The Battle of the Wilderness

PART 1: May 4th & 5th, 1864

Saunders Field, from the Confederate position, captured by the incomparable photographer, Buddy Secor.

Table of Contents

- Introduction –– Whats On This Page

- Essay: What, What Is Wrong With The Army Of The Potomac?

- May 4th, 1864: The River Crossing

- Captain Ludington and the Wagon Train

- Leonard's & Baxter's Brigades on the March

- Commentary

- Essay: Lost in the Wilderness; Finding the 13th MA on May 5th

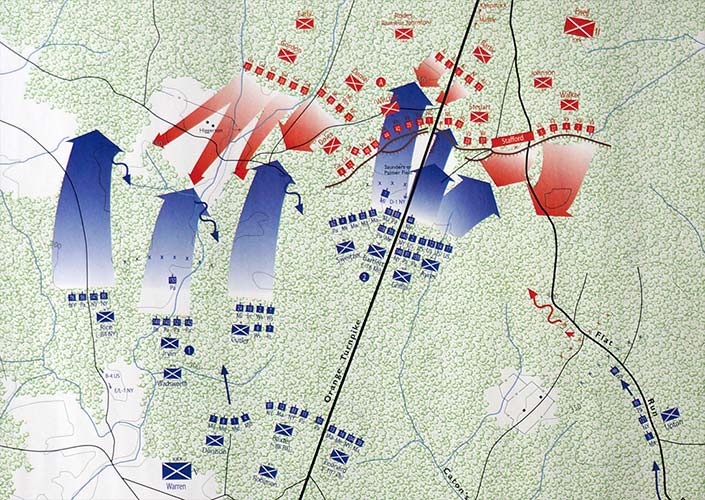

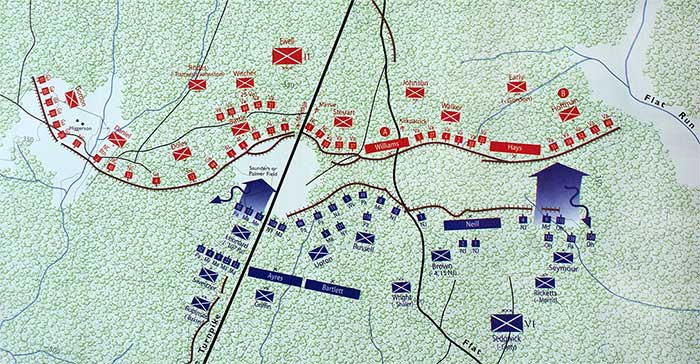

- The Battle May 5th 1864: The 5th Corps Caught Unawares

- Colonel Leonard's Brigade at the Battle, May 5th

Introduction –– Whats On This PageGreetings. This page has been a long time in the making. The initial sources I had in my library did not clearly explain the role the “13th Mass” played in the battle on May 5th, 1864. The next day's position was easier to figure out. In particular I had questions about the regiment's position on the battlefield around Saunders Field after they crossed the Orange Turnpike to the South side of the road mid-afternoon. I needed more sources to solve the riddle if I could find them. One resource I knew of, but hadn't yet obtained was in the Boston Public Library Special Collections Department. Upon discovering they now offer scanning services, I requested and received copies of Private Bourne Spooner’s journal, (September 1863 — Post War). Remarkably, Private Spooner's journal contained a comprehensive account of events during the battle on May 5th; precisely the information I was seeking. Once transcribed, anomalies in other accounts fell into place. I was able to complete the page. There were still problems and puzzles to be solved in the narratives of the 13th MA veterans, but these are discussed in the mid-page essay, “Lost in the Wilderness.”

