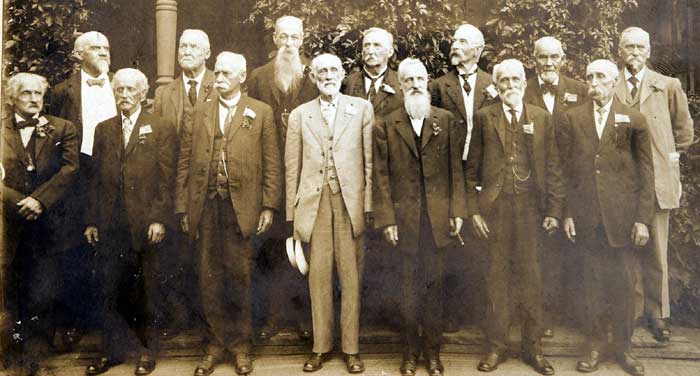

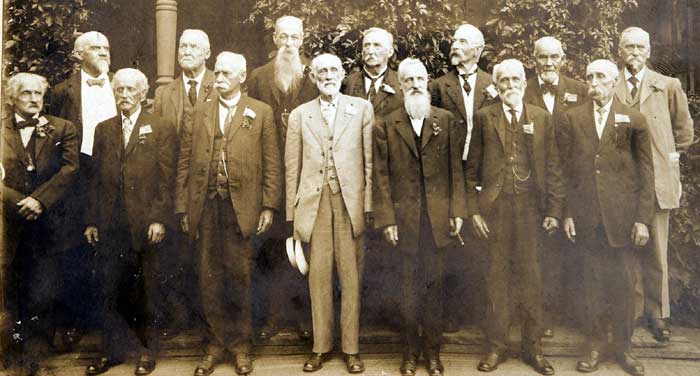

William

R. Warner's Scrapbook, came up for auction in the Autumn of 2015.

This image of 'Survivors of Company K, Taken at Westboro',

1911

was among those digitized. I have cropped the image.

Pictured left to right, are

J. C. Thurston, W. R. Warner, Lyman Haskell,

Ira L. Donovan, Melville Walker, A. E. Chamberlain, John D. Plummer,

Frank Brigham, Frank Wilson, C. W. Comstock, A.C. Stearns, Lowell T.

Collins, Warren W. Day, & George W. Cliffords. Some

of these men

are listed in Warner's journal under his roster of Company K men

present at Gettysburg.

Members

of Co K, present at Battle

of Gettysburg

Captain

Charles H. Hovey – On

Staff duty – Wounded

1st

Lt. David Whiston

Taken Prisoner

1 st

Lt. Samuel E. Cary,

“

“

1st

Lt. William B. Kimball, Former Member but

transfer to Co. A [pictured, right]

2nd

Lt. William R.

Warner “

“

“ Co.

E [pictured above]

Sergeant Willard Wheeler —

Killed

Sergeant A. C. Stearns Slightly

Wounded. [pictured above]

Corporal M. H. Walker Wounded

[pictured above]

H. A. Cutting — Wounded — Died

John Flye — Wounded — Died

M. O. Laughlan — Wounded — Died

Frank A. Gould —

Wounded — Died

George E. Sprague —

Wounded — Died

Charles M. Fay — Wounded

Slightly

L.

Vining — Wounded Slightly

Harvey

C. Ross — Wounded

Sergeant

William Rawson Taken

Prisoner

Corporal

James Slattery Taken

Prisoner

Corporal

A. L. Sanborn Taken

Prisoner

John

F. Bates Taken

Prisoner

George

W. Clifford Taken

Prisoner [pictured above]

Samuel

Jordan Taken

Prisoner

George

W. Hall Taken

Prisoner

Charles

F. Rice Taken

Prisoner

George

H. Seaver Taken

Prisoner

Henry

C. Vining Taken

Prisoner

Edwin

C. Dockham

Frank

P. Wilson [pictured above]

Otis

Drayton

John

M. Hill

L.

Haskell [pictured above]

C.

W. Comstock [pictued above]

John

Glidden — Pioneer.

