The Maryland Campaign

September 10th - 17th 1862

"We were back in Maryland, which we left six months before. While the progress we had made toward crushing the rebellion was not very flattering, it afforded us pleasure to be again marching among loyal people who had an interest in our welfare.

We were now about half-way between Washington and Darnestown, the place where we were encamped a year ago. Then we were a thousand strong; but now we had dwindled to half that number. Some were killed, and a good many in hospitals, wounded or sick, never to return."

Walton

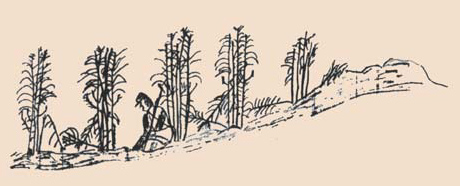

Tabor's

illustration depicts the Union charge through Miller's

Cornfield;

men from Duryea's Brigade in the early morning attack about 6 A.M.

The boys of the '13th Mass.' followed them up about

6:30 A.M.

"We are three miles from Sharpsburgh. The army is in high glee. McClellan, the little man of destiny, bronzed face, passed us yesterday, and the day before, cheered every step of the way. Our regiment is not a cheering regiment, but at the coming of McClellan every man was on his feet hat in hand. What a look he gave at our tattered colors, as he passed in amid redoubled cheers." - private John B. Noyes, letter to his father, Sept. 16, 1862.

- Introduction

- Campaign Narrative: New Recruits; Sept. 10, 1862

- Pursuit of Lee's Army: Battle at South Mountain; Sept. 14 - 15, 1862

- Short Summary of the Battle of Antietam

- George W. Smalley's Report of the Battle

- The Memoirs of John Sawyer Fay

- Colonel Coulter's Battle Report (Hartsuff's Brigade)

- Sergeant Austin Stearns Memoirs, Company K

- Letter of Major Gould to Colonel Leonard

- Diary of Samuel Derrick Webster, Company D

- Letter of John B. Noyes, Company B

- Levi L. Dorr Reminiscences, Company B

- Letter of Warren H. Freeman, Company A

- Letter of Prince Dunton, Company H

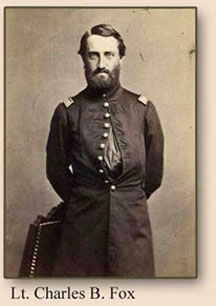

- Letter of Charles B. Fox; Tending to the Wounded

- Westborough Transcript; Casualty List for Co.'s F, I, & K

- Letter of James Lowell, Co. A; (battlefield experiences)

- Letter of John B. Noyes, Co. B; (summary of the campaign)

- Letter of Warren H. Freeman, Co. A; (battlefield experiences)

- Lt. Charles B. Fox's Casualty List

- Adna P. Hall, Company H

- Short Service

Introduction

Political Implications of the Campaign

General Robert E. Lee's exhausted, but re-enforced Confederate Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland directly after defeating Major-General John Pope's army at the battle of 2nd Bull Run. The Army Lee's objective was to carry the fight north of the Potomac, out of Virginia, and if feasible enter Pennsylvania. If successful the Confederate government could propose a cessation of hostilities in exchange for Southern Independence. If the proposal for peace were rejected by Lincoln's government it could still impact northern voters in the fast approaching elections. Voters could choose between those who wish to prolong the war or those who wish to pursue peace. In any case, Lee was in Maryland to inflict injury on "our adversaries" and to "annoy and harass the enemy." He planned to attack the Union Army, thinking it was too demoralized to win a fight. The plan was audacious, but so was General Lee While he depended upon his army alone for victory, the Confederate government was hoping to gain recognition from Europe.

The Union Naval blockade kept southern cotton from textile mills in England and France where it was desperately needed. Their mill workers were put out. Those two countries were leaning toward Confederate recognition, but prudent England decided to take a wait and see attitude. President Lincoln's Secretary of State, William H. Seward proclaimed European attempts at mediation in the Civil War would be an act of war. When news of the Union defeat at 2nd Bull Run reached London, 2 weeks after the battle, the British government thought it was finally time to consider intervention on behalf of The South. Meanwhile, President Lincoln waited uneasily for a northern army victory so he could announce his "Emancipation Proclamation," which freed the slaves in openly rebellious states. He knew England could not morally support a nation that condoned slavery, at war with another which did not.

Troop Movements

After a few days rest at

Frederick, MD, General Lee made some

plans. The intended supply route for his

Northern invasion was the Shenandoah Valley, and he needed to clear out

the Federal garrisons there at Martinsburg and Harper's

Ferry. General McClellan wanted these outflanked posts

evacuated, but Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck insisted they be

defended. To capture these forces, General Lee divided his

army in half. General Stonewall Jackson's wing would divide

into 3 sections and attack Harper's Ferry on September 12th, from the

North, East and West. The Union troops at Martinsburg were

expected to retreat to the larger garrison at Harper's Ferry.

Lee's supply train and the rest of his army would wait in Boonsboro,

across South Mountain, shielded from Federal view. The army

moved out September 10th.

General McClellan had the love and confidence of his army but not of the administration. His presence as commander tremendously boosted morale. He followed Lee into Maryland, seeking information on the motives and size of the Confederate Army. McClellan’s force cautiously spread out over 25 miles, to be ready to cover Baltimore or Washington1 or enter Penn. depending on the motives of the enemy. Faulty reconnaissance by his own men, suggested his army was greatly outnumbered by the rebels; a chronic complaint of 'The Young Napoleon.' By chance, on the morning of September 13th, when going into camp at Frederick, MD, Corporal Barton Mitchell of the 27th Indiana discovered a map of Lee's plans wrapped in a package of 3 cigars. They were quickly brought to Gen. McClellan's headquarters and authenticated. Crucial was the discovery that Lee had divided his force. McClellan knew he had the means to destroy Lee's army and telegraphed the President as much.

On September 13th, the Union Army moved west through the town of Frederick toward the South Mountain passes.2 The morning of September 14th General Franklin's corps advanced to Crampton's Gap, his objective the relief of Harper's Ferry. McClellan approached Turner's Gap 7 miles north of Crampton's Gap. The Union advance surprised General Lee, who had divided his wing of the army further still, and he had to scramble to get troops from far away Hagerstown up to Turner’s Gap on South Mountain to head the Yankees off at the pass. The Confederates were slow in coming, but the Yankees were even slower. Confederate General D.H. Hill was lucky and successful in giving the Federals a good fight for control of the mountain passes and he managed to slow the Union advance with an all day fight that lasted until dark. (General James Longstreet’s troops arrived in time to give support.) At night Lee and his subordinates, Generals Longstreet and D.H. Hill,decided to retreat from the mountain before dawn. The Union victory gave McClellan's long suffering troops something to celebrate.

Seven miles south at Crampton's Gap,

General

Franklin’s aggressive Division Commander Major-General Henry

Slocum charged the hill in the afternoon and took the mountain pass

from the Confederate defenders. But Franklin’s glacial pace

was no help to the Federals trapped at Harper's Ferry.

Jackson's 3 pronged attack forced the surrender of the Garrison the

morning of September 15th.

Seven miles south at Crampton's Gap,

General

Franklin’s aggressive Division Commander Major-General Henry

Slocum charged the hill in the afternoon and took the mountain pass

from the Confederate defenders. But Franklin’s glacial pace

was no help to the Federals trapped at Harper's Ferry.

Jackson's 3 pronged attack forced the surrender of the Garrison the

morning of September 15th.

With the Yankees on his tail, Lee's spread out army was in peril. He sent orders to Jackson at Harper's Ferry to make haste and re-unite the army at Sharpsburg. Lee then formed his half of the Army of Northern Virginia into a line of battle on the high ground near the town, facing the Federals across Antietam Creek. Lee's show of defiance led the super cautious McClellan to pause and ponder what to do next as his army marched down the mountain, through Boonsboro to Keedysville. The Army of the Potomac bivouacked on the roads around the village, just east of Antietam Creek. Bad intelligence still led McClellan to believe the Confederates greatly outnumbered his own troops. The opposite was true. On September 15th and 16th McClellan outnumbered Lee's available force by 4 to 1. McClellan's fighting strength was about 71,500 troops. About 18,000 were fresh troops, totally green without any training.3 Lee at this moment had about 26,500 men at hand, yet the Union high command estimated Rebel strength to be between 100,000 and 135,000 men.