The Battle of the Wilderness was a stalemate, but it shouldn't have been. That could be said of many battles fought by the Army of the Potomac. This page starts off with a look at some of the more glaring errors committed on May 4th & 5th by the commanders of that army. An essay on this page explores this subject. It is titled, “What, What Is Wrong With The Army Of The Potomac?” ––A rhetorical question found in author Morris Schaff's somewhat philosophical book, “The Battle Of The Wilderness.” The next section on this page is titled, “March 4th 1864; The River Crossing.” The most descriptive accounts available from the 13th MA, the 39th MA, and Col. Charles Wainwright of the 5th Corps Artillery detail the march across the Rapidan. These sources, along with Major Abner Small of the 16th Maine, are the primary narrators throughout the page. Time out is taken in the middle of this narrative to relate a humorous episode that occurred on the day of the march, which highlights General George Gordon Meade’s notorious temper. The episode is titled, “Captain Ludington and the Wagon Train.” Following the general narrative of the march, is a section of observations directly related to Colonel Leonard’s brigade. A couple references about the march of Baxter’s Brigade of the same division are also included. A 3rd Brigade of Marylanders, commanded by Colonel Andrew W. Denison, was added to General John C. Robinson’s 2nd Division during the army re-organization in March, but I have not chronicled their experiences in the battle. Their association with the division is only just beginning, whereas the regiments in Baxter's Brigade have a long connection with the 13th Massachusetts. The long essay detailing the part the 13th Massachusetts played in the battle May 5th, is next. It is titled “Lost in the Wilderness; Finding the 13th MA on May 5th.” I found the primary source material full of puzzles when I initially laid out this web-page. I have tried to clarify the regiment's movements and changes of position as accurately as possible, ––hence the lengthy essay. Memoirs and diary entries are quoted here in part, as needed. The complete quotes and narratives are posted in their entirety later on the page. I apologize that its a bit redundant, but done this way gives context to the reminiscences. One exception is Corporal George Henry Hill’s memoir titled, “Reminiscences From The Sands Of Time.” Only the excerpts from that memoir, that are relevant to the discussion of the regiment's whereabouts May 5th, appear on this page. The entire memoir in all its great length and detail will be posted on a separate page later. It is hoped this section will give readers a good understanding of what the regiment did during the battle on May 5th. Particularly if they have also read the first essay at the top of the page, that addresses certain campaign errors. The next section, titled, “The 5th Corps Caught Unawares,” is the general story of the day’s battle around Saunders Field. Photographs, and resources from the Wilderness Battlefield National Park, along with various soldier accounts found in books and histories are used to reveal the action. Its a broader picture of the fighting along the Orange Turnpike sector of the battlefield. The last section on this page, is titled, “Colonel Leonard’s Brigade at the Battle.” Here is a re-posting of the complete entries of the soldiers' diaries and memoirs in my collection, cited in the previous essay. Bourne Spooner’s reminiscence is a highlight. Readers of this page won’t come away with a detailed description of the heaviest fighting, nor any of the fighting that occurred along the Orange Plank Road to the South. But it is hoped a general knowledge of events around Saunders Field and a better knowlege of the part played by the 13th Regiment, will be understood as opposed to what was written in their regimental history. One last thing ––my notes & comments to the text throughout this page are bracketed and italicized, and signed "B.F." Acknowledgments I want to

thank Retired National Park Historian Greg

Mertz for indulging my theories about the movements of Leonard’s

Brigade on May 5th. The page is dedicated to Mr. Eric Locher, (step-relation to Lt. William R. Warner of the 13th MA) because, he listens with interest. Special Bibliography The following texts were used in researching the battle. These are additional to the usual sources I quote on this site, and on this page, such as the histories of the 13th MA, 39th MA, 16th ME, and 9th N.Y.S.M. etc. Billings, John D.; “Hard

Tack And Coffee,”

Boston, 1887. [Collector’s Library of the CW; 1981.] DIGITAL SOURCES Bicknell, George W., Rev. “History

of the Fifth Regiment Maine Volunteers,” Published by Hall L.