A.L.

Sawyer — Drummer

Michael

Lynch — Detached duty in Battery.

While halted near the Seminary, Lt. Whiston

detailed Charles

M. Fay & Otis Drayton to fill the canteens of the

Company. (K)

Fay’s recollection of it in 1885 is that there

were 27 of

them, which nearly accords with this list. It

is possible that several had all the water

they wished.

Fay states that they found a well at Seminary

& a crowd

getting water.

Leaving Drayton

to watch the pile, he filled them, a few at

a time. When they

had left [for] the

Regt. they found it gone, and followed on with their immence load of 27

canteens catching up, in the woods.

As showing in one

instance, how well the men stood up to

their work. I

recall that when order was

given, by which the Regiment came into line of battle &

immediately under

heavy fire, Company K being the extreme left Company had

quite a

distance to run, & in

coming into line, the files crowded each other rather

closely.

George Seaver of Co K, a

little fellow,

familiarly known as “Unkle

Nat” lost his

place & ran up & down, past his own & also Co

G, at least twice,

trying to get into his place. Finally some one grabbed him,

made an

interval

& he took his stand.

Return

to Top of Page

Colonel Coulter

Takes Command of Paul's

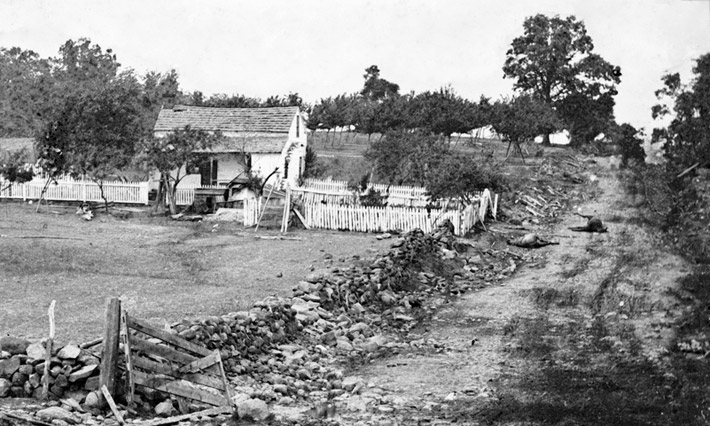

Brigade

The morning of

July 2nd, Colonel Richard

Coulter of the 11th PA was ordered by General Robinson to take command

of General Paul's 1st Brigade. General Paul was permanently

out of action with a fearful wound to his head. Colonel

Leonard

of the 13th Mass., and Colonel Root of the 94th NY, the two

senior colonels of the 1st Brigade, were also away, wounded and

captured.

Coulter

transfered his regiment with him, and ordered Lt. Abner Small, the

adjutant of the 16th Maine, to his staff.

After the

war, Major Small, authored the 16th Maine regimental history,

and his own personal memoirs, 'The

Road to Richmond.' The latter was written for

his family but was published post-humously in 1939 by his son Harold

A. Small, one time editor of the University of California

Press.

The fortunes of the 16th Maine were intertwined with the 13th

Mass., and Major Small's expressive writing adds

detail left out by soldiers of the 13th. His depictions of

Colonel Coulter are priceless.

The following

narrative borrows from both of Major Small's writings,

beginning with

an excerpt from 'The

Road to Richmond.'

July 2d our corps had a new commander, General

Newton,

whom we didn’t know; an old regular, rather quiet in his bearing, and

with a large, kindly face and level eyes. Doubleday had

earned

the command, but was returned to his division.

Towards noon, we were

moved to the right and placed in support of batteries on Cemetery

Hill. All around our front and along the ridge beyond our

left

there was a continuous stir of preparation for more fighting. Colonel

Coulter acquainted himself with the condition of the brigade, and made

some staff appointments. I had a change of duty by the

following

order:

The following order was announced: —

General Order, No. 44.

Adjutant A.R. Small, 16th Me. Vols., is hereby detailed as

Acting Assistant Adjutant-General of this Brigade… He will be

obeyed and respected accordingly.