The two day pause of the Union Army bought desperately needed time for the Rebel army to concentrate.

General McClellan’s battle strategy was sound. He attacked Lee’s line on both flanks, forcing the Confederates to use up their reserve troops. The final strike was to be a decisive knock-out blow delivered by a huge attack force massed in the center of the Union line. It was to strike in either direction at an opportune moment during the battle. One flaw however, was that the entire Union Cavalry was part of this force, which prevented the Union command from gaining any intelligence about enemy movements on the flanks, especially in the direction of the river crossings towards Harper’s Ferry and Shepherdstown.

Major-General Joseph Hooker's First Corps opened the battle on the Confederate left flank, assisted by the 2nd Corps, Major-General Edwin V. Sumner and the 12th Corps, (formerly Major-General N.P. Banks Corps) now commanded by Major-General Joseph K. Mansfield. Major-General Ambrose E. Burnside's 9th Corps delivered the 2nd attack on Lee's right flank, across the Rhorsback bridge.

On September 16th around 4 p.m., Hooker’s First Corps began crossing Antietam Creek to get into battle positions. The Confederate line shifted to meet the to meet the forthcoming attack.

NOTES: 1. Editor Tom Clemens cites an communication from General Halleck reprimanding McClellan for moving too quickly and leaving Washington uncovered during the advance; to be found in the Official Records 19 pt 2, pp 211, 216; ibid, pt 1, pp 25-7, 39-41; from “The Maryland Campaign” Vol. I, Ezra A. Carman, edited and annotated by Thomas G. Clemens, pp 172 -3, note 24.

2. McClellan is criticized by historians for not advancing further toward South Mountain on the night of Sept.13th after Special Order 191 was discovered. Thos Clemens makes a good point in Vol. I of “The Maryland Campaign” (Ezra A. Carman) Most of the army was already in motion that day when Special Order 191 was found. The second and ninth corps caused a traffic jam as they moved through the town of Frederick forcing the 12th Corps to halt east of town. And Confederate rear guard forces were a problem until early afternoon. Two divisions of the 9th corps did move into the Middleton Valley the night of the 13th. “It is also worth noting that on Sept 14, Halleck was still notifying McClellan about large numbers of troops in Virginia, and warning him about exposing his flank and rear” [p. 290; note 17.]

3. Thomas Clemens’s wrote, “This editor’s research arrives at a figure close to 18,000.” From The Maryland Campaign, vol. I, Ezra A. Carman, edited and annotated by Thomas G. Clemens [p.149, note 68].

The Battle; September 17, 1862.

The following is lifted directly from the Antietam National Battlefield Park description of the fight.

"The twelve hour battle began at dawn on the 17th. For the next seven hours there were three major Union attacks on the Confederate left, moving from north to south. Gen. Joseph Hooker's command led the first Union assault. Then Gen. Joseph Mansfield's soldiers attacked, followed by Gen. Edwin Sumner's men as McClellan's plan broke down into a series of uncoordinated Union advances. Savage, incomparable combat raged across the Cornfield, East Woods, West Woods and the Sunken Road as Lee shifted his men to withstand each of the Union thrusts. After clashing for over eight hours, the Confederates were pushed back but not broken, however over 15,000 soldiers were killed or wounded.While the Union assaults were being made on the Sunken Road, a mile-and-a-half farther south, Union Gen. Ambrose Burnside opened the attack on the Confederate right. His first task would be to capture the bridge that would later bear his name. A small Confederate force, positioned on higher ground, was able to delay Burnside for three hours. After taking the bridge at about 1:00 p.m., Burnside reorganized for two hours before moving forward across the arduous terrain - a critical delay. Finally the advance started only to be turned back by Confederate General A.P. Hill's reinforcements that arrived in the late afternoon from Harper's Ferry.

Neither flank of the Confederate army collapsed far enough for McClellan to advance his center attack, leaving a sizable Union force that never entered the battle. Despite over 23,000 casualties of the nearly 100,000 engaged, both armies stubbornly held their ground as the sun set on the devastated landscape."

The '13th Mass.' at the Battle (Ricketts Division, Hartsuff's Brigade)

The following borrows heavily from the book, “Landscape Turned Red” by Stephen W. Sears; Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983.

General Hooker's attack goal was a "raised open plateau just to the east of the Hagerstown Turnpike in front of the Dunker Church." He planned to attack "due south toward the Dunker Church along the axis of the Hagerstown turnpike." Brigadier-General Abner Doubleday's Division, "would advance on the right, along the pike and through the Miller farm toward the West Woods, with James Ricketts' Division on the left, through the Cornfield and the East Woods. George Meade's Division would back them up in the center."

No provision was made for a joint attack with Mansfield's Twelfth Corp. Hooker's First Corps strength was about 8,600 men. His opponent, Stonewall Jackson had about 7,700 men to meet the attack.

Very early in the morning, Brigadier-General Truman Seymour's Pennsylvania Buck-tails skirmished in the East Woods while General Hooker got his attack force ready. When General James Ricketts moved the 3 Brigades of his Division out of the North Woods on Joseph Poffenberger's Farm, enemy artillery spotted them and opened fire. "Scores were knocked out of the ranks before they were on the field 5 minutes." Brigadier-General Abram Duryea's Brigade led the advance to the Cornfield with two artillery batteries in support. The guns of Captain Ezra Matthews, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery F, and Captain James Thompson's Pennsylvania Light Battery C, advanced with Duryea to the cornfield and dueled with the Confederate Artillery posted near the Dunker Church. At 6 A.M. Duryea's 1,100 men from New York & Pennsylvania entered Miller's Cornfield. Duryea's Brigade fought alone for about 30 minutes without support.

This map shows the portion of the field where the 13th Mass fought. Map boundaries extend from Dunker Church at the intersection of Smoketown Road and Hagerstown Pike, (bottom center) north to the farm of Joseph Poffenberger where the 1st Corps formed battle lines. Gen. Hooker's objective was the plateau where Col. Stephen D. Lee's Confederate artillery was posted. The map shows Duryea's attack; 6:00 to 6:20 a.m.

General Ricketts other two brigades ( Brigadier-General George Lucas Hartsuff and Colonel William A. Christian) suffered a break-down in command which delayed the advance. Hartsuff was supposed to lead the attack with Duryea and Christian in close support. The first delay happened when General Hartsuff went forward to reconnoiter and was badly wounded by a shell fragment from enemy artillery. Between the confusion of the command change and a mix-up of orders, his entire brigade remained standing under arms back in Poffenberger's meadow while Duryea's lines were broken and driven back in the cornfield. Finally everything was straightened out. Colonel Richard Coulter assumed command and hurried the brigade forward.

As the columns of Christian's Brigade approached the East Woods they came under a deadly cross fire of Rebel artillery. Col. Christian had a sudden break-down, dismounted and ran to the rear. "While Christian's Brigade was trying to sort itself out, Hartsuff's troops under Colonel Coulter emerged from the Cornfield and the East Woods to meet a blizzard of fire." The Confederate artillery had their exact range.

Confederate General Lawton was facing the Yankees on this part of the line and his thinning force began to waiver. He called for reinforcements and up charged the infamous Louisiana Tigers, who with some of Lawton's Georgians, came head on at Col. Coulter. A Southern war correspondent for the Charleston Daily Courier, described the scene this way, "The fire now became fearful and incessant,…merged into a tumultuous chorus that made the earth tremble. The discharge of musketry sounded upon the ear like the rolling of a thousand distant drums…" Thompson's Battery moved into the cornfield to support the Union line and blasted the Tigers and the Georgians until they fell back. The fight in the cornfield was about an hour old at 7 A.M. when Christian's Brigade led by Colonel Peter Lyle of the 90th PA finally advanced through the East Woods. "Col. Coulter hurried back from the front line, found Lyle and called out, "For God's sake, come help us out!" Coulter's wrecked formations were pulled back and Lyle's men took their places." In his report of the battle Colonel Coulter wrote, "The Thirteenth Massachusetts had disabled three officers out of twelve taken into action. I would here make especial mention of Major Gould, commanding this regiment. He brought his men well into action, by his gallantry maintained and encouraged them while there, and was among the last to leave the field."

Battle Map No. 2 shows the attack of Hartsuff's Brigade, commanded by Col. Richard Coulter.