Davis,

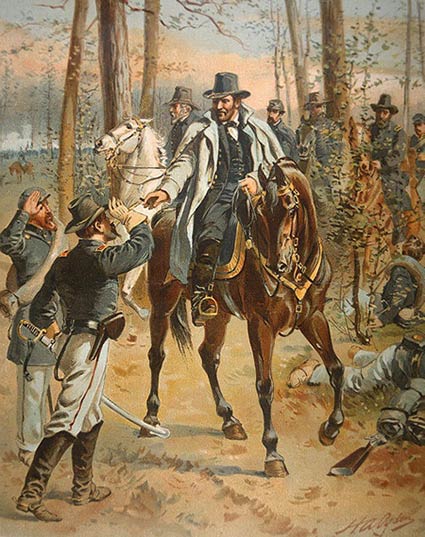

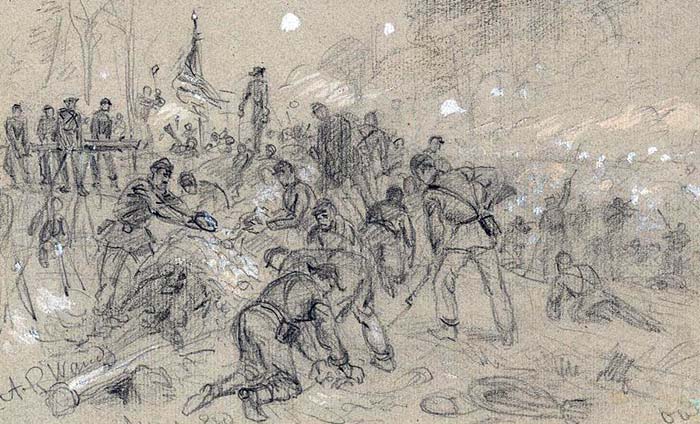

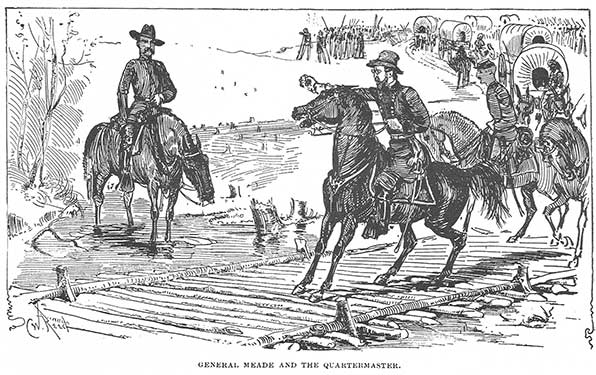

1871. PICTURE CREDITS: All Images are from the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS DIGITAL COLLECTIONS with the following exceptions: The banner image of Saunders Field is by photographer Buddy Secor; General Grant in the Wilderness Campaign by H. A. Ogden from Art.com; The photo of Robinson's Tavern was taken in 1910 by Ralph Happel, Chief Historian at the National Park Service Headquarters, Fredericksburg; Portrait Joseph Bartlett, Jacob D. Sweitzer, Major Madison Burt, Major James A. Cunningham & Col. William S. Tilton are from U.S. Army Heritage Education Center, Carlisle, PA Massachusetts MOLLUS Collection; Portrait of General G. K. Warren from the Civil War Artifacts Dealer, Horse Soldier; Portrait of Morris Schaff is from Wikipedia; Illustration of the overturned mule is from Civil War Times Illustrated Magazine, Number 4, (July 1962) "The Army Mule, carrier of Victory by Warren Lee Gross; Historic Picture of Ellwood taken from the site of the Wilderness Tavern, is from National Park Service interpretive marker onsite at Ellwood; Portrait of Major Abner Small is from Maine History (website); The three illustrations: “Union Troops Crossing the River,” [by Edwin Forbes] “Headquarters at Brandy Station,” [from a photograph] & Distributing Ammunition” are from Battles & Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 4; The Century Company, 1888; “General Meade and the Quartermaster,” by Charles H. Reed is from "Hardtack & Coffee," by John D. Billings; Portrait of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman is from the Internet Archive from , "Meade's Headquarters, 1863-1865," Boston, 1922; Portrait of Captain Amos M. Judson, is from Hagen History Center, Erie Pennsylvania; Portrait and sketch by Austin Stearns from his memoir, “Three Years With Company K,” by Sergeant Austin C. Stearns, (deceased) Edited by Arthur Kent; Associated University Press, 1976.; Portrait of Sam Webster from the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; Portrait of John Best and George H. Hill provided by family descendants, Author's collection; Portrait of Theodore H. Goodnow from Findagrave Memorial, posted by Matthew Sargent; Portrait of Herbert A. Reed from Digital Commonwealth at: https://www.digitalcommonwealth.or; Portrait of Elliot C. Pierce, is from a photo taken of the image belonging to collector friend, Joseph Maghe. Digital photos taken by the author, Bradley M. Forbush. Other images as cited with captions. ALL IMAGES HAVE BEEN EDITED IN PHOTOSHOP. Essay: What, What Is Wrong With The Army Of The Potomac?(Title from a rhetorical question asked in Morris Schaff's book, “The Battle of the Wilderness.”) Some Union Errors in the Campaign.

At one a.m., May 4th 1864, in the wee hours of the night the Army of the Potomac stepped off on a new campaign. Spirits were high. The air was filled with excitement that naturally accompanied a grand move of such a large army setting out on a fresh campaign. The troops were well rested, re-organized and recruited to a strength of nearly 102,000 men. From the few glimpses of General Grant the men had caught during the months of March and April, the new commander of all the armies seemed to be a determined man, with a string of victories to back him up. Many hoped that this campaign would bring the bloody war to a close. There were reasons to be hopeful. Notwithstanding, seasoned veterans were more cautious. They would wait and see before passing judgement on General Grant’s abilities. The same high morale had existed in the Army of the Potomac exactly one year earlier, in May, 1863, when General Joseph Hooker launched his Spring campaign. Hooker had likewise revitalized the army during the winter encampment of 1863, after the debacle of General Burnside’s tenure in command. But Hooker's campaign which began with great promise, ended in defeat. By comparison, how would General Grant perform? The new commander of all the armies considered the advance on May 4th a great success. The army crossed the Rapidan River, into enemy territory, un-opposed, on schedule, and in tact. The next days march, as planned, would bring them to favorable ground on which to face the enemy; ––General Lee’s army of 61,000 men. But General Robert E. Lee never did what his opponents expected, and he attacked before the Army of the Potomac could reach that favorable open ground. In the dense tangled jungle forest called the Wilderness, the Federal advantage in men and matériel was rendered meaningless. The subsequent battles of May 5 & 6 dissolved into a bloody stalemate with 17,000 Union army casualties. What went wrong? Some of my takeaways from studying the battle, list the following mistakes: altered plans, faillure of the cavalry to do its job properly, and impenetrable terrain, with a few of the usual command & control problems thrown in. These shortcomings contributed to the poor outcome of the Union effort. I’ll briefly outline these problems one at a time. Altered Plans