By command of Col. R. Coulter,

Com’dg Brigade.

Until mid-afternoon the day was not noisy; only

the

movements of troops near by, the occasional bark of a gun on the hill,

and father away the scattered rattle of skirmish fire, disturbed the

sultry quiet. Our men caught snatches of rest.

About

half-past three some rebel guns east of the town opened fire against

batteries not far from us, which replied, and the quarrel was kept up

through more than an hour. At the same time we began to hear

other cannonading away to our left, and towards evening we heard from

that direction the confused uproar of battle.

About sundown our brigade was hurried to the scene

of

action. Our way was swept by rebel artillery fire. As we

passed

the little house on the Taneytown road that was Meade’s head-quarters,

a shell burst in our regiment and severely wounded Lieutenant Beecher

and seven men.

General

Meade's Head-quarters, the Leister House on the Taneytown Road, —

where the shell exploded as the 16th Maine passed by.

Note

the dead horses in the road. The soldiers of Coulter's

Brigade came down this road, toward the viewer.

David Sloss, William R. Warner & Charles

Davis, Jr. of the

'13th Mass.'

mention the incident of the shell landing in the ranks of the 16th

Maine.

The brigade dashed on at the double

quick.

We heard the shouted command, “By the right flank-march!” In

line

of battle we hurried on through smoke, over rough ground, into the

uproar, just as the rebels were driven back. The rush of grey

had

swept up through a battery. If I remember rightly, two of the

guns were brought off by our men. The enemy did not renew the

attack. We were marched back to our position on the right.

After dark, I should say about nine o’clock, we

were

moved down the front of the hill, under our batteries and near the

town. Rebel sharpshooters were firing from the windows of

houses near

by. A stone wall offered some protection to our brigade, and

the men

lay on their arms until morning.1

Colonel Coulter established his quarters in an “A”

tent,

pitched by his

orders on the brow of the hill at the left of cemetery, in the edge of

a grove, just in rear of the brigade’s last position on the second day,

and planted in clear view of the rebels the brigade flag.

From

this point I took in nearly the whole line from the cemetery to Weed’s

Hill. The position of the national line of skirmishers was

clearly defined by a streak of curling smoke that lazily faced into

thin vapor. The sky was clear, and a quiet aspect pervaded

everything --‘t was a moment of rest before a

battle. The

lazy attitude of men and horses, the apparent indifference of all the

army appointments, as the sun went down, afforded but slight indication

to a looker-on of the terrible storm gathering for the morrow – a day

ever memorable in American history. During the night eighty

thousand

men concentrated behind the rocky ridge in Lee’s front.2

NOTES

1. "The Road to Richmond", by Major Abner R.

Small, University of California Press, 1939; p. 103-104.

2.

"The 16th Maine Regiment in the War of the Rebellion

1861-1865", By Major A. R. Small, B. Thurston &

Company, Portland, Maine, 1886; p. 121.

General Lee's Statue at

Night, Gettysburg. Photo by Buddy Secor.

Return

to Table of Contents

The '13th

Mass' on July 2nd

When writing

the Gettysburg narrative for the regiment in his history of the 13th

Mass., Charles Davis, Jr. borrowed heavily from the journal of William

R. Warner which was at his disposal. The two accounts

overlap, but both gentleman add personal anecdotes. Both

mention the shell which exploded among the remnant of the 16th Maine

during the hurried march to support the Union left in the early

evening. Davis made a poignant comment on the affair but

mistakingly inserted it into his entry for July 3rd. I have

included it here in its proper place.

I found both

accounts vague as to getting specific information as to what the

regiment did on July 2nd. The essay which follows these

entries titled, "So where exactly were they on July 2nd?" was the

result of my research to learn more.

Diary

of Lieutenant William R. Warner

Once

again I must thank Warner's step descendant Mr. Eric Locher for

allowing me to share this excerpt from Warner's unpublished manuscript.

Also - thanks to Buddy Secor for the incredible photographs.

His work can be seen at 'Ninja Pix"

on facebook & instagram.

