The Battle of Fredericksburg; Dec. 11th-15th, 1862

Part 1; Summary & Soldiers' Accounts

"The Bombardment of Fredericksburg, December 11th, 1862" by R. F. Zogbaum.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- President Lincoln's Plan

- Summary of the 13th Massachusetts' Actions in the Battle

- Letter from the Battlefield; Charles Adams, Co. A

- George Jepson's Reminiscence of the Battle

- Reminiscence of David Sloss, Co. B

- Mannsfield; The Bernard House

- Austin Stearns Memoirs

Introduction

The late arrival of pontoons necessary for the Union Army to cross the Rappahannock River allowed time for the Confederate army to concentrate on the hills outside Fredericksburg, Va and marshal a formidable defensive line. Despite this, Gen. Burnside stuck to his plans to cross the river opposite the town and attack the Rebel army. To slow them down, a brigade of Mississipians fired at the Union engineers from houses in town, and kept the Yankee bridge builders at bay for a better part of the day, Dec. 11th. An artillery bombardment could not disperse the Confederates, but it harmed the town. Eventually a Union detachment had to cross the river in boats under fire, and storm the town to drive away the deadly determined Southerners. Frustrated Yankee troops shamefully looted the town in the evening as they filed in from across the river. The sacking of Fredericksburg is forever a black spot on the record of the Army of the Potomac. The rest of the Army crossed the River on the 12th while Gen. Burnside planned his attacks. His “Left Grand Division” commanded by General William B. Franklin, was to lead the assault against the Confederate lines posted on a ridge outside town. “Franklin and other generals proposed having the First and Sixth Corps launch a massive assault against Lee's right flank.” 1 That afternoon, Burnside promised he'd get orders to Gen. Franklin, then rode away to visit other generals. Franklin waited up much of the night for instructions but the orders never came. His aid delivered the promised orders at 7:30 A.M. December 13th, — and they were vague. (See discussion in the “Commentary” section on page 3). Instead of a massive attack, General Franklin chose to interpret his orders conservatively, and ordered two divisions to probe the Confederate lines in his front. General George Meade whose division led one of the attacks bristled at the prospect of an un-supported attack against a strong Confederate line. “He complained to Franklin that attacking with a single division would simply repeat the mistakes of Antietam, where piecemeal assaults had yielded little but heavy casualties. His division could take the heights Meade believed, but could not hold them. Typically laconic, Frankiln replied that these were Burnside's orders and they would be obeyed.” 2 General Meade was right. Elements of his division broke through the Rebel defenses but without supports they were forced to fall back sustaining heavy casualties. The same happened with General John Gibbon's Division, the other division to attack the Rebel defenses on Franklin's half of the battlefield. According to Burnside's plan, while the troops on his left were rolling up the Confederate right flank, a co-ordinated Union assault would begin against the Confederate left flank. Instead, an inexcusable slaughter ensued. Seven repeated charges melted away against Confederate General Lee's impregnable position anchored at Marye's Heights.

“Union soldiers had to leave the city, descend into a valley bisected by a water-filled canal ditch, and ascend an open slope of 400 yards to reach the base of the heights. Artillery atop Marye's Heights and nearby elevations would thoroughly blanket the Federal approach. “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it,” boasted a Confederate cannoneer.3 “Soldiers could hardly forget the sights — hands, legs, arms and heads shot off and bodies mangled beyond recognition — reminding one Rebel of hog butchering time back home.” 4 [Pictured are troops of Kershaw's and Cobb's Confederate Brigades behind the stonewall at the base of Marye's Heights, Battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13, 1862.] For some reason, General Burnside at his headquarters across the river, thought General Franklin's attack was succeeding. Expecting to hear that the Confederate right had collapsed, he kept up the attacks in front of Marye's Heights on the Confederate left. The futile attacks continued until darkness fell over the field. “Of the 12,600 Federal soldiers killed wounded or missing, almost two-thirds fell in front of the stone wall.” 5

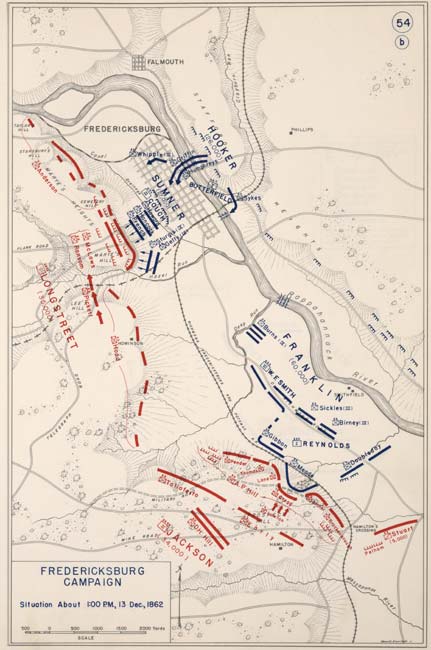

On the morning of December 14th, Burnside's generals talked him out of resuming the attacks against Marye's Heights. The two sides endured an anxiety ridden 'quiet day' while the Union generals decided their next move. The uneasiness continued on the 15th. At night on the 15th, and through the early morning hours of the 16th, the massive Federal Army quietly slipped back across the Rappahannock River. Before the Confederates knew what happened, the pontoon bridges were taken up and the Army of the Potomac was safe on the other side."Lucky 13" The “13th Mass.” were extremely lucky at Fredericksburg. They did not participate in any of the iconic dramas for which the battle is known. Their river crossing at the lower bridge was un-opposed. They were not in the town, so did not participate in the wild looting. They were thrown out as skirmishers for the Left Grand Division, Dec. 12th, and remained in that capacity for two days. The map at right depicts the lines of battle about 1 p.m. Dec. 13th. General John Gibbon's Division was chosen to support Meade's attack against the Confederate right. When the charge began the skirmishers of the 13th Mass. regiment were out of ammunition. The advancing troops passed over them and they fell back to the rear, as ordered, to replenish their cartridge boxes. Casualties for the regiment were light. Indeed when private John B. Noyes returned to the regiment in late January, 1863, he noted that “Our men talk more of the unsuccessful move preceding Burnside's withdrawal from the Army [The 'Mud March,' Jan. 20th - 23rd, 1863] than of the Fredericksburg fight.” 6 The part played by the 13th Mass. regiment was straight-forward as the narratives on this page prove. There is a lot of repetition but each account adds color to the overall picture. The summary by Charles E. Davis, Jr., describes the horror of laying in front of active field artillery; George Jepson finds humor in a series of stories from the skirmish line; Sergeant Austin Stearns gives a good account of the banter between Reb and Yank, and the duties of the Color Guard. On page 2, more vivid material details the experiences of the regiment. Private Bourne Spooner and others, provide names and details of those killed and some of the wounded. Sergt. John S. Fay gives a riveting description of the retreat. Don't miss the vivid letters of

private Charles F. Adams, (Co. A)