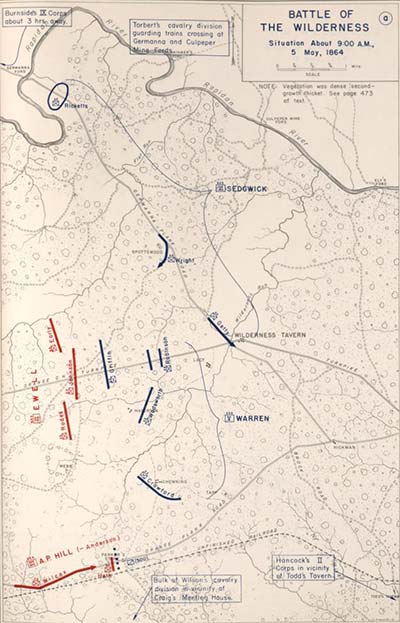

The original plans for the march drawn up by General Meade’s Chief of Staff, General Andrew A. Humphreys, [pictured] brought the armies beyond the forests of the Wilderness on May 4th. These plans were altered. So, the army stopped 5 miles short of its objective to keep within closer support of the slow moving supply wagon train. “If the movement to New Hope Church and Robertson’s tavern as indicated by General Humphreys, had been executed, the Army of the Potomac would have been placed in contact with the Army of Northern Virginia at daylight of May 5th, on comparatively favorable ground.” So wrote the author William H. Powell, in “The History of the Fifth Corps.” General Humphreys himself wrote, “The troops may have easily continued their march five miles farther…” Too much worry about the supply train risked fighting in the woods, which is what occurred.#1 General Grant didn’t really care where he encountered General Lee’s army, as long as it wasn’t in his strong defensive works. But the woods of the Wilderness hampered Grant’s desired objective and confounded General Meade’s efforts to consolidate his larger attack force. He wasn't able to bring the full weight and power of the Union Army's resources to bear against the enemy. Failure of the Cavalry Scouts General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick’s failed cavalry raid to Richmond ruined his chances at a presumed promotion. Instead Kilpatrick was transferred to the Army of the Cumberland. General Grant upon assuming command of all the armies, installed his own officers to command the Federal Cavalry Corps, and Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division was re-organized. Brigadier-General James H. Wilson came from the west to replace Kilpatrick. And it was unfortunately this division that General Sheridan assigned to screen the army's advance. Wilson had never led cavalry. His appointment necessitated transferring two experienced higher-ranked brigade commanders into other divisions. A new colonel was put in command of one brigade, while Gen. George Custer’s brigade was removed entirely and replaced with another. In short, the re-organized division didn’t yet have the cohesion and camaraderie between troops and commanders that comes with time and experience in the field. Wilson commanded the smallest of the Army of the Potomac's 3 Cavalry Divisions. Some of Wilson's mistakes were critical. General Phil Sheridan and his Cavalry Division Commanders. Re-organized Cavalry Command: left to right, Brigadier General Henry E. Davies, Jr., who out-ranked Wilson and was transferred out of Kilpatrick's 3d Division to the 2nd Cavalry Division; Brigadier-General David McMurtrie Gregg, commanded 2nd Cavalry Division, Major-General Sheridan, Brigadier-General Wesley Merritt was transferred from the 1st Division (formerly the late John Buford's) to the Cavalry Reserve Brigade; Brigadier-General Alfred Thomas Archimedes Torbert took command of the 1st Division and Brigadier-General James H. Wilson, seated, a former aid to U.S. Grant, replaced Kilpatrick in command of the 3d Cavalry Division. On May 4th, Wilson’s force cleared the path for Genral G. K. Warren’s 5th Corps to reach its destination, Wilderness Tavern. Wilson was at the Lacy farm about 8.30 a.m. [called Ellwood––B.F.] and sent patrols from there, over roads west and south. When Warren’s lead elements appeared on the scene, Wilson ordered his scouts on the Orange Turnpike to ride to Robertson’s Tavern, (called Locust Grove), to clear away any enemy scouts encountered. After giving these orders Wilson’s main body of cavalry rode to Parker’s Store on the Orange Plank Road, a few miles to the south. They reached Parker's about 2 p.m. Then Wilson sent the 5th New York Cavalry west down the road to patrol in the direction of Lee's army. The rest of the division bivouacked for the night at Parker’s.  This U.S. Military Academy map, published 1962, shows the position of Wilson's Cavalry at Parker's Store and the relative positions of the Confederate Corps of Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill in relationship to Warren and Hancock's Army Corps, on the evening of May 4th. Wilson had sent scouts down the Turnpike in the early afternoon, but about dusk they left to join the rest of their division at Parker's without noticing Ewell's advance to Locust Grove, [Robinson's Tavern]. Click to view larger. The Turnpike scouts had a small skirmish at at Robertson’s Tavern, then rode a bit further west towards Mine Run Creek. At dusk, the afternoon of the 4th, they left the Turnpike and rode across country from Robertson's Tavern to join the rest of the division at Parker’s Store. Morris Schaff wrote, “The chances are that their dust had barely settled before on came Ewell.” Soon after this patrol left the Orange Turnpike, General Richard Ewell’s Confederate Division advanced 2 miles east past Robertson’s Tavern, and camped within 2 miles of General Warren’s 5th Corps––unknown to anyone. Robertson's / Robinson's Tavern on the Orange Turnpike at Locust Grove