Very early in the

morning, in the gray dawn, we were all

astir – Fresh troops were coming into position, and we felt assured

that the

entire Army of Potomac was close at hand.

A party of Officers came toward us, among whom

was Gen Hancock. Some

of our boys were exposing themselves on

top, & other side of the slight breastworks we had thrown up,

and Hancock

called out pleasantly, “Keep down, boys that is the way with you

Massachusetts

boys – too much damned curiosity – Keep down.”

The day passed, without

any active Movements on the part of

our Brigade & Division which was so reduced in numbers, it was

only

available as supports to other troops.

When Sickles was pushed back at nightfall, Robinson’s Division was

hurridly sent to the left, as re-inforcements.

Before we reached there, it had grown so dark, that the smoke &

fire

of the rebel artillery lighted up like sheets of flame —

Marching Brigade front, a

shell struck in

line of adjoining Regiment where the men had swayed closely together,

knocking

over I should think nearly a dozen men. How many were

killed, we knew not. We passed a Battery

on our right from which nearly every horse and at least half the men

were gone

– The tide had turned, and the rebel infantry had gone back.

Our lines were being re-formed and later in

evening, Our Division returned again to Cemetery Hill, where Hay’s

Louisiana

Brigade had attempted To take possession

of Ricketts & Wiedrick’s Batteries by an Evening Charge.

The Movement down to the

left in afternoon of 2nd

day, when we came under direct fire was a time, that tried men’s

courage— There

was no personal bravado, no cheers of excellent troops, it was looking

possible

death in the face & each man recognizing to himself, his own

helplessness

to avoid it and fate pushing him on quietly to take it all.

On Evening of 2nd

day, after Sickles repulse, as

we passed the Artillery which was being dragged from the field by men,

the

horses being killed, we passed several men drawing off by the legs,

what

appeared to be the headless body of an Officer. —

Colonel Coulter of 11th

Penn.

was in his best

fighting mood. It

was a weird scene —

darkness was fast settling down, and when a Cannon of the Enemy was

fired, it

showed a flame instead of smoke, until it seemed we could almost look

into

their Muzzles.

Col Coulter was shouting, “Let us Charge —

Let us give them Cold Steel by Moonlight.”

(photo by

Buddy Secor).

The following is from "Three Years

in the Army, The story of the Thirteenth

Massachusetts Volunteers from July 16, 1861 to August 1, 1864."

by Charles E. Davis Jr. Boston, Estes and Lauriat, 1894. p. 233-234.

Thursday, July 2.

By reason

of our hard

work of yesterday, we were to-day held

in reserve. It

often happens that this

kind of duty turns out to be more arduous than being stationed in line

of

battle, inasmuch as you may be called upon to march to any point that

needs

strengthening, as it happened with us on this particular day.

Upon

waking in the morning, we found everything astir with

excitement and preparation. Thousands

of

troops had gathered during the night, presenting a formidable

appearance in the

gray morning light. As

we were gazing about,

a party of officers were seen approaching, among whom was General

Hancock. Some of

the boys, regardless of danger, were

exposing themselves on top and at the sides of the earthworks that we

built

last night, when, in a mild, pleasant voice, General Hancock said,

“Keep down,

boys; that is the way with you Massachusetts boys – too much damd

curiosity;

keep down !’

In

the afternoon, as Sickles’ corps was being

pushed back at the peach orchard, our division was sent hurriedly to

his

support.

While

we were formed in line, marching brigade

front, a shell exploded in the midst of an adjoining regiment, knocking

over a

dozen men.

Historian Davis

commented on the incident of the shell exploding amidst the 16th Maine

troops in his narrative, but he mistakenly assigned the event to July

3rd; the wrong date. Here is what he wrote:

"During

the movement, an incident happened to show the hard luck that followed

a

gallant regiment. The Sixteenth Maine, during the first day’s

fight, was assigned the very difficult duty of holding on and delaying,

if possible, the advance of the enemy until the rest of the division

could get to the rear; and it did its work bravely and with great

credit to itself, its colonel and most of the men being take prisoners

in the endeavor. The remnant of about twenty men that escaped

were just ahead of us as we double-quicked along the ridge.