and Corporal George Henry Hill, (Co. B). There are

also rare company reports by First Lieutenants John Foley,

(Company

G) and Morton Tower, (Company B) in the Official Reports

section on page 3, and the story of Charles J. Taylor, one of the 4 men

killed at the battle. FOOTNOTES: Picture credits: All images are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: General Burnside from "The Photographic History of the Civil War" Francis Trevelyan Miller, New York, The Review of Reviews, 1911; David Sloss, from his descendant, Mr. Jim Perry; George Emerson, from collector Scott Hann; Corporal George Henry Hill from his descendant, Carol Robbins, sent by Alan Arnold; Charles F. Adams, from James Lowell descendant, Tim Sewell; Capt. James A. Hall, from Army Heritage Education Center, Digital Image database, Mass. MOLLUS Collection; William Blanchard from artifacts dealer, Steve Meadows; "Deploying the Colors" by Austin Stearns, from "Three Years in Company K" Associated University Press, 1976; Barnard House & Franklin's Corps Recrossing the River from sonofthesouth.net; Special thanks to my wife Susan who turned a poor photocopy from the Massachusetts Historical Society into a beautiful portrait of N.M. Putnam. She also photographed the battlefield when I visited in February, 2012. The illustration "Americans but Brothers" is by J. S. Barrows, from Carleton's "Stories of Our Soldiers" The Boston Journal Newspaper Company, 1893. ALL IMAGES have been EDITED in PHOTOSHOP. President Lincoln's PlanThe following is from Abraham Lincoln; Speeches and Writings, 1859 - 1865; The Library of America. I have added a couple paragraph breaks for easier reading.President Lincoln was worried about the Army crossing the Rappahannock River directly in front of the enemy. Steamer Baltimore Major General Halleck I have just had a long conference with Gen. Burnside. He believes that Gen. Lees whole army, or nearly the whole of it is in front of him, at and near Fredericksburg. Gen. B. says he could take into battle now any day, about, one hundred and ten thousand men, that his army is in good spirit, good condition, good moral, and that in all respects he is satisfied with officers and men; that he does not want more men with him, because he could not handle them to advantage; that he thinks he can cross the river in face of the enemy and drive him away, but that, to use his own expression, it is somewhat risky. I wish the case to stand more favorable than this in two respects. First, I wish his crossing of the river to be nearly free from risk; and secondly, I wish the enemy to be prevented from falling back, accumulating strength as he goes, into his intrenchments at Richmond. I therefore propose that Gen. B. shall not move immediately; that we accumulate a force on the South bank of the Rappahannock — at, say, Port-Royal, under protection of one or two gun-boats, as nearly up to twenty-five thousand strong as we can. At the same time another force of about the same strength as high up the Pamunkey, as can be protected by gunboats. These being ready, let all three forces move simultaneously, Gen. B.’s force in it’s attempt to cross the river, the Rappahanock force moving directly up the South side of the river to his assistance, and ready, if found admissible, to deflect off to the turnpike bridge over the Mattapony in the direction of Richmond. The Pamunkey force to move as rapidly as possible up the North side of the Pamunkey, holding all the bridges, and especially the turnpike bridge immediately North of Hanover C.H; hurry North, and seize and hold the Mattapony bridge before mentioned, and also, if possible, press higher up the streams and destroy the railroad bridges. Then, if Gen. B. succeeds in driving the enemy from Fredericksburg, he the enemy no longer has the road to Richmond, but we have it and can march into the city. Or, possibly, having forced the enemy from his line, we could move upon, and destroy his army. Gen. B.’s main army would have the same line of supply and retreat as he has now provided; the Rappahanock force would have that river for supply, and gun-boats to fall back upon; and the Pamunkey force would have that river for supply, and a line between the two rivers — Pamunkey & Mattapony — along which to fall back upon it’s gun-boats. I think the plan promises the best results, with the least hazzard, of any now conceiveable. Note — The above plan, proposed by me, was rejected by Gen. Halleck & Gen. Burnside, on the ground that we could not raise and put in position, the Pamunkey force without too much waste of time. Summary of the 13th Massachusetts' Actions in the BattleJames Lorenzo Bowen The following is an excerpt from James Lorenzo Bowen's work, “Massachusetts in the War, 1861-1865.” Springfield, Mass., 1889.

Franklin's Crossing over the Rappahannock River The Thirteenth with their division crossed the Rappahannock at Franklin's bridges, some three miles below the city of Fredericksburg, early on the morning of the 12th, moving to the left near the river, where the regiment deployed as skirmishers, advanced to the Richmond stage road, and remained during the night which followed and next morning till the opening of the battle. The skirmish line moved forward and engaged the enemy, keeping up a sharp fire till the division in line of battle advanced and passed to the front. The eight companies of the Thirteenth which had been on the skirmish line for 24 hours then rallied on the two in reserve and the regiment was sent to the rear for a fresh supply of ammunition. Before it was ready to resume active operations at the front the fight there had practically ceased; General Meade's Division, the Third, had made its magnificent attack, supported by the Second (Gibbon's), and the shattered forces had fallen back with heavy loss. General Gibbon was wounded and General Taylor assumed command of the division, placing the Third Brigade in the hands of Colonel Leonard. Position was taken near the Richmond road, where the brigade remained during the night. It staid in that vicinity, in fact, till the withdrawal of the Federal troops from that side of the river, no further fighting of consequence taking place. Recrossing on the night of the 15th, the regiment at first bivouacked some two miles from the river, but on the 19th it moved to the vicinity of Fletcher's Chapel into a more permanent camp. The loss of the Thirteenth during the battle of Fredericksburg was but three killed and 11 wounded, its service on the skirmish line having saved it from the severe loss which had met the regiments forming the line of battle. At the close of the engagement, though the largest regiment in the brigade in numbers, it had but 314 present for duty. The Four Men Killed Though 3 men were officially reported killed after the battle, another, died on December 19th. The four men killed from the

regiment are, George E. Bigelow, Company C, died of wounds Dec. 19,

1862; Charles Armstrong, Company D, Charles J.

Taylor, Company D; and Edmond H. Kendall, Company D. Details

about all of their deaths can be found on this site. Armstrong,

Taylor and Kendall on page 2 of this section; Taylor & Armstrong

are reprised on page 3. George E. Bigelow

gets a special page to himself on the web page titled “Year End;

1862.” Kendall, Bigelow and Taylor all had wives and

children. I am not sure about Armstrong. Unfortunately, I do not have images of any of these men. Narrative from the Regimental History by Charles E. Davis, Jr. The following excerpt is from“Three Years in the Army: The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers.” Estes & Lauriat, Boston, MA; 1894. Thursday,

Dec.

11. “Fredericksburg The Night of the 11th” sketched by A. R. Waud Friday, December

12. In crossing a pontoon bridge men are cautioned not to keep step. A pontoon bridge in not a very substantial structure, therefore any regularity of step would tend to sway it from its moorings. We then marched along the bank of the river in an easterly direction about half a mile, and halted; where upon the colonel was asked by General Gibbon if he could deploy his whole regiment as skrimishers at once, and being promptly answered that he could, he was directed to do so. The ground in front of us was a flat un-obstructed plain of considerable extent, where every man of the regiment could be seen as he deployed. On our right was a Vermont regiment and on our left a Pennsylvania regiment, also deployed as skirmishers. These three regiments constituted the skirmish line of the Left Grand Division, and it advanced firing at will and slowly driving back the rebel skirmishers toward their main body. After dark we arrived at the Bowling Green road, which, being a sunken road, afforded us protection from the enemy’s fire. Here we remained all night as a picket guard for the First Corps. The regiment was divided into three reliefs, each of which was sent out in turn some distance beyond the road and within talking distance of the rebel pickets.