Robertson, or properly Robinson's Tavern on the Orange Turnpike, Locust Grove, VA. The structure still stands today, but has been moved a short distance away. The well pictured here, still exists on the original site; capped. A gas station & strip mall occupy the historic location today. Photo taken in 1910 by Frank Happel, National Park Historian, Fredericksburg. Wilson’s message to his superiors the evening of May 4th, reported the roads were clear. In fact the Orange Turnpike was completely unguarded. Wilson assumed that General Warren's 5th Corps infantry would send out its own pickets to protect their bivouack. Yet he failed to tell this to General Warren, who naturally expected the cavalry to be out paroling the roads and protecting his flank. Warren had no idea the enemy was so close. His pickets only extended a mile west down the road from Old Wilderness Tavern. At 8 p.m. General Meade sent a message to General Wilson exhorting him to keep patrols out to protect both roads. Wilson says he never received the message. Morris Schaff, considering all this writes, “Had they stayed at Locust Grove a few hours longer, what would have happened? Why, the orders issued at 6 o’clock would have been countermanded at once. Warren and Sedgwick would have struck at Ewell early in the morning, and Hancock, instead of going to Todd’s Tavern, would have reached Parker’s store by sun-up, and probably before noon a great victory would have been won.” #2 Another Problem: Impenetrable Terrain The army already knew from past experience the Wilderness was a terrible place to maneuver troops or fight a battle. The landscape favored defensive actions. One example of this would be General Horatio Wright's one and a half mile march through the woods to link up with the 5th Corps near Saunders Field on May 5th. At 11 a.m., Wright’s Division of the 6th Corps advanced down Spotswood Road [or, Culpeper Mine Ford Road––B.F.] to connect with General Warren’s lines north of the Orange Turnpike. A small force of Confederate skirmishers, probably the 1st North Carolina Cavalry, delayed the advance for several hours! Confederate skirmishers were able to delay the Union link up, forcing Warren’s divisions to attack Gen. Ewell's Corps alone, and without support. General Richard Ewell wrote in his campaign report: “Next morning [May 5] I moved down the pike, sending the First North Carolina Cavalry, which I found in my front, on a road that turned to the left toward Germanna Ford.” #3 Author George T. Stevens [77th N.Y. Infantry ––B.F.] described the difficulty of getting down the Culpeper Mine Ford Road, and the effectiveness of the Rebel skirmishers. “At eleven o’clock the corps faced to the front, and advanced into the woods which skirted the road. …The wood through which our line was now moving was a thick growth of oak and walnut, densely filled with a smaller growth of pines and other brushwood; and in many places so thickly was this undergrowth interwoven among the large trees, that one could not see five yards in front of the line. Yet, as we pushed on, with as good a line as possible, the thick tangle in a measure disappeared, and the woods were more open. Still, in the most favorable places, the thicket was so close as to make it impossible to manage artillery or cavalry, and, indeed, infantry found great difficulty in advancing, and at length we were again in the midst of the thick undergrowth.  Artist Correspondent Edwin Forbes sketched the 6th Corps fighting in the woods of the Wilderness. Steven's cont'd: “We thus advanced through this interminable forest more than a mile and a half, driving the rebel skirmishers before us, when we came upon their line of battle, which refused to retire.” #4 The landscape was equally bewildering for an attack force. Author William H. Powell in his history of the 5th Corps described what the fight was like enveloped in such a landscape. “The peculiar nature of the ground fought over made this a weird, uncanny contest––a battle of invisibles with invisibles. There had been wood-fights before, but none in which the contestants were so completely concealed as in this. Here nothing could be seen of the enemy or his doings but the white smoke that belched out of the bushes and curled and wreathed in fantastic designs as it slowly floated upward through the hot air, for it was a very sultry day. The tremendous roll of the firing shut out all other sounds. Here and there a man toppled over and disappeared, or, springing to his feet, pressed his hands to the wounded part and ran to the rear. Men’s faces were sweaty black from biting cartridges, and a sort of grim ferocity seemed to be creeping into the actions and appearance of every one within the limited range of vision. The tops of the bushes were being cut away by the leaden missiles that tore through them, and occasional glimpses of gray, phantom-like forms, crouching under the bank of cloud were obtained.” #5 Another 5th Corps officer in General Ayres' Brigade wrote about their attack on the north side of the turnpike at 1 p.m.: “The forward-march by company-front through the underbrush interwoven with wild grapevines and other creepers, soon became almost impossible. I remember that, in order to break an avenue for my own company, I pushed ahead with my back to the front, forming a passage for my men, who rushed after me in single file, as soon as possible, but without regard to the original formation of the company. As soon as we reached a clearing large enough for the purpose, we would re-form again on the run and try to re-establish the connection with the companies to the right and left of us. Thus we moved forward, unable to see anything else in front of us but tree-trunks and