Suddenly a Whitworth shell from one of the enemy’s batteries exploded

in

their midst, and it seemed to us, as we hurried on over the mangled

bodies, that every man must have been killed. Our entire

division

at this time, consisting of eleven regiments, numbered only about nine

hundred men, and we felt sorry enough to see the remnant of this

excellent regiment so completely wiped out.

While these sights

were such as are commonly observed on all battlefields, they seemed

more hideous than any seen before, even to those familiar with such

scenes."

As the rebel infantry were

being driven back

at the moment of our arrival, our services became unnecessary, and

later in the

evening we returned to Cemetery Hill to support Ricketts’and

Wiedricks’s batteries,

which were being charged by the Louisiana Tigers. We were

thrown

in the

front

of these guns, with orders to hug the ground as closely as possible

while the

batteries fired over us. There

is no

more trying situation for a soldier than to be lying down in front of a

battery. He is only

a few yards in front

of the guns, and the concussion from each discharge seems to travel up

his

spinal column to the top of his head. The noise is terrible and

appalling. The

testimony of men who have undergone such

an experience is, that they endure more mental suffering than when

standing in

line of battle. You

are being constantly

pelted with the packings, as they become dislodged from the shells when

they

leave the muzzle of the gun. These

pieces are not dangerous though they often make an uncomfortable

contusion, the

size of a walnut, if they hit you. If a piece strikes you on

the

head

you will

think, as the boy did, that “you might as well be killed as scared to

death.”

A.R. Waud Sketch titled,

"Attack of the Louisiana Tigers on a Battery of the 11th Corps."

All the

afternoon we listened to the sound of battle at

our right on Culp’s Hill, dreading defeat and another

retreat. It

made us sick at heart

to think of what might

occur in such an event, and glad we were when night came and put a

temporary

stop to the fighting. Evidently

we had

not held our own at this point.*

So far as

exposure to danger is concerned, our division

may be said to have had very good luck.

There was hard fighting, at different points

all day, and even into the

night, without apparently any advantage having been gained by the Union

army. During our

absence to the left of

the line, where we were sent to help the Third Corps, there was hard

fighting

at Cemetery Hill, and by the time we got back the fighting was

practically over

at that point; so we escaped loss in both instances.

*NOTE: I find this

comment very confusing as far as the narrative goes. Although

there was an afternoon artillery duel between Union artillery on East

Cemetery Hill and part of a battery posted on Culp's Hill, with

Confederate artillery on Benner's Hill, the Confederate

infantry assault did not begin until the evening, and the '13th Mass'

were at another part of the field which is quite distant. I

believe Davis was trying to relate the emotions included in the source

material from William R. Warner and E. F. Rollins into his narrative.

The Warner Manuscript jumps around in its commentary so I can

see how Davis became unintentionally confused. See the

following essay for more information.

Return

to Top of Page

So,

Where exactly

Were They On Day 2?

View

looking west towards the enemy; from the position held by part of

Robinson's Division, the night of July 1st, through morning, July 2nd.

The Emittsburg Road is in the middle-ground.

Having read the

entry as written above, in the regimental history, along

with William R. Warner's journal, I was still very

confused about what the regiment did on July 2nd. While

puzzling over this question I was fortunate to meet some very

knowledgable historians from Gettysburg, who offered to walk the field

with me to try and sort things out. A few weeks

later we did this.

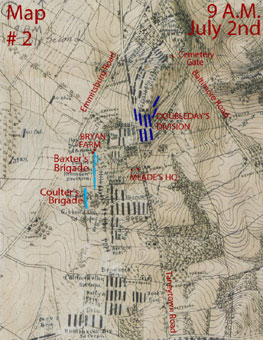

I am

grateful to Bob George who printed out these cropped versions of the

John B. Bachelder maps of the battle for my reference.