The Slaughter Pen Farm, Fredericksburg National Battlefield Park. This land was aquired by the park in 2006. The view is beyond the Bowling Green Road, looking towards Jackson's Confederate line (the base of the ridge in the background). Meade's Division was on the left, Gibbon's Division, to the right. This view mostly encompasses Gibbon's front. During the night the enemy set fire to some buildings near by, illuminating a considerable extent of country, while hundreds of men of both armies swarmed to the fences to watch and enjoy the sight. All night long we could plainly hear the sound of axes in the enemy’s camp, which we subsequently learned were being used in the preparation of obstructions against our advance in the morning.

While we were deployed as skirmishers a captain of one of the companies observed a man who, up to this time, had always failed to be present on any important occasion, endeavoring to escape to the rear, when he called out in a loud voice, “C — , get into your place, and if you see a ‘reb,’ SHOOT HIM!” — “Shall I shoot right at him ?” whined C. A few minutes later he disappeared and was not seen again until the “surgeon’s call” was established in camp, some days later. An incident happened shortly after our skirmish line returned to the Bowling Green road that afforded us a good deal of amusement. The boys had just started fires for coffee when a young officer, whose new uniform suggested recent appointment, approached and with arbitrary voice ordered the fires to be put out, at which the colonel exhibited an asperity of temper that surprised us, who had never seen him except with a perfectly calm demeanor. Our experience on the picket line had taught us how to build fires without attracting the attention of the enemy, and we liked it not that a young fledgling should interfere with our plans for hot coffee. The colonel’s remarks were quite sufficient for our guidance, so we had our fires and our coffee too, while the officer went off about his business. Another incident occurred to add interest to the occasion. Our pickets, as already stated, were so near to those of the enemy that conversation was easily carried on. One of the rebel pickets was invited to come over and make a call, though the invitation may have appeared to him very much like the spider to the fly. After some hesitation and the promise that he would be allowed to return he dropped his gun and came into our line and was escorted to one of the fires, where he was cordially entertained with coffee and hardtack, probably to his great delight, inasmuch as coffee and hardtack were not so abundant in the South as to allow a distribution of it as an army ration. “If thine enemy hunger, feed him; overcome him with good.” Fill him with lead, good lead, was what we tried to do most of the time. After he had enjoyed our hospitality as long as he dared he returned.

On the following day, while we were halted at the Bernard house, who should be brought in a prisoner but this same man, who was greeted with shouts of welcome and friendly shakings of the hand. Some years after, one of the regiment, while travelling in Ohio, became acquainted with a man tarrying at the same hotel. After supper the two sat down to talk, and very soon the conversation drifted to the war, when it was discovered that each had served in the army, though on opposite sides. The Southerner, learning that his new-found acquaintance was a member of the Thirteenth, remarked that it was a rather singular coincidence, for “I was entertained by that regiment once at Fredericksburg, and a right smart lot of fellows they were;” and then he told what has been in substance, related here. As our comrade was present at that battle, and a member of the company that did the entertaining, he was perfectly familiar with the facts, whereupon mutual expressions of pleasure followed and an adjournment for “cold tea.” Saturday

Dec. 13 “If your officer’s dead and

the sergeants look white, Our

batteries were speedily brought into position, and began shelling the

woods, while the enemy’s guns, in turn, opened upon us. We

were

between two fires, and the greatest caution was necessary to prevent a

needless loss of life. Very soon we were ordered to lie down

as

close as possible to the earth in the soft clay, rolling over on our

backs to load our guns. We were now engaged in the very

important

service of preventing the enemy from picking off the men of Hall’s

Second Maine Battery, then engaged in shelling the enemy, from a

position slightly elevated in our rear. In order that this

battery might do as effective work as possible, it was

ordered to

point its guns so as to clear us by one foot. Pictured at right is Capt. James Abram Hall, 2nd Battery, Maine Light Artillery. About one o’clock a general advance was ordered. Those on the left moved first,* then came our brigade. As skirmishers, we advanced in front of our division until the firing became so rapid that we were not only of no advantage, but interfered with the firing of our troops, so we were ordered to lie close to the ground while our troops passed over us. Toward night we were withdrawn to the Bernard house, which had been turned into a hospital, and replenished our empty boxes with ammunition. Our losses were three men killed, one officer and twelve men wounded, making a total of sixteen. As we were withdrawn from the skirmish line to the rear our appearance excited a good deal of mirth among the old soldiers, who knew too well what rolling round in the mud meant, for we were literally covered with the clayey soil that stuck to our clothing like glue. We had had a pretty hard time of it, as after each time we fired, we turned over on our backs to reload our guns. Hours of this work had told on our appearance as well as our tempers, so that when some of the men of a new regiment asked us why we didn't stand up like men and fight, instead of lying down, we felt very much like continuing the fight in our own lines, to relieve the irritation we were suffering. *Meade's Division is on their left and moved first. So far this month we had suffered from the cold and from frequent show-storms, but this night (the 13th) was bitter cold, and the suffering of the wounded must have been very great. Commentary by Davis on Skirmish Duty To be thrown out as skirmishers in front of a line of battle, the observed of all observers, seems more dangerous than when touching elbows with your comrades in close order, but as a matter of fact it is not generally attended wtih so great loss. It is a duty requiring, when well done, nerve and coolness on the part of both officers and men. You are at liberty to protect yourself by any means that may be afforded, such as inequalities of the ground, a bush, a tree, a stump, or anything else that you may run across as you advance. The fire which you receive is usually from the enemy's skirmishers, and is less effective than when directed toward an unbroken line. You are supposed to load, fire, and advance with as near perfect coolness and order as you can command, becaue on that depends the amount of execution you are able to perform. It is no place for skulkers, as every man is in plain sight, where his every movement is watched with the closest scrutiny. As soon as the skirmish line of the enemy is driven back, the main line advances, and very soon the battle begins in earnest; whereupon the skirmishers form in close order and advance with the rest of the line, except in cases, like the one just related, when it was necessary to replenish the boxes with ammunition. We had acquired a good deal of proficiency by constant drilling for many months in this particular branch of the tactics, long before we were called upon to put our knowledge into practice. We growled a good deal at the colonel in the early days of our service for his persistence, but we had already realized how valuable a lesson he had taught us. There were occasions, as will be seen later on, when this kind of service was very dangerous; but, as a whole, our losses on the skirmish line were lighter than some other regiments, and we think it is not unfair to attribute the fact to the thorough instruction we had received. It was an old story, — the oftener a man does a thing, the better he can do it. Letter from the Battlefield; Charles Adams, Co. A

Charles Follen Adams of Company A, gained notoriety after the war for his series of humorous poems titled, “Little Jacob Strauss,” or “Leedle Jawcob Strauss,” written in German Dialect and published in various incarnations throughout the late 1800's. Several of his war time letters are in the collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. He joined the regiment as a recruit in August, 1862. Charles Follen Adams to Sister Hannah, 14 December, 1862; Charles Follen Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Used with permission. Near