The battle-line of the Thirteenth Massachusetts extended partially into the East Woods, which provided some shelter from enemy fire for those men. The accounts of the soldiers suggest some of them fought longer than the rest of the brigade, due to this protection. Their sister regiment, the Twelfth Massachusetts, was totally exposed on high open ground. This organization suffered the highest casualty rate of any regiment in the fight this day. The usual statistic given states the '12th Mass.' lost 224 men out of 334 taken into battle, (67 % loss). But like the '13th Mass.,' the 12th had a post-war Regiment Association, and in the annual circular of 1897, historian George Kimball states that only nine of the 12th Regiment's ten companies were in the action, and that losses were 222 of 262, or 85%. Lieutenant Charles B. Fox compiled a careful list of the 13th Regiment's losses. A transcription of the list is included on this page. Charles E. Davis, Jr. stated in the Thirteenth Massachusetts regimental history, "We took into this fight three hundred and one men, and brought out one hundred and sixty-five, a loss of forty-five percent."

Picture Credits: All pictures & maps come from the Library of Congress digital collections except where indicated. The graphic "Into the Cornfield" by artist Walton Tabor is from Century's publication, "Battles & Leaders of the Civil War." South Mountain Inn images come from the Maryland Historical Register; and images of Boonsboro, from the Western Maryland Room of the Hagerstown Library. Soldiers of Co. B (Worcester, Dorr, Richards, Armstrong, Whidden, Samuel S. Gould, & Adna Hall's breastplate) were shared with me by private collector Scott Hann. Captain Eben Fiske, John B. Noyes from Massachusetts Historical Society; John S. Fay, Charles N. Richards, James Lascelle Forbes, Adna P. Hall from descendants of these men, Gen. Hartsuff from Robert Moore's blog,; Confederates marching through Frederick from Harry Smeltzer's blog; Col. D. H. Strother, Captain Charles Hovey, Lt. Charles B. Fox, J.H. Cutting, from Mass. MOLLUS Collection, Carlisle, Army Heritage Education Center; battlefield snapshots by webmaster Brad Forbush, taken March, 2005; Abel H. Pope from Hudson, Mass. Historical Society; Dead at Antietam from, "Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes", Francis Trevelian Miller, 1911; Austin Stearns' sketch of the cornfield from "Three Years with Company K" ed. by Arthur Kent, 1975.; Enoch C. Pierce, Maj. J.P.Gould, Alfred W. Brigham, Eugene Allen Fiske, Will Soule, Walter Pollard, J. P. Shelton, Edward Archibald, from various online auction houses. Charles R. Dale shared with me by Steve Heintzleman of Stoneham, Mass. ALL PHOTOS HAVE BEEN CROPPED AND RETOUCHED IN PHOTOSHOP.

Campaign Narrative: New Recruits; Sept. 10, 1862

From "Three Years in the Army" by Charles E. Davis, jr. Estes & Lauriat, Boston, 1894.

Wednesday, September 10.

Yesterday at 4:15 P.M. we marched to

Mechanicsville, about eight miles, where we now were.

We received another lot of recruits to-day, and a fine looking set of men they were. It is a notable fact that this batch of recruits was the last in which we had any feeling of pride. Up to and including this time we had been fortunate in our recruits. They were a credit to the State and reflected honor upon the regiment; they were in such marked contrast to those who followed that the fact is worth mentioning.

Disappointment and

mortification was the lot of one of this

number, who came to us full of confidence and hope. Having

completed his school education he was seized with the patriotic desire

to enlist, and leaving the tender care of mother and father he joined

the Thirteenth. His first shock was at our appearance.

Instead of bright uniforms, with gilt buttons and shoulder

knots, he found us with ragged trousers, ill-fitting blouses, and torn

and faded caps - the result of long marches over dusty roads and

bivouacking in ploughed fields, that made us look more like

a regiment of tramps than soldiers.

On the morning following his arrival, our new recruit made inquiry of his comrades as to where he was to get milk for his coffee, and was told that the captain kept the milk in his tent. Having perfect confidence in his comrades, he made application at once. The captain was surprised at the request, and explained to him that milk was not in the list of articles of diet provided by the Government. Of course the recruit felt mortified at his mistake, but made the best of it, though it destroyed his confidence for a while in his associates' statements. He learned that "Ask and ye shall receive" had no coinage in the army. Notwithstanding his verdancy he became an excellent soldier.

Most of us cared little about the deprivation of milk, though the temptation was strong among some of the boys, when sighting a cow, to ascertain if they had lost the trick of milking. Although a cow, under ordinary circumstances, is a peaceable animal, she draws the line when her lactar reservoir is being too energetically pumped. To hold a dipper with one hand and milk with the other, particularly when three other hands were endeavoring to do the same thing on the same cow, and she unwilling to stand still, required a degree of skill that few of us possessed. In spite of being well-aimed, the stream of milk would generally go in any direction but that of the dipper; hence the necessity of struggling with this problem when no other soldiers were about, unless you were fond of unrewarded labor. Therefore most of us preferred buying it at farm-houses, though the demand was so much greater than the supply, we were often disappointed in our efforts to obtain it. When the sutler was with us we could buy "condensed milk," which we found an excellent substitute.

Thursday, Sept. 11.

At 9 A.M. we started on the march and

kept it up all day, in a

slow, tedious manner, until we paced off twelve miles on the road to

Frederick.

Friday, Sept. 12.

After inspection in the morning we

marched to Ridgeville, seven

miles, and camped.

Saturday, Sept. 13.

We started at 1 P.M. and marched twelve

more miles toward

Frederick.

Pursuit of Lee's Army: Battle at South Mountain; Sept. 14 - 15, 1862

An Astonshing Discovery (From "Three Years in the Army," by Charles E. Davis, Jr.)

Sunday, September 14.

At 5 A.M. we broke camp and marched all

day with frequent and

uncertain halts, passing through Frederick and Middletown, untl about

six o'clock, when our division (Hooker's) was placed in second line of

battle on South Mountain. As we climbed up the steep sides of

the mountain we were fired at by the enemy, who made the very common

mistake of soldiers when firing from an elevated position, - that of

firing too high, - by which means we escaped any casualties.

We laid on our arms until morning.

The unexpected often happens in the army. When we retreated from Manassas, the afternoon of August 30, we gave up all hope of seeing our knapsacks again, as the grove where they were deposited had been taken possession of by the enemy. During our advance up the mountain to-day, the dead body of a rebel belonging to a Georgia regiment was seen lying on the ground near the road, where he was killed. One of our boys, regretting the loss of his knapsack, and noticing the Reb had one, concluded to make good his loss by transferring it to his own back. Now the most astonishing thing about this was the discovery, upon removing the knapsack, that it was his own property, which had been toted from Manassas to South Mountain by a rebel soldier. He was still more amazed on opening it to find the contents had been undisturbed.

Austin Stearns Describes the advance from Frederick (From "Three Years With Company K" by Sergeant Austin C. Stearns, (deceased) Edited by Arthur Kent, Associated University Presses, Cranbury, NJ, 1976; (p.119-123) Used with permission.

How beautiful it looked on this pleasant sabbath morning, the 14th day of September 1862, to see the army winding up on the ridge, the Sun shining brightly, flags waving, and bayonets glistning. If that was a glorious sight, how much more so was the sight when we had reached the summit of the ridge and could look down and across the valley, to see the fields and farm-houses in all their quiet stillness extending up and down in this "garden of Maryland." Looking straight across the troops could be seen, winding their slow length along, the advance of the union army contending with the rear of the rebels, the rugged slopes of South Mountain in the not very far distance.

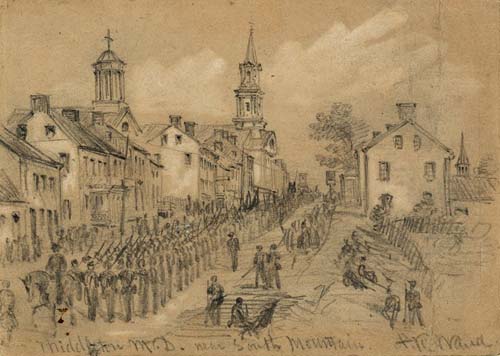

Down the west side of the ridge and across the valley we pushed. All thoughts of our recent defeats was for the moment forgotten, for in our front were the enemies of our country, and the old thoughts and feelings, and love of country, flag, and home came back, and how eager we all were to again measure our strength with the enemy, and wipe the stain of defeat away. Most of us privates knew that if there was concert of action amongst the leaders, that we could whip the enemy upon any field. So we marched on down the ridge, across the valley and through the village of Middleton on that sabbath day.