And, to Steven Floyd,

an expert on the Gettysburg Monuments, and Craig Berkeley, who provided

information about the town at the time of the battle. We all

walked over the

ground together, and shared our knowlege of the battle. The

following essay is the result of all this study, and specifically shows

where and what the regiment did on July 2nd. An unintended

result of the research, is that it provides insight on General George

Gordon Meade's laudable command of the army during several extreme

emergencies on the 2nd day of battle. Click on any

map to view it larger.

So

far, we've heard from Adjutant Abner Small, of Colonel Coulter's staff,

and William R. Warner and Charles E. Davis, Jr., of the 13th Mass.,

regarding the

movements of Coulter's Brigade on July 2nd. But where was

Coulter's Brigade, and the 13th Mass. Regiment

actually positioned on the battle-field this day?

The soldiers used phrases like, 'we moved to the

right

near

the cemetery,' or,'we moved to the left as reinforcements.'

To

add to the confusion, Warner jumped around in his journal when he wrote

his entries for day 2, and Davis, who was not at the battle, followed

the same pattern in his narrative. The soldiers on

the field

made note of the impressions that were important to them, and these

small shifts in position were routine.

The

following essay is presented to sort things out, and show that these

troops

were much more active than they suggested. The hourly battle

maps

by Gettysburg historian John B. Bachelder are used as

reference. Bachelder made a life-long study of the battle,

and began gathering up information about troop positions by

interviewing participants as soon after the battle as he could.

He spent time in the camps of the Army during the winter of

1863-64. According to these hourly maps, Coulter's brigade,

(Paul's) held

five positions on July 2.

Starting with the position the regiment took up

after their retreat to Cemetery Hill, the evening of July 1st, we see

them in line just south of the Bryan Farm, extending south on

Cemetery Ridge to the angle in the Union line.

They were probably near the Bryan Farm where, as they wrote,

"Here we saw the division color-berarer standing alone.

Some of the boys then took the flag, and waving it in turn, shouting

and swinging their caps, soon succeeded in establishing the division

headquarters. While this was going on, others of the boys

went

actively to work bringing rails or digging, until we had a

well-formed

rifle-pit in readiness to again meet the enemy's attack; but we

remained un-disturbed during the night."

Early next morning, they woke up to General

Hancock riding the lines. Hancock's

2nd Corps moved into

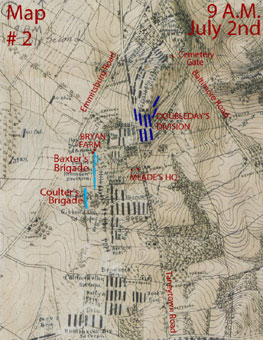

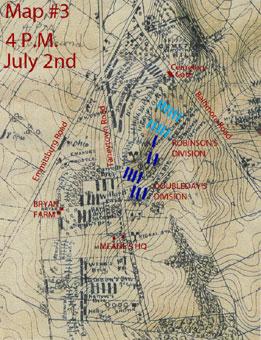

their position, making it much stronger. Map #2

shows

Coulter's and Baxter's brigades still in position just south of the

Bryan Farm at 9 a.m., July 2nd. But now, they are surrounded

by troops

and

artillery of the 2nd Corps. Fortunately, things still

remained

quiet throughout the morning, giving the troops time to form their

lines un-molested. When the 2nd Corps was ready, Robinson's

Division moved

a

little to the east to join General Doubleday's Division, in reserve.

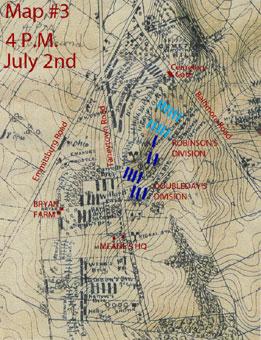

Here, these two First Corps Divisions remained at

rest behind troops

and batteries of the Eleventh Corps on Cemetery Hill.

(Wadsworth's

1st Division of the First Corps had taken a position on Culp's Hill,

farther to the east, and remained there throughout the battle.)

Map

#3 shows Doubleday and Robinson in reserve. The time is 4

p.m.

in

the afternoon, which marks the beginning of an artillery duel between

Union guns on East Cemetery Hill, and Confederate artillery