Fredericksburg Va. Dear Sister Hannah, I suppose that you have received the news of the taking of Fredericksburg before this mail came off the 14th. We were out round where we could see the fun though we took no active part in the fight as it was done mostly by artillery. I say we as Walter joined us to day & is now with us. Day before yesterday we crossed the Rappahannock river on a pontoon bridge in pursuit of the Rebs & our Co & one other were deployed as skirmishers & as we were the head regiment of the division it brought us right in front of the whole army corps. We came late in the afternoon to the woods where they the Rebs made a stance & had thrown out their skirmishers & consequently we stopped just in sight of them to inform our troops of their whereabouts. We were on picket guard that night & could hear their voices in the woods & they were making breastworks all night. Yesterday we had a rousing battle. It commenced early in the morning p. 2 lasted all day & still continues. We are now supporting a battery not being engaged at this moment. We can hear the firing of the skirmishers just over the hill but are not allowed to show our heads where we can see what is going on. I thought I would just write a few lines though I don’t know when I can send it. It was an awful day yesterday I can tell you the whole rebel army or at least a large part of it is supposed to be concentrated here. We have thousands of troops in the field & reinforcements coming in all the time. I don’t know the result of yesterdays fighting but there must have been thousands killed on both sides it was one continual roar of artillery and musketry till late at night. We advanced to the front & engaged the rebels advance troops while our line of battle formed, when we laid low & allowed them to pass over us as we were ordered back as a reserve. We went back & got more ammunition & then went back to our position in the reserve. We laid on the field all night with our equipments on & this morning took our present p. 3 position supporting a battery & there is a fair show for another engagement immediately. One poor fellow is just being carried by me as I am writing this probably a skirmisher as they are now blazing away good from over the hill. I hear that A. P. Hill commands the rebel forces in our front. On our side, Hooker has the center, Sumner the right & Franklin the left of our army. Our division is on the extreme left & commanded by Gen Taylor as Gen Gibbons was wounded yesterday. The rebs fought like tigers, in the woods as usual, & their sharpshooters in the trees trying to pick us off, and they came pretty near it as I could almost feel the wind of their bullets they came so near to my head but luckily none of our Co were wounded - - - There seems to be a movement among our troops & another battery is coming up I will close for tonight and write in the morning aps. Monday morning C.F.A. — Walter says he will write soon Got the box all safe *Walter is Walter S. Fowler, fellow recruit of Company A, he was wounded at Antietam. George Jepson's Reminiscence of the BattleThe regimental roster states, Boston clerk, George E. Jepson, age 20, mustered into Company A as a private, at Fort Independence, July 29, 1861. He served 3 years with the regiment. In January, 1863 he was detailed at headquarters. His ancestors were Revolutionary War soldiers, and he was proud of this heritage and his military service. Many of Jepson's articles appeared in the pages of the 13th Regiment Circulars. This following article was first published in the Boston Journal, December 13, 1892, for the 30th Anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg. It was reprinted in the 13th Regiment Association Circular #19, Dec. 1906, where I found it. Only a few contemporary references were omitted from the latter publication, — otherwise the text is the same. I have left the later version in tact but restored the original introduction from the newspaper edition, for its interest, and re-inserted the paragraph headings from the same, as it makes easier reading. ORIGINAL INTRODUCTION, BOSTON JOURNAL, December 13, 1892: Thirty years ago to-day came the battle of Fredericksburg. To-day the anniversary is celebrated by the Thirteenth Massachusetts, which fought in that awful scene of carnage. Comrade Jepson, now in the Custom House, who participated in that strife as one of the brave Thirteenth, tells to the Journal readers the story of the battle on the left. The Thirteenth Massachusetts — was formed from the old Fourth Battalion of Rifles — the Old Boston City Guard — which went to Fort Independence in May, 1861. There the Thirteenth Regiment was formed, Captain Samuel H. Leonard of Worcester, now a Brigadier General, was Lieutenant-Colonel. Mr. Jepson enlisted at the beginning, with W. J. Trull, (afterward Colonel). Both were 17 years old, but at that time recruits were required to be at least 20 years old in order to enlist, so they gave their age as 20. The three years before their legal service age was reached they spent in the Thirteenth. They were in eight general engagements. At Fredericksburg the Thirteenth were out as skirmishers. Mr. Jepson is now connected with the Custom House and resides at Watertown. He is a member of the Isaac B. Patten Post 81, Watertown, G.A.R. FREDERICKSBURG - DECEMBER

13, 1862. Forty-four years ago, on the 13th inst., Burnside's army crossed the Rappahannock and brought on the battle of Fredericksburg. Forty-four years ago! What veteran can realize such a lapse of time since the occurrence of an event every incident of which to him who participated in it seems — or so seems to the writer — as fresh and vivid as though it all happened but yesterday! A remarkable battle it was in some features that distinguished it from battles in general.

Days of Anxiety Such were the days of anxious and harassing contemplation during that interval “between the enacting of a dreadful thing and the first motion,” as the Federal army lay along the Stafford and Falmouth Heights waiting for the pontoon trains, which seemingly were never to arrive, and for the word to “forward” from its commander. But at last the pontoons came, the bridges were laid, and on Friday, the 12th of December, the advance of the army proceeded to cross.

Army of the Potomac Crossing the Rappahannock River December 12th 1862. On the Left. My individual reminiscences are confined to the battle on the left, “part of which I was, and all of which I saw. Our regiment — the Thirteenth Massachusetts — had from its organization developed an adaptability for light infantry tactics second to none in the army, its effectiveness due partly to its personnel and largely to the fact that our Colonel, the late Samuel H. Leonard, was one of the best and most indefatigable masters of drill in the service. So we were perfectly at home when, on reaching the southern bank of the river, we were deployed as skirmishers. Not an enemy was at first in sight, and, unlike the experience of our comrades on the right, our crossing was unopposed. As the bugles sounded to advance, the long line of skirmishers stepped briskly forward, until passing over a rising ground the broad plain, whose present smiling and peaceful aspect was in less than twenty-four hours to be disturbed by the horrid din and turmoil of contending armies, burst upon the view. Bisecting this plain could be seen a long row of evergreen trees planted at wide intervals apart on an embankment, indicating one of those beautiful roadways for which this section of the Old Dominion is justly celebrated. It was the famous Bowling Green or Richmond pike.