We were halted by the side of the road with our guns stacked, waiting for the division of Gen'l Reno to pass, when an officer approached surrounded by a brilliant staff. The Col. ordered us to fall in and "give three cheers for George B. McClellan, Commander in Chief of the Potomac Army." Of course we cheered, for a good soldier always obeys.

McClellan in acknowledgement of the compliment raised his cap and rode on. Soon we followed, and on coming to the foot of the moutain we turned to the right and went a half mile or so, when we halted and orders were given to "pile knapsacks," and leaving them under a guard we formed a line of battle and commenced the ascent. The battle in the meantime was going on, Cox's divison being engaged at the pike road and at the left of it, while Reno's division was engaged at the right of Cox's. We formed on the right of Reno's, when about two thirds of the way up the left of our brigade became engaged; we being on the extreme right were not actively engaged, although the left of the reg't was where there was some firing and the bullets sang merrily over our heads. Darkness coming on, the troops halted then and there with orders to sleep on our arms, without any blankets, and not allowed a fire, not even to strike a match to light a pipe. We shivered through the night.

How my teeth chattered with the cold. We huddled together and tried to keep warm. The officers were as cold as we were; a group of them was standing but a few feet from where we lay when a stragler coming up in the dark addressed them:

"Can you tell me where the 11th P.V.'s are?"

"Do you belong to that regiment?" said Col Coulter.

"Yes sir," meekly replied the soldier, and recognizing his Col. and not daring to say anything but the truth.

"How did you lose your regiment then?" said the Col.

"I fell out," he replied.

"Well, do you see that black line," said the Col., pointing towards a black line that could be seen through the darkness. "Well, that is the 11th P.V.'s and do you double quick to it in no time, or I'll put you in a place where you can't stragle."

The soldier, knowing the metal of his commander, left his presence in quick time for his regiment, well satisfied to escape so easy.

Morning at length dawned and our lines were reformed and preperations were made for an advance. Hooker was there directing the movements. Gen'l Meagher, of Richardson divison, with his brigade was forming on the right of us, and not taking room enough overlapped almost our entire regiment.

"Move those troops farther to the right," said Hooker.

"By whose orders?" said Meagher, turning towards him.

"Major Gen'l Hookers, sir"; no more was said, Meagher moving the troops. Companies D. and K. were deployed as skirmishers and sent forward into the woods, taking our places on the line of skirmishers; the order "forward" was givein and we advanced to find no enemy in our front, for they were discovered to be in full retreat. Immediately we were filed off to the left through the woods, and coming out on the west side of the ridge near the "Mountain House," we halted for breakfast. Our rations were runing low, for we had marched so fast that the commssary had not been able to keep up; two hard bread to a man was issued, a scant meal to march and fight on.

Dan Warren, in looking over the premises, found two eggs and a half dozen potatoes, I found a few onions, and we put them together and had quite a meal out of the whole. After halting a few hours we descenced the ridge, pushing on after the retreating rebs, their rear and our advance fighting all the way. We went down through Boonsboro, a place we had visited in our earlier life as a soldier, and on towards Sharpsburg.

Pictured is the Commercial Hotel, Boonsboro, 1887. The hotel has a long history; probably built in the 1790's. At the time of the Civil War it may have been called the Eagle Hotel, but it has had several different names through the centuries. One can picture the soldiers marching down this street with colors flying, the buildings decorated with bunting and flags. Doug Bast allowed the Hagerstown Library to post this image.

Division Commander, General James B. Ricketts' Report:

On the morning of the 14th instant the division was under arms to march at daylight from its encampment near the Monocacy, and arrived at the east side of South Mountain, about a mile north of the turnpike, at 5 P.M., forming line of battle, First Brigade, Brigadier-General Duryea, on the extreme right; Third Bridgade, Brigadier-General Hartsuff, in the centre, and Second Brigade, Colonel Christian, on the left. The route of the First and Third Brigades extended over a very rough ground to the crest of the mountain, which was gallantly won. On the left the Second Brigade was sent to the relief of General Doubleday's, which was hard pressed and nearly out of ammunition. It engaged the enemy with terrible effect, and drove him down the west side of the mountain.

It being now too dark to advance, and the men much exhausted, operations ceased for the night. The next morning, the enemy having fled during the night, the division moved forward and encamped near Keedysville. The artillery was not engaged.

In his report on the battle of South Mountain, General Hooker makes the following statement:

It being very dark, our troops were directed to remain in position, and Hartsuff's brigade was brought up and formed a line across the valley, connecting with Meade's left and Hatch's right, and all were directed to sleep on their arms.

At dawn, Hartsuff's skirmishers were thrown forward, supported by his brigade, to the Mountain House, a mounted picket of the enemy retreating as they advanced. The enemy had been re-enforced by twenty regiments of Longstreet's corps during the early part of the night, but between 12 and 1 o'clock commenced a hurried and confused retreat, leaving his dead on our hands and his wounded uncared for.

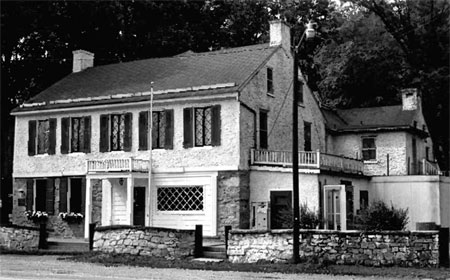

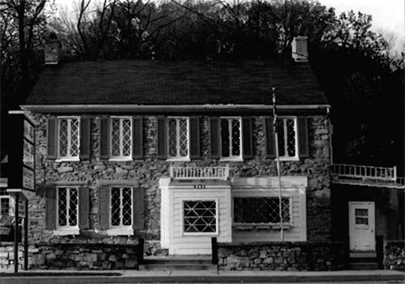

The Old Summit House

The Mountain Tavern, as Sam Webster called it, or the Summit House, as John S. Fay calls it, still exists. The structure was built in the 1700's. Today, it's a restaurant called the Old South Mountain Inn. Webster and Fay wrote that the regiment halted for breakfast here, in front of the old tavern. At the door of the tavern General Hooker received the party of rebels under a flag of truce, who came to retrieve the body of Brigadier-General Samuel Garland, a promising young general killed at Fox's Gap the moring of September 14th. Garland was at the front with his North Carolina brigade fighting back the advance of two Ohio Brigades of the 9th Corps, lead by Colonel Eliakim Scammon and Colonel George Crook.

From the

Diary

of Samuel Derrick Webster, Company D

Excerpts

of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission

from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

Thursday September 11th,

1862

Were to move yesterday but

re-encamped. Rained. Marched to Cooksville today,

and to a short distance west

on the

pike. Took

possession of a hatchet found

sticking in a post. Rain

again

today. 16th Maine

furnish several pieces of music from

their large drum corps.

Friday, September 12th.

Marched to Ridgeville. 68

rebel

cavalry were here yesterday. Got bread from one of cousin

Emma Webster’s

acquaintances

– says she

knows me – maybe she does. Only

about 20

miles from Westminster.

Saturday, September 13th.

Moved up near Frederick,

crossed the Monocacy at dark. Water

scarce and I feeling very feverish. Many

stragglers. Rebels

were driven from here

today by our advance.

Sunday, September 14th,

1862

Advance to Mountain beyond Middletown.

At foot of Mountain turned to the right, and along the

stream until we

came to a little

brick church. Turned

up the mountain. Left

knapsacks at a brick farm house. Johnny

Towne too sick to go further. Capt.

Ordered me to stay with him, and I,

being nearly played out, do so. Get

a

little butter and milk from the house and stew some apples making a

nice,

refreshing supper.

Advance to Mountain beyond Middletown.

At foot of Mountain turned to the right, and along the

stream until we

came to a little

brick church. Turned

up the mountain. Left

knapsacks at a brick farm house. Johnny

Towne too sick to go further. Capt.

Ordered me to stay with him, and I,

being nearly played out, do so. Get

a

little butter and milk from the house and stew some apples making a

nice,

refreshing supper.