underbrush. I had just noticed that the right company of my regiment, and a few files of the right of my own company were going out of sight, diagonally to the front, losing the touch towards the road and to the left. I called to them with all my might in order to bring them back, but they either could or would not hear me, and we parted company right then and there. The next time I saw some of these men was at the close of the war, when they returned from Southern prisons.” #6 Command Problems 1: Failure to Co-operate The surprise encounter with the Rebels on the morning of May 5th didn’t disturb General Grant too much, he was determined to fight General Lee where ever he found him, but the inability of the Eastern generals to coordinate an attack did bother him, as hours of inaction passed by and the morning slipped into mid-day. The Army of the Potomac commanders couldn’t seem to co-operate with each other and had a great deal of difficulty assembling for an assault. General Warren hoped to attack when the promised 6th Corps troops from General Sedgwick's command arrived to support a charge. But these troops promised to Warren at 9 a.m. didn't receive orders to start on the march until 11 a.m. When they were underway, the enemy, as mentioned above, took every means to bushwack and delay their progress in the deep woods. General Meade informed General Grant at 7.30 a.m., “The enemy have appeared in force on the Orange pike, and are now reported forming line of battle in front of Griffin’s division, Fifth Corps. I have directed General Warren to attack them at once with his whole force.” Meade wrote to Grant again at 9 a.m., this time getting a little cocky at the end of the message, “Warren is making his disposition to attack, and Sedgwick to support him. Nothing immediate from the front. I think, still, Lee is simply making a demonstration to gain time. I shall, if such is the case punish him.” #7 Meade was probably trying to impress upon the new Commanding General of the Armies that he could be aggressive as needed. But the bold words fell flat. Meade and his officers decided at 9 a.m. General Wright’s Division of the 6th Corps would move down Spotswood / Culpeper Mine Ford Road, ––a shortcut through the Wilderness running from Spotswood Plantation to Saunders Field, to support Warren’s attack. The 6th Corps was perfectly poised to do so. It was not until 11 o’clock however, 2 hours later, that Wright’s Division was ordered forward. Confederate bushwackers further delayed their progress.    General G. K. Warren, Engineer Washington Roebling, and General Samuel W. Crawford. Gen. Warren meanwhile had a difficult time lining up his own 3 divisions for battle. General Samuel Crawford in command of Warren’s lead division, did not want to vacate his advanced position on the Chewning Farm, closeby to the morning's designated destination of Parkers Store. He and General Warren’s Chief Engineer, Major Washington Roebling, concurred that it was a key strategic position, situated on a hill commanding the Orange Plank Road, (upon which the enemy was advancing) so they both resisted Warren’s 11.15 a.m. orders to give up the field and move north to connect with General James Wadsworth's Division. To the contrary, Roebling was requesting General Warren send reinforcements to General Crawford! Roebling wrote Warren during the morning, “It is of vital importance to hold the field where General Crawford is. Our whole line of battle is turned if the enemy get possession of it. There is a gap of a half a mile between Wadsworth and Crawford. He cannot hold the line against an attack.”  The Chewning Farm, taken from the location of the farm house that stood during the battle, looking north, in the direction Crawford was supposed to move to link up with Wadsworth's Division. Warren, under increasing pressure from General Meade to attack, replied at 11.50 a.m., “You must connect with General Wadsworth, and cover and protect his left as he advances.” Finally at noon, Crawford began to comply with Warren’s directive.#8 To the north of Crawford, General James Wadsworth was hampered by the dense woods in his effort to connect his right flank with General Charles Griffin's Division at Saunders Field. And General Griffin’s subordinates directly in front of the enemy were counseling Warren to wait until re-enforcements from the 6th Corps arrived before they made any attack. They observed the enemy digging in and expressed to Warren that an isolated charge against well built earthworks by a single division would be futile. Lt.- Colonel William Swan, a staff officer who was on the ground with General Griffin's troops the morning of May 5th wrote: “I know that generals and staff officers all thought that the enemy was in strong force. I remember that word to that effect was sent back to General Warren, and I am sure that not long after I knew that Griffin had been ordered to attack. I think I carried the order from Griffin to Ayres to attack. I remember that Ayres sent me back to Griffin to say that in his judgment we ought to wait, for the enemy was about to attack us and we had a strong position; and I remember that Griffin went again to the front, and then sent me back to say to General Warren that he was averse to making an attack. I don’t remember his words, but it was a remonstrance. I think I went twice to General Warren with that message. The last time I met him on the road, and I remember that he answered me as if fear was at the bottom of my errand. I remember my indignation. It was afterwards a common report in the army that Warren had just had unpleasant things said to him by General Meade, and that General Meade had just heard the bravery of his army questioned.” #9