The buildings in the distance line the Bowling Green Road as it appears today. The '13th Mass' took their position in the road the night of the 12th. From this perspective the regiment advanced to the road from the river, (coming towards the viewer). The hills in the distant background are probably Stafford Heights, across the river, which were lined with Union Heavy Artillery. A Line of Gray. And now, midway of the plain and against this dark background, suddenly emerged into view an opposing line of gray-clad riflemen — the enemy was before us, prepared, apparently, to dispute the right of way. In appearance only, however, for as we advanced the “Johnnies” slowly retreated and we wonderingly saw them clamber over the roadbank and disappear. Thus far not a shot had been fired, which told to each side that the opposing force was composed of veteran troops with nerves too well schooled to lose self-control, forget discipline and become “rattled” at the first sight of an enemy. Undoubtedly each man's pulse was a little quickened, as we drew nearer and nearer, at the seeming certainty that behind the frowning embankment hundreds of death-dealing tubes were levelled at us; but Onward! Onward! sounded the bugles, and on we went, mounted the bank and through the gaps in the cedars beheld our foe slowly retiring behind a ridge of land on the other side of the road and which ran for a long distance parallel with it. Once in the roadway the bugles signaled to halt, and the strain upon both mental and physical powers was relaxed for the present at least. An incident or rather a series of incidents, not uncommon in similar situations later in the war, but of which I believe this was among the first, marked our occupation of the Bowling Green road. It was apparent that the Confederates had established their outposts along the parallel ridge in front of us; and it soon became equally evident that the battle was not to be joined that day, and that our skirmish line was as far advanced as was practicable without precipitating an engagement. All remained quiet in our front; not a shot had been fired, and a mutual understanding not to begin hostilities appeared to have been established in some indefinable way between the two picket lines. Moreover, from time to time a Confederate would come out a few paces from the ridge and shout some good-natured badinage at us, to which we responded in a strain pitched to the same tune. A “Grayback” With a Handkerchief. At length a “grayback” was seen to advance, waving a handker-chief and offering to meet one of “you-uns” half way for a friendly confab. A ready response greeted the proposal, and one of the Thirteenth was soon sent forth with a well-filled haversack containing sugar, coffee, salt and hard tack, the joint contribution of his messmates.  The advance of

the friendly foes,

deliberately timed so that

they would

meet at a point equi-distant from either line, was eagerly and

excitedly watched by both sides. As the men neared each other

they were

seen to extend a welcoming hand, and then as the palms of “Johnnie”

and “Yank” met in a fraternal grasp an electric thrill went straight to

the heart of every beholder.

The advance of

the friendly foes,

deliberately timed so that

they would

meet at a point equi-distant from either line, was eagerly and

excitedly watched by both sides. As the men neared each other

they were

seen to extend a welcoming hand, and then as the palms of “Johnnie”

and “Yank” met in a fraternal grasp an electric thrill went straight to

the heart of every beholder.

Such a wild, prolonged and hearty cheer, such a friendly blending of Yankee shout and rebel yell as swelled up from the opposing lines surely was never before heard! The contents of the haversack were soon transferred to the adventurous reb, who in turn loaded our man down with native tobacco and bacon. As the afternoon wore on numerous similar affairs occurred, the utmost good fellowship being manifested. It was learned that our immediate opponents were the Nineteenth Georgia Regiment; they told us that they had tasted neither coffee, sugar nor salt for months. A Different Kind of a Meeting. We were fated to meet a large part of this regiment later on the next day, but as prisoners — and very cheerful ones, too — taken at the first charge of our line.1 They were as fine a set of fellows, for rebels, as we ever met during the war — intelligent, in short, excellent specimens of American manhood, among them being a graduate of Harvard College, whose name I have forgotten. All that night we remained on picket; no quieter night was ever passed in winter quarters. But at daylight the stir and bustle and hurried movements, the steady tramp of men, mingled with the vibrations of artillery wheels and rumbling of heavily loaded ammunition wagons, betokening an army on the march, were borne along on the morning breeze. Ready for Business. It was not far from 8 o'clock, I think, that the division of Pennsylvania Reserves came up, and immediately their pioneers attacked with axe, pick and shovel the road bank and soon a sufficient space was cut out for the passage of the troops and artillery. The impression will never leave me of the advance of the leading brigade as in close column it marched, gallantly out upon the open plain. The movement was evidently a blunder, for while they were still in motion General Meade, at that time commanding the division, attended by his staff, rode up to the gap, pausing there to survey the field. As I stood at my elevated post on the embankment I could have touched him by extending my arm. He sat his horse for a moment, and then excitedly raising both hands, cried: “Good God ! How came that brigade out there? No artillery — no supports! They will be cut to pieces!” And then he quickly dispatched an aide with some order to the imperiled troops, who were seen to hastily deploy, and another to hasten up a battery which soon came thundering through the gap and unlimbered just as a single shot came plunging along from the opposite woods followed by crash after crash from the rebel guns, and the air was filled with the shrieks of flying shells and solid shot! The battle on the left had begun.

Panoramic view of the Slaughter Pen Farm looking toward General Meade's position on the battlefield. General Meade's Division attacked toward the ridge in the background. Gibbon's Division. Our division — Gibbon's — was being formed to the right of Meade, and at this moment, and in the midst of this storm of shot and shell, we were hurried in that direction and thrown out to cover the former's position. Meanwhile the rebels had withdrawn down the slope and along the railroad track, and the ridge just relinquished was now occupied by our skirmishers. The “picnic” of the day before was evidently not to be repeated; a bloody struggle was before us. I remember how fair a morning it was, how balmy, even though in the midst of December, was the air, and how cheerful the sunshine as we moved out and took our station along the ridge, hearing at the same time the furious battle that was raging on the right, and eye-witnesses of the obstinate and bloody fight that Meade was making on our left. Drawn In. But now our own part of the field was to be involved. On a rising ground at our rear Hall's 2nd Maine battery had gone into position, and now his guns began to play over our heads into the woods that partially screened the Confederate works.

We were forced to lie down, for the Federal missiles came perilously low, Hall being compelled to depress his pieces in order to throw a plunging fire into the enemy's line. As an illustration of our danger from this source, following the discharge of one of the Maine guns, we heard a terrific screech down the skirmish line, and suddenly beheld a knapsack hurled into the air and one of our boys — of Company H, I think — was borne to the rear, dying, we were told on the way. A shell had torn through his side. [This is most probably George E. Bigelow, Company C. He died on the 19th of December. — B.F.] A Rebel Battery. A rebel battery posted in the edge of the woods was severely annoying our line of battle, which was lying down behind us waiting for the word to go into action, when Hall, suddenly concentrating the fire of all of his guns on that point, effectually silenced the rebel cannon. During the momentary lull that followed this achievement all eyes were at once directed toward the silenced battery by a terrific explosion, followed by the unique spectacle of an enormous and perfectly symmetrical ring of smoke rising slowly over the tops of the trees and sailing gracefully away until it became dissipated in the distance. A Rebel Caisson Exploded. Hall's last shot had exploded

a rebel caisson, killing and

wounding, as

was afterward learned, a large number of men. 2 But meanwhile we skirmishers were not idle. The rebel sharp-shooters had ensconced themselves among the limbs of the opposite trees, and were popping away at us and picking off the officers in the line of battle behind. Our own rifles were hot with constant firing, and every tree that sheltered a “Johnny” was made the billet for many a bullet. What execution our shooting did, as a whole, it was hard to tell. We now and then saw a rebel slide down from his cover and limp away; but it was at least equally effective, if not more so, than that of the enemy, for as we lay at the regulation distance of five paces apart the intervening ground was literally peppered with hostile lead, but up to a certain period not one of us had received a scratch. My Immediate Neighbor.