Monday September 15th

Capt. Fiske, [pictured,

Company G]

came to the

rear about midnight,

with “rheumatism in the

knees.” The 9th

fellows

hooted at him. He

wouldn’t let a man

fall out during the day, and was himself first out of sight of

danger.

Left Johnny and joined the

Co.

on the Mtn. in front of the Mtn Tavern. They had an

awful march getting

up last night, being

nearly worn out,

and quite a severe fight to face, too. They came up on the

extreme right

and had not so much

fighting to do as

the Penna. Reserves. A

great many rebels

are dead just back on the crest, and along the stone fence.

Flag of

truce just come in

this a.m. for body

of Gen. Garland. Gen.

Hooker received

them at the door of the tavern. Joe

Kelly captured a couple of woeful looking Johnnies, up in the rocks,

who are

afraid of being shot. Marched,

later in

the day, through Boonsborough, radiant with flags, to Keedysville,

where we lay

until after dark, when we crossed a bridge and lay on a high ridge near

a

mill. Co.

D. got into somebody’s pantry and spring house, as proved by the

quantity of

milk, butter, and preserves on hand.

The March to Keedysville; from "Three Years in the Army"

Monday,

Sept. 15.

Marched at daylight, two companies

being thrown out in front as skirmishers, until the top of the moutain

was reached, when we saw the enemy retreating toward

Boonsboro',

whereupon we started in chase, passing through that town to

Keedysville, about ten miles, without overtaking them. It is

not

without some truth they were called the "Fleetfooted Virginians."

The towns of Boonsboro' and Keedysville were decorated with Union flags, and it was inspiring to march through towns with Uncle Sam's bunting displayed, and listen to encouraging words from friends. This was our stamping ground of '61, and it seemed like home to us.

Short Summary of the Battle of Antietam

From "Three Years in the Army." Regiment Historian, Charles E. Davis, jr., gives a remarkably simple summary of the regiment's participation in the battle. Only the statistic at the end suggests the ferocity of the fight.

Tuesday, Sept. 16.

At 3:30 P.M. we moved across a bridge

toward the village of

Bakersville, on the Hagerstown and Sharpsburg turnpike, turning to the

left after crossing a country road, also leading to Sharpsburg, moving

parallel to it nearly half a mile under a heavy artillery fire from the

enemy. In order that their guns might have as little effect

as

possible we were formed "double column half distance" and march to the

front, then to the right, then front, then to the left, then front,

then

right again, then front, always preserving our formation, and

gaining to the front all the time. This movement made under a

heavy fire was performed with as much precision and coolness as though

the regiment was on a battalion drill. It is worth mentioning

to

show what good use may be made of the skill and confidence acquired by

constant drilling.

The Joseph Poffenberger Farm where elements of the First Corps, probably Meade's Division, bivouacked the night of September 16. Hartsuff's Brigade was camped a ways to the east of here, along the Smoketown Road. (View looking North).

Wednesday, Sept. 17.

It was a gray, misty morning,

and like the girl who was to be Queen of May, we were called early.

All night long the firing of guns on the picket line in front

of us disturbed our sleep, sounding very much like a "night before the

Fourth" at home. While we were endeavoring to see whether

the men moving in front of us were our own men or the rebels, an aid

from General Hooker's staff dashed up to where we stood, and, after

satisfying himself, ordered us to move. We went obliquely to

the right, across a fence, then across a lane and on to the corner of

the woods, from which we moved to the cornfield in front of the Dunker

Church. As we entered the corn-field we were received by a

sudden volley from the enemy, who, until that moment, were lying

concealed from view. Here we stayed until our ammuniton was

exhausted, when we were relieved and marched to the rear, where our

cartridge-boxes were replenished, and where we remained the rest of the

day. We took into this fight three hundred and one men and

brought out one hundred and sixty-five, a loss of forty-five per cent.

Another Account

The following

summary is from "Massachusetts in the War, 1861 - 1865" by

James Lorenzo Bowen, Springfield, MA; 1889.

The regiment was with its division in support and not actively engaged at the battle of South Mountain, September 14, but in the fierce battle of the Antietam, three days later, it had its full share. Near night of the 16th, Hooker's Corps crossed the creek and took position well up to the left of the Confederate line of battle, after some fighting in which the Thirteenth did not take part. Ricketts's Division had the left of the corps, and when the advance was made next morning Hartsuff's Brigade had the center of the division, with the other two brigades in echelon, the Thirteenth being the left center regiment.

The line advanced for some distance till it came under a heavy fire and was within a few hundred feet of the enemy when it opened fire and the action became deadly. The two right regiments of the brigade were after a stubborn contest obliged to fall back, having suffered severe loss; another regiment took their places and that in turn gave way. The regiment at the left, the Eighty-third New York, was also obliged to fall back, so that before the order came to the Thirteenth to retire it was left alone of the brigade line. The few hundred men that remained of the division were reformed and placed in line, ready to respond to any call which might be made upon them, but they were not again sent into the fight. The loss of the Thirteenth Regiment during the two hours or less that it had been engaged reached 139, of whom 15 were killed, 120 wounded and four missing.*

*Note: The full casualty report is listed below. The revised number of killed is 26.

George W. Smalley's Report of the Battle

The Battle of Sharpsburg from the extreme Right. Sketched by A.R. Waud. Inscribed upper left: Mansfield; Williams; Green; Lt. Col. Knipe; Early; Inscribed within the image as indicators, Best's Battery 4th Maine; 16th Indiana; Gen Mansfield and staff in here; 3rd Wisconsin; Col. Ruger wounded; 43rd N.Y. laying on the ground. [Col. Ruger was in Gordon's Brigade.]

Intrepid New York Tribune War Correspondent George W. Smalley was acting aide to General Hooker during the fight. He wrote a vivid account of the early morning battle, and gave prominent mention to Hartsuff's Brigade in his report. But he attributed the brigade to Doubleday's Division which throws doubt on the story. John S. Fay and Warren Freeman quote the story in their memoirs. In the case of Freeman, it was in a letter home soon after the battle. Thirteenth Mass. Historian Charles E. Davis, Jr. was aware of the discrepency and addressed it at some length in his book, "Three Years with the Army," published in 1894. Davis sites a letter in the National Tribune, March 24, 1892 from General Abner Doubleday regarding Smalley's report.

Editor National Tribune, - A very interesting article appeared in your paper a few weeks ago in reference to the battle of Antietam. It is in the main accurate, but contains one error which I desire to correct, and which would seem to have originated in the correspondent of the New York "Times." After three hours' fighting, at a crisis in the battle when it became doubtful if we could hold the bloody cornfield between the lines, Hooker, it is alleged, sent word to Doubleday, "send me your best brigade." It stated that this "best brigade" went forward and held the field, which, however, was lost later in the day.

Now, as my division began the battle in the morning, and was the first to charge the enemy, I had no brigade to spare, for three of mine under Gibbon, Patrick, and Phelps, were already closely engaged at the front. They had lost heavily, and captured six battle-flags, were out of ammunition, and in obedience of an order from General Hooker were holding the position with the bayonet. I had another brigade, it is true, under the gallant Hoffman, but it was kept in rear by a special order from General Hooker, in consequence of a slight demostration made by Stuart's cavalry on that flank. It was Hartsuff's brigade, of Ricketts' division, that held the cornfield so handsomely, and not one of mine. Ricketts was entitled, I thought, to a good deal of credit for the way in which he handled his men; but through some misrepresentation or misunderstanding he was relieved from command at the close of the day by General McClellan, and his division was turned over to General Gibbon.

Brevet

Major-General, U.S.A.

Still, Author, Stephen W. Sears assigns credit to the brigade mentioned by Smalley to Brig.-General George H. Gordon of Mansfield's 12th Corps, which arrived on the field after Hartsuff's Brigade left.

Here is Smalley's Report as quoted in "Three Years in the Army." [George Washburn Smalley, pictured].

The

battle began with the dawn. Morning

found both

armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each

other's eyes. The left of Meade's reserves and the right of

Ricketts' line became engaged at nearly the same moment, one with

artillery, the other with infantry. A battery was almost

immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a ploughed

field, near the top of the slope where the cornfield began.

On

this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods which stretched

forward into the broad fields, like a promontory into the ocean, were

the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day.