Brigadier-Generals Charles Griffin, commanding 1st Division, 5th Corps, and General Romeyn B. Ayres, commanding Griffin's 1st Brigade. Today, hindsight is everything, but General Warren, with his commanders reporting directly to him that a strong enemy force was in their front, was correct in his assessment of the situation. Warren was convinced that the impatience of Grant and Meade cost them a victory. Years later he wrote in a letter: “Meade and Grant, thought it only an observing brigade of the enemy opposed to me that we might scoop and that by taking time they would get away.” ”We had no certain means of knowing the strength of the rebel force. It would do well to move only with matters well in hand, as the repulse of my force would make a bad beginning.’ Warren reminded Meade, “that the 6th Corps was coming up on my right and that if time would be given them to get in position, as soon as they announced this by attacking I could move with my whole force against their front.” According to Warren Meade sternly replied. “We are waiting for you.” #10 Author Gordon C. Rhea summarized in his 1990 study of the battle: “The attack up the turnpike would be made not by two corps, as Meade had earlier planned, but by two divisions forming a wavering line across nearly two miles of woodland, both flanks open to the enemy. Six hours after Meade’s first order to attack, Warren was at last going forward.” #11 Grant and Meade criticized Warren’s behavior at the Wilderness, but Warren was right and the attack proved bloody and accomplished nothing. In his post-war assessment of things, General Warren reasoned, “Hill would have stood alone and nothing except retreat could save him. Longstreet was not up, and if Gen. Lee had made any attempt to hold on at the Wilderness, we should have finished him there. This is not an afterthought of mine, I saw it at once at the time.” #12 Command Problems II: Divided Command; General Burnside & the 9th Corps General Burnside ranked General Meade so General Grant chose to direct Burnside’s 9th Corps as a separate army. The protocol failed. Author Gordon C. Rhea writes, “On May 5, Burnside stood idle while the nearby 6th Corps sustained fearful losses.” “Grant’s failure to hurry Burnside to Wright’s assistance––and a momentous failure it was, considering that the added weight of Burnside’s three available divisions would have materially advanced the chances of shattering Ewell’s line––remains one of the Wilderness campaign’s mysteries. Surviving contemporaneous sources only deepen the puzzle, since they unequivocally confirm that Grant intended Burnside to lend Wright a hand if it was needed.” At 3 p.m. Grant messaged Burnside, “If General Sedgwick calls on you, you will give him a division.” Burnside replied, “General Potter’s division will soon be up, and I will hold him subject to General Sedgwick’s request.” #13