It happened, on this of all days, to be “Put's” turn to carry the mess wash-basin, a new and glittering affair recently bought of the sutler. We all had our knapsacks on, and as we lay on our bellies — firing in that position, turning sideways to load — it might have been thought that such an object, slung on the back of a knapsack, would afford a first-class mark for a Southern rifleman. We noticed, indeed, but without divining the cause, that the shots were coming a litlle thicker and faster about the particular spot where we lay, until a “Bucktail” — one of the famous Pennsylvania regiments, so named because they had adopted the device of wearing a buck's tail on their caps — who was next to me on the right, sang out: “Tell that cuss to take that d — tin pan off 'm his back !” A Bright and Shining Mark. I passed the warning to “Put” just at the moment when there came the sharp pish of a bullet, accompanied by a slight tintinnabulation — I am sure that must be the right word for it — and “Put” hastily tore off the basin. Such a comical look of stupefied consternation came over his face as he held up the bright object and exhibited a jagged hole completely through it, that we who beheld it fairly yelled with laughter. The next instant, with a frantic gesture, “Put” threw the thing from him, and it rolled with many a grotesque gyration down the slope almost to the rebel lines. That was close shooting, and we Northern veterans have good reason not to deny the abilities of “our friends the enemy” in that line. We all remember the characteristic story of the Northern traveler who witnessed the Kentucky lad sboot a squirrel dead with his pea-bore rifle and who began to blubber on examining his prize. “What's the matter, my boy? Why do you cry?” “Pap will give me a lickin' 'cause I didn't shoot the varmint through the head!” The Bugle — “Fall Back.” But now a sudden commotion in the rear, and the sound of our bugles to fall back, told that our long, harassing, and nerve-wearing duty was finished. Grandly came forward our line of battle, and the New York Ninth, whose front we had been covering — the noble, gallant, whole-souled boys of Brooklyn and New York city, with whom we had fraternized since the early days of '61 — opened its ranks to permit us to pass through, and then with a word of cheer that involuntarily partook, perhaps, of the nature of an adieu, we passed to the rear.4 Breathless We Waited! A minute, five minutes, perhaps more, perhaps less, for who can measure time at such a moment, and then a flame of fire and a cloud of smoke shrouded them from our view, as volley after volley of musketry, punctuated by the deep diapason of cannon and bursting shell, thundered and echoed over the plain. The advance and the retreat, the repeated charges and final bloody repulse, the brave stand-up fight our boys made, the useless, purposeless holocaust — all this is history, engraved forever on the hearts of the American people. And so, for us of the Thirteenth, ended the battle on the left. George E. Jepson. NOTES: 1. The 19th Georgia was

in Archer's

Brigade, which was overrun by the initial attack General Meade's

Division of Pennsylvania Reserves. About one-hundred of the

Georgians were taken prisoner when the Yanks surrounded their flank on

three sides. Reminiscence of David Sloss, Co. BWhen the above article appeared in the 13th Regiment Association Circulars, it prompted this response from the former color-bearer of the State Flag, David Sloss, which was printed in Circular # 20, Dec., 1907. Sloss settled in Chicago after the war, and was a policeman. His descendant shared the post war image with me. Chicago, Dec. 5, 1906. Dear Comrade Davis :

I received your circular to be with you the 13th, and as I will not be there, and as Jepson's article, on Fredericksburg interested me very much, I thought my experience there might interest you, as every one's story is different and we all like to tell what we have done in the past, and having time to burn and a constant physical reminder of those days; but my pen is not as skilled as you literary fellows. But you know the old adage, “Fools step in,” etc., and this is as cheap a way as I can do in return for all your kindness to one of the carriers of your old white flag. This is not taken from memory, as I have a diary and a letter of the 17th of December, 1862, so I will just copy them. The diary tells only cold facts, but the letter is more minute : “December 12, — Crossed the Rappahannock River about nine o'clock. Thrown out as skirmishers. Our line of advance carried me through the slave quarters. We were around what was called afterwards the 'Stone Hospital.' In one of the huts I found a large iron caldron which was full of boiled turnips. I fished in the pond and got a pig-skin about a yard long. I had no sooner held it up on my bayonet than it began to disappear, but I saved about a square foot of the turnips, which had coated it quite thick, and even now I smack my lips over the memory of that sweet taste that I got on that bright December morning so long ago. “We advanced over the Bowling Green road and halted where the incident of Blanchard (the old one) going out to meet the 19th Georgia man occurred. Also the Irishman's remark that the Georgians were there and they had their valises in the trees. “December 13. — Cold night. Called in to the regiment in the morning. Shelled pretty lively. Picked up a pocketbook with two hundred twenty-nine dollars, and fifty cents in stamps. This was in the Bowling Green road. A shell had killed some officer on horseback, and the pocketbook was lying in the road and half of the regiment had passed it by; as they were jerked away over the road they didn't see it. It was new, also the bills, and I carried it long after the war until it was worn out. The road was all in confusion. We went in again and skirmished for an hour, when we lost four killed and fifteen wounded, two in Company B. General Gibbon, our division commander, then advanced the 9th New York over us, and Johnnie Bell told George Hill to bid Davy 'good-by' for him. He was hit in the belly and died during the night.1 Johnnie Bell's father and mine were friends, and as I was told to look out for him when he came out to the 9th as a recruit after the Antietam fight when we were living off that corn field, on mush only. You can imagine he needed all my assistance, and our sutler's too, to keep him from that terrible disease, home-sickness, and the golden syrup at a dollar a can to help tide over that eventful two weeks until we got the regular supply. We then went down to the river to get ammunition, then went and supported Doubleday at an artillery duel. Two caissons blew up. “December 15. — The whole regiment on picket duty. In at 2 A.M. Found the army had re-crossed. We were in Taylor's brigade and he did nobly and also Gibbon, who was wounded in the wrist. Bayard was struck by a shell and died in front of the Stone Hospital. There was a crude map in the letter which I found in the pocketbook.” 2 Yours very

truly,

1.

The two Company B men wounded were, Privates James A. Young, and

William F. Blanchard. Sgt.

George Hill, Co. B (see his letter page 2) was a resident

of

Maine before and after the war. Mannsfield; The Bernard HouseThe Bernard Mansion was a prominent landmark on the battlefield were the 13th Mass. fought. It is mentioned in David Sloss's letter above as “the stone hospital.” The 13th Mass. regrouped here to replenish ammunition after their skirmish of two days. The following article about the Bernard House, or “Mannsfield” as it was known, is an excerpt of a post, “Digging Mannsfield,” dated December 3rd, 2010, on John Hennessy's [Fredericksburg National Battlefield] blog “Mysteries and Conundrums.” Please see the 'links' page of this site for more information. (I have omitted the 2nd part of the article about Park Service excavations.) Digging Mannsfield by John Hennessy (abridged) Spotsylvania has been particularly hard-hit by the loss of historic homes over the decades. In some areas, you can travel miles without coming upon an antebellum home — this on a landscape that was once liberally dotted with them. Some succumbed to war, more to neglect. And a few disappeared to the bulldozer's blade. Of all those that have vanished, none in its day shined more brightly than Mannsfield.