The

battle began with the dawn. Morning

found both

armies just as they had slept, almost close enough to look into each

other's eyes. The left of Meade's reserves and the right of

Ricketts' line became engaged at nearly the same moment, one with

artillery, the other with infantry. A battery was almost

immediately pushed forward beyond the central woods, over a ploughed

field, near the top of the slope where the cornfield began.

On

this open field, in the corn beyond, and in the woods which stretched

forward into the broad fields, like a promontory into the ocean, were

the hardest and deadliest struggles of the day.

For half an hour after the battle had grown to its full strength, the line of fire extended neither way. Hooker's men were fully up to their work. They saw their general everywhere in front, never away from the fire; and all the troops believed in their commander, and fought with a will. Two-thirds of them were the same men who, under McDowell, had broken at Manassas.

The half-hour passed; the rebels began to give way a little, - only a little; but at the first indication of a receding fire, "Forward!" was the word, and on went the line with a rush. Back across the wood, and then back again into the dark woods, which closed around them, went the retreating rebels.But out of those gloomy woods came suddnly and heavily terrible volleys - volleys which smote, and bent, and broke, in a moment, that eager front, and hurled them swiftly back for half the distance they had won. Not swiftly nor in panic, any further. Closing up their shattered lines, they came slowly away; a regiment where a brigade had been; hardly a brigade where a whole division had been victorious. They had met at the woods the first volleys of musketry from fresh troops - had met them and returned them till their line had yielded and gone down before this weight of fire, and till their ammuniton was exhausted.

In ten minutes the fortunes of the day seemed to have changed; it was the rebels who were now advancing, pouring out of the woods in endless lines, sweeping through the conrfield from which their comrades had just fled. Hooker sent in his nearest brigade to meet them, but it could not do the work. He called for another. There was nothing close enough, unless he took it from his right. His right might be in danger if it was weakened; but his centre was already threatened with annihilation. Not hesitating one moment, he sent to Doubleday, "Give me your best brigade instantly."

The best brigade came down the hill to the right on the run, went through the timber in front, through a storm of shot and bursting shell, and crashing limbs, over the open field beyond, and straight into the cornfield, passing, as they went, the fragment of those brigades shatterd by the rebel fire, and streaming to the rear. They passed by Hooker, whose eyes lighted as he saw these veteran troops led by a soldier whom he knew he could trust. "I think they will hold it," he said.

General Hartsuff took his troops very steadily, but, now that they were under fire, not hurriedly, up the hill from which the cornfield begins to descend, and formed them on the crest. Not a man who was not in full view - not one who bent before the storm. Firing at first in volleys, they fired then at will with wonderful rapidity and effect. The whole line crowned the hill, and stood out darkly against the sky, but lighted and shrouded ever in flame in smoke.They were the Twelfth and Thirteenth Massachusetts, the Ninth New York, and the Eleveth Pennsylvania - old troops, all of them.

Then for half an hour they held the ridge, unyielding in purpose, exhaustless in courage. There were gaps in the line, but it nowhere bent. Their general was severely wounded early in the fight, but they fought on. Their supports did not come - they determined without them. They began to go down the hill and into the corn; they did not stop to think that their ammuniton was nearly gone; they were there to win that field, and they won it. The rebel line for the second time fled through the corn and into the woods. I cannot tell how few of Hartsuff's brigade were left when the work was done. There was no more gallant, determined, heroic fighting in all this desperatae day. General Hartsuff is servely wounded; but I do not believe he counts his success dearly purchased.Davis states that Alfred C. Monroe, of the Twelfth Masachusetts, at the time of the battle, attached to General Hooker's headquarters, says he heard the order given as Smalley relates it. According to battlefield maps from the Antietam Library, Hartsuff's 3rd Brigade advanced to the cornfield at 6:20 a.m. after Duryea's 1st Brigade had been battling the rebels alone for about 1/2 an hour. They made a heroic stand between 6:20 and 7 a.m. Between 7 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. Hartsuff's Brigade fell back to the north. Gordon's Brigade advanced to the same spot between 7:30 and 8:00 a.m. It is disappointing to cast doubt on such a glowing report of Hartsuff's Brigade at Antietam, but I felt it necessary to inform readers that the question exists.

In a letter to Col. John M. Gould*, written April 20, 1894, Sgt. Robert B. Henderson of the 13th Mass., wrote: "As for Smalley’s account, I have of course always known it to be not correct as to its details. I can only account for his story in some such way as this. (For I don’t desire to charge him with deliberately manufacturing a lie). But we were very heavily engaged, and the enemy were with a heavy force of infantry and Artillery with grape and canister falling back very slowly and with firm resistance. I can imagine that when some officer may have expressed some doubt as to the outcome, Gen. Hooker may have said “one of my best brigades is there”.

*Historian John Gould, was researching the fight in the East Woods and the death of Genral Mansfield at the battle of Antietam.

The Memoirs of John Sawyer Fay

Sergeant

John Sawyer Fay of Company F, was severely wounded during the

Chancellorseville Campaign of 1863. Fay was struck by a shell

that killed two others. Sergeant Enoch C. Pierce tied a

tourniquet around Fay's shattered leg and rushed him to the field

hospital. Thirteenth Mass. Surgeon, Allston W. Whitney,

operated and saved Fay's life, but it cost John his right arm and

leg. Soon after, the field hospital was captured by the

advancing

Rebel Army and both men were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, VA.

Fay survived the ghastly journey and several weeks

imprisonment

at

Libby. He was parolled and brought to Annapolis, MD to begin

his

long recovery. This story will be told at another time on

this

website. I recieved this unpublished remembrance of the

Battle

of Antietam from one of Fay's many descendants.

Sergeant

John Sawyer Fay of Company F, was severely wounded during the

Chancellorseville Campaign of 1863. Fay was struck by a shell

that killed two others. Sergeant Enoch C. Pierce tied a

tourniquet around Fay's shattered leg and rushed him to the field

hospital. Thirteenth Mass. Surgeon, Allston W. Whitney,

operated and saved Fay's life, but it cost John his right arm and

leg. Soon after, the field hospital was captured by the

advancing

Rebel Army and both men were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, VA.

Fay survived the ghastly journey and several weeks

imprisonment

at

Libby. He was parolled and brought to Annapolis, MD to begin

his

long recovery. This story will be told at another time on

this

website. I recieved this unpublished remembrance of the

Battle

of Antietam from one of Fay's many descendants.

Fay's account quotes liberally from War Correspondent George Smalley's report for the NY Tribune.

A writer in The Worlds Work for March 1904 says, “Every man in the Northern and Western States who is old enough to remember the civil war must often be surprised at the ignorance of the two generations, younger than he, about even the principal facts of the conflict".The writer goes on to say, "There is much less popular knowledge of the civil war than of the war of the Revolution. This fact is not an accident, it is a striking proof, that the war was the end of an epoch rather than the beginning of one; that it closed a series of events and ended a long controversy and that subsequent generations have thanked Heaven that it was passed before their period of activity began. Even the great actors in it, except the few greatest, have practically been forgotten.

‘It is passing out of the minds of most people, less than forty-five years of age - or would pass out - if the old survivors would keep quiet and permit them to forget it".

From your association with the veterans of the Civil War, you may think that about all they had to do in the army was to sit around a campfire and smoke.

I shall briefly try to show you that all the smoke made in the army by the old soldier was not caused by burning tobacco.

It is true the best soldiers were those who would cheerfully accept any situation in which their duty placed them so that they could get all the comfort possible as they went along.

A soldier in the ranks during a battle can see but little that is going on about him except on rare occasions. He is but a cog in one of the many wheels composing that vast machine, an army. He must fill the position in which he is placed without questioning. Yet the more intelligent the soldier in the ranks, the better the army. Like all other positions in which man is placed, the more intelligent he is the better he will perform his duties; the more valuable he will be to the cause in which he is engaged.

The Regiment in which I served has the meritorious record of having the smallest number of deaths from disease of any regiment in the Union Army. This was due mainly to their habits of cleanliness. The men were intelligent enough to appreciate and understand the necessity of faithfully obeying orders of our officers, particularly of our Surgeon, in regard to keeping ourselves and our camp as clean as possible, which was not an easy duty, for our camps were often pitched in swampy places where it was difficult to find a dry spot on which to spread our blankets.

In most wars more men die or are disabled from disease contracted in the army than are killed or disabled in battle. It was so in our Civil War.