The remains of Mannsfield, probably in the 1870's. The ruins of the big house are at center; the north wing at left, and the south wing just on the right edge. These ruins stood until the 1920's. It stood about two miles south of downtown Fredericksburg, on the banks of the Rappahannock River. Mannsfield is today most famous as the site where Union general George Dashiel Bayard was killed at the battle of Fredericksburg —he was mortally wounded in the front yard and died just four days before what was to have been his wedding day. But, in fact, Mannsfield was probably the most impressive antebellum plantation in the Fredericksburg region, and one of the oldest, too. It was built in 1765-1766 for Mann Page III,* and it was close to being a literal copy of Richmond County’s Mount Airy, where Page’s mother grew up a Tayloe (the only major difference I can see is the design of the riverside entryway—otherwise the places seem to have been identical; Mount Airy still stands). Page was the Fredericksburg region’s first congressman, selected to the Continental Congress in 1777, at age 28. He died in 1803 and is buried in the nearby family cemetery—the only surviving feature of the Mannsfield complex.

Stuart Barnett's romantic vision of the west (front) facade of Mannsfield, showing the main house and wings. The house was anything but understated, built of sandstone blocks with two advanced, detached wings linked to the main house by a circular covered walkway. In the main house was nearly 7,000 square feet of living space, plus an elaborate basement. By the time of the Civil War (when Arthur Bernard owned it), thirty outbuildings sprawled across Mannsfield’s 1,800 acres (one of the biggest plantations around), including a stable, corn house, machine house, three barns, dairy, garden office, pump house, meat house, three poultry houses, ice house, a private owner’s stable, carriage house, overseer’s house, blacksmith shop, tobacco house, and six slave cabins (the site of some of these cabins, which in 1860 housed some of Bernard’s 77 slaves, is in the park off Lee Drive). Mannsfield’s prominence guaranteed it got attention in both peace and war. Washington reputedly visited here; so too did Union luminaries in 1862. For long stretches of 1862 and 1863, the house was in Confederate hands. Indeed, it was by the hands of Confederate pickets that the big house burned, accidentally, in early April 1863.

The standing ruins, looking at the west facade — looking southeast likely in the 1870's. The north wing is at left, the ruins of the big house faintly visible at center, and the remnants of the south wing at right. The ruins of the main house and the decaying remnants of the wings stood for six decades, until the early 1920s when artist Gari Melchers of Belmont acquired the accessible stone from the then landowner, R.A. James. According to local news reports, Melchers used stone from Mannsfield to build his new studio on the grounds of Belmont. *As with many Colonial gentrymen, confusion reigns when it comes to names and generations. There were in fact six Mann Pages. One — Mann Page’s younger half brother — died soon after birth. Most historians ignore his presence in the lineage and designate Mann Page (born 11749) of Mannsfield as Mann Page III, though in fact he was the fourth to bear that name. We can only be thankful Page wasn’t a Fitzhugh. There were TEN William Fitzhughs alive in the 18th century, scattered from Chatham to Annapolis. Austin Stearns MemoirsFrom "Three Years with Company K"; edited by Arthur Kent; Fairleigh Dickenson Press; 1976. (p. 144-148) Used with Permission. Just before the battle, Austin Stearns, now a

Corporal, was appointed

to the

Color-Guard. He

describes the event and the actions of the regiment on Dec.

12th & 13th. The sketch is his own. Note: Sgt.

Stearns confuses dates by 1 day. The army did march down to the

river on the 11th but they crossed the morning of Dec. 12th, and fought

Dec. 13th. On the morning of the 11th of Dec. 1862, in a thick fog, we marched down to the banks of the Rappahannock river about three miles below Fredericksburg; we were the left of the army. While halting a few moments waiting for the troops to cross on a pontoon bridge, Cap't Hovey ordered me to report to the color sergeant as a corporal on the color guard; the boys of K crowded around, some to shake hands, and all to say “Good by,” for they said “You are gone up now.” At Antietam, all the color guard but one was either killed or wounded, and judging from that, they thought my turn had come. The Color guard is composed of two Sergeants who carry the colors, one the National and the other the State, and eight corporals whose duty it is to guard the colors, and under no circumstances to allow the colors to be lost.

In a battle it is a great honor to take the colors of the enemy, and it is also a great dishonor to lose the colors, consequently the colors draws the hottest fire and some of the most desperate fighting takes place at the colors, and although at times it is a post of great danger, it is at all times a post of honor. We crossed the river, and fileing to the left marched down its banks. After passing a large stone house, the regiment, with the exception of the color company, deployed as skirmishers; the rebel skirmishers were in full view in the large open plain. The fog lifting at this time, and the sun coming out in all his glory, made a grand and beautiful sight; not a single gun was fired on either side, the rebels falling back in slow and even step as our own boys advanced. At the distance of a half mile from the river ran the Bowling Green Pike with a hedge on either side, and when we were ready to advance and occupy it, we thought they would dispute our possession, but no they quietly fell back to the field beyond. So passed the 11th. [12th — B.F.] Troops were getting into position all day long, and far up the river we could hear the great guns of both sides as they were maneuvering for position. We could see the signal flags of the enemy, and the guns on “Marye Heights.” Night settled down, our boys on the skirmish line held the pike, and we of the colors lay directly behind, while the line of battle lay in our rear. I went up to the right of the regiment during the night, drawn thither by a bright light caused by the burning of several hay stacks within the rebels lines. The night passed without any other alarm; to sleep was out of the question.

The 12th [13th — B.F.] dawned bright and clear; we were cooking our coffee early so as to be prepared for whatever might turn up. The skirmishers advanced beyond the pike, but no firing in our front. Private Blanchard of Co. B took his gun and, sticking it up in the ground by the bayonet, went boldly over to the rebel line to have a little chat with them, and trade some coffee for tobacco. Blanchard asked them “why they did not fire on our boys when we advanced”; they said “they did not like to be fired at any more than we did, and as we did not fire they had no occasion to.” He asked “when they would,” and they said “the next time you advance on us.” Blanchard went back to his place, and soon the order was given to “advance the skirmishers,” and the firing commenced. The rebels had now fallen back to the woods, and, lying behind the trees, had a better chance to pick us off who were in the open field without any shelter. They soon made it hot for us; some of the boys ran back a few steps to take advantage of the ground. Gen'l Taylor saw it and rode boldly up to the line and said “Boys why do you suffer those fellows to creep up on you in that way; your guns are as good as theirs; use them.” The bullets flew thickly around and we expected to see him fall, but he rode back unharmed. Although he sent his overcoat afterwards over to [Edward] Lee our tailor to be mended and there was six bullets holes in the cape. At last all the preparations were complete and the line of battle was ordered to advance, and the skirmishers were ordered to fall back after several hours of fighting. As we had used up about all our ammunition we were ordered to fall back to the big stone house and reform and refill our boxes. As we crossed the pike I saw Gen'l Bayard* sitting on his horse; a few moments later and he was instantly killed by a solid shot. While being served with ammunition I saw a fellow brought in on a stretcher who thought he was desperately wounded, one foot almost off he said; some of the boys examined him and could not find a scratch. A shell had come pretty close and frightened him; the stretcher bearers had found him lying on the field and thought him hit. After being supplied we again moved to the front, and while going we met a squad of reb prisoners coming to the rear. “What regiment,” some of the boys asked; they said “ — Georgia.” Warner of K asked them “What part of Georgia”; “Macon,” they answered. He lived in Macon before the war, but there were none that he knew. While we were talking the shells came over, striking the ground and throwing the dirt over us. One of the rebs, laughing, said “That is one of Stonewalls pills, and how do you like to take them.” “Oh, well enough,” we replied, “if they dont come any nearer than that.” Another one of our boys said “We're going to have Richmond now”; “Well,” said Johnie Reb, laughing heartly, “You'll find two Hills, a damned Longstreet, and a Stonewall before you get there.” All this happened in less time then it takes to write it.* When we got back to the pike, we found the brigade there, they having been driven back after some severe fighting. The fighting on the left was over for this day, and we held the same positon that we did in the morning, [with] nothing gained, but thousands killed or wounded. Night coming on, we lay in line of battle awaiting the morrow. *Generals Ambrose P. Hill and Daniel H. Hill, General James Longstreet, & General Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson. Next Page: Additional Stories Return to Top of Page | Continue Reading |