The battle of Antietam was the greatest slaughter of human life in the world's history in same length of time considering the numbers engaged. The battle only lasted about 10 hours. There was actually engaged only-about 60,000 Union troops and 50,000 Rebel.

McClellan had about 27,000 men; Fitzjohn Porter’s Corps held in reserve; they did not fire a gun that day. The Union killed and wounded were 11,657. The Rebel loss must have been more for he left according to Gen. McClellan's report 2,700 dead, unburied on the field.

The Rebel Gen. Lee reports that he had 7,816 wounded, making his loss at least 10516 and good judges estimate that his killed and wounded were at least 1,000 more, so there is no doubt that the total of killed and wounded on both sides was at least 23,173.

In other battles of the Rebellion like Gettysburg, the loss was greater, but there were more troops engaged and the battle extended over three days.

I propose to describe what I saw and the part our Brigade took in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. My regiment was the 13th Mass. We were in the third Brigade, second division, first Corp. Our Brigade was composed of the 12th and 13th Mass 11th Penn. and 9th New York Regiments. We had served together for many months. The Regiments were all acquainted with each other. We had been through several battles together and we knew by experience that each would stand by the other.

Our Brigade was commanded by Gen Hartsuff. A more skillful or a braver man I never saw. He was a West Point graduate, a strict disciplinarian, but kind to his men and we had the utmost confidence in him. Our Division was commanded by Gen Ricketts and our Corp by Gen Hooker. The latter took command of our Corp immediately after the Second Bull Run battle where we were badly defeated on Aug 29 and 30.

The battle of South Mountain commenced on Sept 14,1862 when our army met the rebel forces at Turners Gap west of Frederick City, Md.

On the night of Sept l3 our Brigade bivouacked in the outskirts of the city which on that day had been evacuated by the rebels. This was the day that was preceded by that “Cool September morn” described by the poet Whittier in his poem on Barbara Freitchie. It was on the 13th day of Sept. that the loyal old lady waved from her window the Stars and Stripes in the face of the retreating rebel hordes as they marched through the city.

On the morning of the 14th we were marched into the city. Our Regiment was some acquainted in the town for we had camped within their borders the year before, but we were not allowed to stop to renew old acquaintances but were hurried through the city to the West, out through the town of Middleton on to the national turn-pike that passed over South Mountain through Turners Gap. About noon we were halted beside the road at the foot of the mountain. While we were resting there, Gen McClellan rode by; this was my first view of the then famous General. He was received with much enthusiasm as he rode by our Corp.

The rebels had fortified the pass and had a strong force entrenched on the slopes commanding the road through Turners Gap. They also had troops posted on the summit both sides of the Gap. The battle commenced soon after noon by the advance of our left under Gen Reno who moved his troops up the slope on the south side of the road. It was here that the brave General was killed. Soon after the battle commenced on the left, our Brigade was filled out on north side of the road and commenced to climb up the rocky sides of the mountain. The ascent was so steep in places we had to push and pull each other up. We soon encountered the rebel picket line who kept up a plunging fire at us, but we were so far below that most of their shots passed over our heads.

We kept steadily but slowly advancing, their picket line retreating. The ground was rocky and steep; we could not advance as rapidly as our General wanted. We understood that Gen Hooker was making one of his famous flank movements. All this time while we were crawling up the steep mountain side heavy firing could be heard way down on our left indicating that a severe engagement was taking place.

Gen Hartsuff told us if we could reach the summit before dark he hoped to swing around and take the rebel force that was opposing Gen Reno in flank and rear. But it was a hard road to travel. It was nearly dark when we reached the summit very much exhausted. We were immediately reformed and changed direction to the left and commenced to move in direction to strike the enemy on their left flank and rear, but they hastily retreated before we could get into position to do them much injury. Their retreat opened the road through the pass for our army to advance. We lay on our arms in line of battle all night. We were not allowed to build a fire to cook coffee or to keep warm.

At daylight on Sept. 15 we were advanced down the western slope of the mountain. Soon we emerged from the woods where we could obtain a view of the valley below where we saw the rebel army, in full retreat on the road through Boonsboro some four or five miles distant.

As we marched down the slope, we had to halt several times to remove the dead bodies of the rebels from the road, as in places they were so thick we could not get along without stepping on them.

We were halted near the Summit House for a rest and to cook our breakfast, while fresh troops followed up the retreating rebels.

While we were resting here Comrade C. E. Haynes and myself went down back of the Summit House into a field that looked as tho we might find some new potatoes. When we got into the field we saw in a piece of woods on the edge of it, a squad of five rebel soldiers guarding a pile of knapsacks. We inquired to know what they were doing. They replied that they were ordered to guard those knapsacks until they were relieved. We asked them if they knew their army had retreated. They replied that they did; they stayed so as to be captured; they had rather be prisoners in our hands than fighting in the ranks of the rebel army.

We marched them up into our camp and turned them over to the provost marshal. Among the knapsacks that they were guarding was some that belonged to our regiment which had been captured from us three weeks before at Bull Run but I did not find mine among them.

A staff officer of

McClellan’s, Col D. H. Strother (pictured)

was in a position to

witness our advance. He describes it as follows.

A staff officer of

McClellan’s, Col D. H. Strother (pictured)

was in a position to

witness our advance. He describes it as follows.

"Hooker"s column was seen crawling up the rocky and difficult ascent on the right, slowly trailing across the open ground, now entering a piece of wood and again emerging on the upper side, winding over spurs and ravines; the march resembled the course of a huge black serpent with glittering scales, stealing upon its prey.

“At length we had a glimpse of Hooker’s Command in some open ground on the summit, moving in column of Companies, and heading towards the Gap. They presently disappeared in the wood and then came the distinct muttering of musketry which continued with little intermission until after dark and always approaching the Gap.

“As Hooker moved from his position on the right we could discern a dense and continuous column of the enemy moving to meet him not far from the national turnpike at the Summit House”.

The next morning Sept. l5, the

same staff officer rode over the field

and described the scene as follows.

“On the summit and slope beyond, the earth was thickly strewn with the rebel dead who lay as they fell, in all their squalor and hideous distortions; numbers of them lay in the laurel thicket half hidden among the blood stained leaves. Near a cabin riddled with musket balls, we saw the lane formed by parallel stonewalls which had served the enemy as a rampart. It had been cleared of the dead to admit the passage of our troops, and the bodies lay on either side as high as the walls. In the bushes near by were many still living but too far gone to bear moving."

Confederate Dead at Fox's Gap; September 15, 1862 after an eyewitness sketch by James E. Taylor inscribed "On the Mountain Top Cross Roads Day after Reno's Fight." Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. II - p.583.

After we had our breakfast and a rest near the Summit House, we were started out on the road over which the rebels had retreated, on through Boonsboro to Keedysville. Along the road was evidence of their hasty retreat in broken-down wagons, dead mules, crippled caissons, houses filled with wounded, and the road strewed with muskets, knapsacks and butternut jackets.

We reached Keedysville, ten miles distant from the Summit House, about three o’clock in the afternoon without overtaking the rebel army, they having retreated across the Antietam creek and were forming their lines of battle with that stream in their front.

We camped here until the afternoon of Sept.16. During all of Sept.15 and until afternoon of the 16th there was no indication that Gen. McClellan had attempted to attack them. The rebels during this time were getting into a splendid position for them on ground between the Potomac river and Antietam creek which is described by Col. Palfry as follows.

“Between Mercerville on the

north and the confluence of the Antietam on

the south, a distance of about six miles in a straight

line, the Potomac follows a series of remarkable curves, but

its

general course is such that a line of battle something less than six

miles long may be drawn-from a point a little below Mercerville to a

point a little above the mouth of the Antietam so as to rest both of

its flanks upon the Potomac to cover the Shepherdstown Ford and the

town of Sharpsburg and to have

its

front covered by Antietam Creek."

The Antietam creek is crossed by three bridges over that portion of the stream in front of Lee's lines. The bridge nearest to its confluence with the Potomac was not used during the battle except by the rebel Gen. A. P. Hill's troops coming from Harpers Ferry to re-enforce Lee. The next bridge is known as the Burnside Bridge. It is that by which the road from Sharpsburg to Rohrersville crosses the stream. The next is the bridge of the Sharpsburg, Keedysville and Boonsboro turnpike. This is the one over which the rebels retreated from South Mountain and over which the right wing of our army crossed on the afternoon of Sept.16. The stream is sluggish and winding and tho it has several fords they are difficult. (pictured is the Upper Bridge, view from the northwest).

In the rear of Sharpsburg is a good road to the Shepherdstown Ford across the Potomac into Virginia. Besides the roads already mentioned, an important turnpike leads northward from Sharpsburg to Hagerstown on the western side of the Antietam (that is the side occupied by Lee's army.)

The ground occupied by Lee rises in a slope of woods and fields to somewhat of a bold crest and then falls away to the Potomac. In this strong position Lee proceeded to form his lines and Gen. McClellan was accommodating enough to give him all of Sept.15 and until the afternoon of the 16th in which to do it unmolested.

About three o'clock in the afternoon of Sept.16 we were marched across the bridge on the turnpike from Sharpsburg to Keedysville towards the Hagerstown pike, turning to the left after crossing a country road also leading to Sharpsburg and moving parallel with it for nearly a mile, under a heavy fire from the enemy.

Hooker was forming the first Corps on our extreme right so as to strike the rebels left where it was not protected by the stream. In order that their shelling might have as little effect as possible we were formed in double column half distance and marched to the front then to the right, then front, then to the left, then front, then right again, then front, always preserving our formation and gaining to the front all of the time.

The ground over which we

advanced was much broken by small

hills and

ravines. Gen. Hartsuff, who was an artillery officer in the

regular army before the war, showed his skill as a trained officer in

that branch of the service in the masterly way he advanced us in the

face of that heavy artillery fire with so little loss.

Our Brigade had so much confidence in him, they moved with as much precision and coolness as tho the regiments were on battalion drill. We were halted after dark for the night in the edge of a grove of scattering trees. In front of us was an open field from whence issued heavy musketry fire. We lay in line of battle all night with our picket line only a few yards in front of us. As night came on, the firing from both armies nearly ceased, only a scattering fire was kept up on the picket line. Gen. Hartsuff lay down behind a large tree just in the rear of our company. We were the Color Company of our Regiment. About midnight we were aroused by a volley of musketry fired in our front which was immediately answered by a second volley. Then stillness reigned.

I heard Gen. Hartsuff ask "What's that Joe." and to our surprise Gen. Joseph Hooker replied, "Rebels shooting each other. We have no troops in there." That was the first we knew that Gen. Hooker was bivouacking with our Brigade. It appeared as tho two brigades of rebels while moving in the darkness mistook each other for Union troops. (Major-General Joseph Hooker, pictured).

Towards morning I obtained a little sleep. I remember I was awakened by a branch of a tree falling upon me, it having been cut from near the top of a tree under which I was sleeping, by a rebel shell.

They commenced the battle by opening on us with their artillery before it was fairly daylight on Sept. l7. It was a cool gray foggy morning. While we were endeavoring to see whether the men in our front were our men or the rebels, an officer from Gen. Hooker's staff dashed up to where we stood and after satisfying himself, ordered us to advance.

We moved obliquely to the right, across a fence, then across a lane and cut to the corner of a piece of woods near the house of Joseph Poffenberger. Here we held our position for about half an hour. We were having comparatively an easy time. From our partially sheltered position evidently we were doing good execution with small loss to ourselves. We could see that out on our left our forces were having much harder fighting than we were. We saw our line charge but they seemed to have but little effect, for the rebels would return with a charge and drive our forces back. I thought we were very fortunate in being placed in such a sheltered position. I never saw our regiment so cool when under fire.

This is a view looking to the south; the route Hartsuff's Brigade took to the cornfield which would be up front in the distance. The Joseph Poffenberger farmhouse and barn are behind the viewer some distance to the right. The East Woods are up ahead on the left. Of course there wasn't snow on the ground. This photo taken, March, 2005.

They fired as deliberately as tho they were on target practice, but our self congratulations were of short duration, for suddenly we were ordered to move by the left flank for a short distance towards the part of the line where we had seen those desperate charges. Then by front, then left oblique, through a small piece of woods in which the shells from the rebel artillery were rattling like hail in a thunder storm, up a small hill into a field of standing corn in front of Dunker church. While making this advance, the shattered regiments of three brigades passed through our line on their way to the rear. When we arrived at the crest of the hill from which the cornfield begins to descend, we were met by a sudden volley from a division or a brigade that far out-numbered us, who until this moment were lying concealed from view.

They fired too high. We replied with a volley that I am satisfied was far more effective. We held this position, firing at will as rapidly as we could for about half an hour, when seemingly from a common impulse, for none of us remember hearing an order, we advanced down the hill through the cornfield and obtained a position in the edge of a grove of large scattering trees; in our front was an open field.

This is a view from the corner of the East Woods looking toward the Rebel Position. The Cornfield was directly to the right, the plowed field. across the fence just in front. The farm buildings on the hill in the distance are behind what was the Rebel position. Those buildings were not present at the time of the battle. Photo taken, March, 2005.

The enemy were formed in a sunken road in our front about an eighth of a mile from us. We used the large trees for shelter as much as we could and kept up a steady fire that I know was very effective. At times the smoke and dust was so thick, we could not see the enemy when we would cease firing until it cleared so that we could see something to fire at. Three times they charged under cover of the smoke, across the open field. Every time we repulsed them, tho they outnumbered us two to one. We were losing heavily but the trees afforded us some protection. Our ammunition was getting low. We used all we could find in the boxes of our dead and wounded comrades.

I remember James L. Stone throwing his belt and cartridge box at my feet as he crawled to the rear after receiving a severe wound in the thigh.

We kept ourselves covered as much as possible behind the trees and stumps. Sergt. James H. Belser and myself were behind a tree. Belser was a better marksman than I was. I suggested that I would load for him to fire which he did with good effect.

During a lull in our firing, because the smoke was so thick, we were startled by a shot coming from a point well on our left. In a few minutes some one, I think it was Sergt. Pierce, exclaimed, "There he is behind that mound”, which was evidently made by a tree having been blown over. We fired several shots at him but could not hit him. Belser suggested if some one could get behind a large stump some distance out in our front he might be dislodged. Corp. Bridgewater started to go; Pierce stopped him as he was not a good shot. Pierce said he would go himself.

(Sergeant Enoch C. Pierce, Company F, pictured, below right). Belser says, No if several of you would fire at the reb, one at a time so as to keep him behind his cover, he Belser, would make for the stump. We did so and Belser got a position safely behind the stump. The reb soon discovered Belser. After trying for several minutes to get a bead on each other, Belser held up his cap on a stick. The reb shot the cap and Belser shot the reb and got safely back to our line.

The

next day Belser found the

rebel dead behind the mound. He

belonged to a Georgia regiment and was armed with an Enfield rifle like

those we carried. Belser took the rifle and carried it until

he was promoted to a Lieut.

The

next day Belser found the

rebel dead behind the mound. He

belonged to a Georgia regiment and was armed with an Enfield rifle like

those we carried. Belser took the rifle and carried it until

he was promoted to a Lieut.

Our Corp. Commander Gen. Hooker and our brigade Commander, Gen. Hartsuff were both wounded. We had been fiercely engaged for nearly three hours and had been constantly in line of battle and under fire for eighteen hours with no opportunity for rest or to cook our food. Nearly one half of our regiment were killed or wounded. The other regiments in our brigade had lost as heavily.

The enemy had been re-enforced and were preparing to make another charge. Our ammunition was exhausted. We could do no more so were ordered to the rear. As we turned to retreat, we found fresh troops in line of battle just in our rear ready to receive the charge the rebels were about to make. As we went to the rear we helped off what wounded we could.

While helping a comrade to the

rear we passed four men who were

carrying a wounded man on a stretcher. I thought it was

Sergt. Pierce

of my company. After getting the men that I was helping to a

safe

place I hastened back to help those who were carrying the

stretcher. Some of them had been disabled so they were

obliged to lay their burden down in a very exposed position where the

rebel bullets were flying thickly around, when I reached them.

I found that the man on the stretcher was not Sergt. Peirce but Lieut. Abel H. Pope (pictured, left) who entered the service as first Lieut. of my company but who on that day was in command of Co. D. I helped to carry him back to a field hospital. He was badly wounded and so weak from the loss of blood I thought he was dying. He partially recovered and in due time reached his home in Hudson but died soon after the war closed.