|

© Bradley M. Forbush, 2017 Page Updated September 13, 2018.  |

I shudder

to imagine

the fear and dread experienced

by the

Union soldiers who charged Marye's Heights during the Battle

of Fredericksburg.

At the base of the hill was a sunken road behind a stone

wall, where Confederate Infantry four rows deep fired repeated volleys

into any Federals that approached. Artillery from

the hill

above covered the field and bodies were literally blown to bits

during seven futile attacks against this impregnable

position. The

battle was a total disaster for the Army of the Potomac and its leader

General Ambrose E. Burnside.

I shudder

to imagine

the fear and dread experienced

by the

Union soldiers who charged Marye's Heights during the Battle

of Fredericksburg.

At the base of the hill was a sunken road behind a stone

wall, where Confederate Infantry four rows deep fired repeated volleys

into any Federals that approached. Artillery from

the hill

above covered the field and bodies were literally blown to bits

during seven futile attacks against this impregnable

position. The

battle was a total disaster for the Army of the Potomac and its leader

General Ambrose E. Burnside.

This was a

terrible

position to be in. An earnest protest was sent back

to

Captain

Hall, asking him to elevate his pieces, or every man of us would be

killed. Suddenly a shell or solid shot from this battery

struck

the cartridge-box of one of the boys while he laid on his stomach.

Some

of our number crawled out to where he lay and dragged him in.

He

lived about six days, having been injured in the hip. It was

bad

enough to be killed or wounded by the enemy, but to be killed by our

own guns excited a great deal of righteous indignation. [George

E. Bigelow, Company C is the

only man killed who died a few

days after the battle. You can read about him on the “Year's End,

1862,” page of this site].

This was a

terrible

position to be in. An earnest protest was sent back

to

Captain

Hall, asking him to elevate his pieces, or every man of us would be

killed. Suddenly a shell or solid shot from this battery

struck

the cartridge-box of one of the boys while he laid on his stomach.

Some

of our number crawled out to where he lay and dragged him in.

He

lived about six days, having been injured in the hip. It was

bad

enough to be killed or wounded by the enemy, but to be killed by our

own guns excited a great deal of righteous indignation. [George

E. Bigelow, Company C is the

only man killed who died a few

days after the battle. You can read about him on the “Year's End,

1862,” page of this site]. The sudden shock of hostile

forces unexpectedly meeting at the

intersection of lines of march, as at Gettysburg; the rapid overtaking

of the enemy, checking his advance and compelling him to turn at bay

like a cornered rat, as at Antietam; the halting of a flying

army in

full retreat, and the tremendous impact of advancing columns, as at

second Bull Run, each event bringing on the clash of arms with scarcely

an interval for thought — the serried ranks being precipitated upon

each other in the excitement and fervor of hot passion and under the

spur of suddenly aroused combativeness — a slap in the face as it were,

awaking ready resentment and quick reprisal — all this was vastly

different from lying for days, ingloriously inactive, awaiting the

means to cross a broad river, beyond whose watery barrier tantalizingly

stretched an unobstructed path to the goal that had so often and so

mockingly eluded, so to speak, our persistent and bloody endeavors to

attain it; beholding a position of incalculable importance

inviting

peaceful occupancy, gradually being covered by a hostile army, while

we, in enforced idleness, witnessed

day by day the augmentation of the enemy's forces and noted his busy

toil and strenuous preparations to strengthen and render

impregnable a vantage ground formidable enough in its natural naked

ruggedness.

The sudden shock of hostile

forces unexpectedly meeting at the

intersection of lines of march, as at Gettysburg; the rapid overtaking

of the enemy, checking his advance and compelling him to turn at bay

like a cornered rat, as at Antietam; the halting of a flying

army in

full retreat, and the tremendous impact of advancing columns, as at

second Bull Run, each event bringing on the clash of arms with scarcely

an interval for thought — the serried ranks being precipitated upon

each other in the excitement and fervor of hot passion and under the

spur of suddenly aroused combativeness — a slap in the face as it were,

awaking ready resentment and quick reprisal — all this was vastly

different from lying for days, ingloriously inactive, awaiting the

means to cross a broad river, beyond whose watery barrier tantalizingly

stretched an unobstructed path to the goal that had so often and so

mockingly eluded, so to speak, our persistent and bloody endeavors to

attain it; beholding a position of incalculable importance

inviting

peaceful occupancy, gradually being covered by a hostile army, while

we, in enforced idleness, witnessed

day by day the augmentation of the enemy's forces and noted his busy

toil and strenuous preparations to strengthen and render

impregnable a vantage ground formidable enough in its natural naked

ruggedness.

My immediate neighbor on the

left was N. M. Putnam.3 “Put,” as

he was

familiarly called, was the model of a soldier; one of those men

of

sturdy New England build, morally and physically, always ready for any

duty, and who could never acquire, apparently, the first principles of

the art of shirking, whether it was that of the most disagreeable

police duty or the more dangerous one of keeping his file in the face

of bursting shell and a storm of leaden hail, presenting, moreover, the

rare example of an old soldier who never drank a drop of intoxicating

liquor, never smoked or chewed tobacco, was absolutely insensible to

the fascinations of poker, loo or seven-up, and was never known to

indulge in even the mildest and most innocuous cuss word.

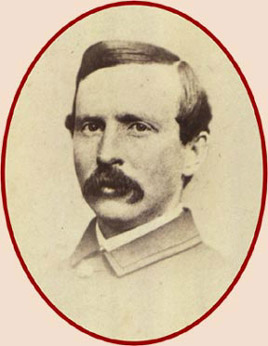

[Nathaniel M. Putnam,

pictured.]

My immediate neighbor on the

left was N. M. Putnam.3 “Put,” as

he was

familiarly called, was the model of a soldier; one of those men

of

sturdy New England build, morally and physically, always ready for any

duty, and who could never acquire, apparently, the first principles of

the art of shirking, whether it was that of the most disagreeable

police duty or the more dangerous one of keeping his file in the face

of bursting shell and a storm of leaden hail, presenting, moreover, the

rare example of an old soldier who never drank a drop of intoxicating

liquor, never smoked or chewed tobacco, was absolutely insensible to

the fascinations of poker, loo or seven-up, and was never known to

indulge in even the mildest and most innocuous cuss word.

[Nathaniel M. Putnam,

pictured.]