George T. Stevens wrote in his history of the 6th Corps, “At half-past three o’clock our sufferings had been so great that General Sedgwick sent a messenger to General Burnside, who had now crossed his corps at Germania Ford, with a request that he would send a division to our assistance. “The assistance was promised, but an order from General Grant made other disposition of the division, and what remained of the noble old Sixth corps was left to hold its position alone. At four, or a little later, the rebels retired, leaving many of their dead upon the ground, whom they were unable to remove.” #14 There was another failure with the divided command. When General Grant decided upon his excellent plan to attack in Hancock’s sector in the early morning hours of May 6, General Burnside’s Corps had a crucial part to play. Grant’s instructions to him were explicit. “Lieutenant-General Grant desires that you start your two divisions at 2 a.m. tomorrow, punctually for this place. You will put them in position between the Germanna plank road and the road leading from this place to Parker’s Store, so as to close the gap between Warren and Hancock, connecting both. You will move from this position on the enemy beyond at 4.30 a.m., the time at which the Army of the Potomac moves.” #15 Burnside’s mission was to assault A. P. Hills flank. “According to an aide after Meade’s review of the projected offensive, Burnside rose grandly to his feet. The commander of the 9th Corps cut an impressive figure. Burnside, throwing his soldiers back assumed a thoughtful look. He declared resoundingly, “Well, then, my troops shall break camp by half-past two!” The assembled generals did not miss the fact that Burnside had added a half hour to the starting time assigned by Grant. The deviation, however, did not seem of consequence to the 9th Corps commander. With measured step, he threw open Meade’s tent flap and strode into the night. As soon as he disappeared, knowing looks passed around the table. Meade’s chief of engineers, Major James C. Duane, leaned forward and stroked his rusty beard. “He won’t be up––I know him well,” Duane reportedly whispered.” #16 Burnside was not in place to attack until 2 p.m in the afternoon on May 6th. Even after the designated start time for the attack was delayed a half-hour, for his benefit, from 4.30 to 5 a.m., he was nine hours late. Theodore Lyman, Gen. Meade’s volunteer aid recorded in his diary: May 6, Friday, All hands up before daylight. Sunrise was at about 4.40. The General [Meade––B.F.] was in the saddle in the gray of the morning. As he sat in the hollow by the Germanna Plank, up comes Capt. Hutton of Burnside’s staff and says only one division was up and the road blocked with artillery (part of which was then passing us). ––The General uttered some exclamation, and Hutton said: “if you will authorize me sir, I will take the responsibility of ordering the artillery out of the road, and bring up the infantry at once.” ––“No Sir” said Meade flatly. “I have no command over Gen. Burnside.” #17 The attack plan was important and Gen. Meade should have taken the initiative here. Lyman was sent to General Hancock’s sector of the battlefield to monitor its progress. Hancock attacked as planned. At 5.40 a.m. Lyman wrote to General Meade, “General Hancock went in punctually, and is driving the enemy handsomely.” If Burnside had been in place, the Federals could have driven the Confederates from the battle field before General Longstreet's reinforcements arrived later in the morning. Longstreet's arrival changed the dynamic of the battle in Hancock's sector. At 6.30 a.m. Lyman wrote to General Meade, “General Hancock requests that Burnside may go in as soon as possible. As General Birney reports, we about hold our own against Longstreet, and many regiments are tired and shattered.” Again, Burnside didn’t get into position and attack until 2 p.m. It was by then far too late to have the desired effect. “Burnside did little more than pecked at Hill and Longstreet.” #18 The split command between Burnside and Meade had terrible consequences for the army. And Gen. Meade failed when he refused to take action to try and hurry Burnside along. Perhaps Gen. Meade had a strong understanding about the touchy relationships between comanders when he said he had no command over Burnside. Otherwise it seems he would have done something. But it seems a shame he didn't try, considering the consequences that hung in the balance. Command Problems III: Jumbled Troops   Brigadier-General Alexander Webb. commander 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, 2nd Army Corps. Brigadier-General James S. Wadsworth, commander 4th Division, 5th Army Corps. The third leadership problem at the Battle of the Wilderness was the jumble of mixed commands. So many brigades and divisions were mixed between the four army corps by necessity, that it was difficult to get unit cohesion from the troops on the ground. General Alexander Webb’s narrative later on the page speaks directly to this issue. One example: When General Wadsworth appeared on the scene, [4th Division 5th Corps] he took command of Webb’s 12 regiments, which included some 9th Corps troops, as well as Webb’s 2nd Corps Brigade. Wadsworth sent Webb on a silly errand, before understanding the strategic importance of Webb’s position, and then launched a foolish charge that got himself mortally wounded. The story speaks for itself. According to Gen. Webb, whose bitterness comes through in his post-war account, his men prepared a strong earthwork to prevent the enemy from advancing beyond its crucial location. Webb told them to hold the works at all cost. But Gen. Wadsworth arrived and ordered Gen. Webb away on a scout. Wadsworth rode up, and ordered Webb's men over the works to charge forward. They explained the importance of their position to Gen. Wadsworth who accused them of cowardice for not wanting to leave the protection of their fortifications. In a show of bravado, Wadsworth leapt over the defenses saying he would charge himself. Not to be out done, Webb's proven troops followed the general to the attack. This resulted in a lot more men getting killed, including Wadworth himself. Aftermath - Morale & Casualties In his narrative, General Webb commented on the devastating impact the battle had on the morale of the soldiers. “From personal contact with the regiments who did the hardest fighting, I declare that the individual men had no longer that confidence in their commanders which had been their best and strongest trait during the past year.”

Lieutenant Morris Schaff, an aide with General Warren, penned his own battle history and solemnly summed up the situation at battles end. Author Morris Schaff, left, was a young officer recently graduated from the Military Academy at West Point when he joined active service. He wrote many books. Here he is pictured as an older man. “Two days of deadly encounter, every man who could bear a musket thad been put in; Hancock and Warren repulsed, Sedgwick routed, and now on the defensive behind breastworks; the cavalry drawn back; the trains seeking safety behind the Rapidan; thousands and thousands of killed and wounded,… and the air pervaded with a lurking feeling of being face-to-face with disaster. What, what is the matter with the Army of the Potomac? #19 Casualties were so high they were fudged by at least one general. G. K. Warren was observed at his headquarters desk brooding over the reported losses. His aide, Lieutenant Morris Schaff tells the story. It is the night of May 5th at the Lacy House. “After supper, which did not take place until the day’s commotion had well quieted down, I happened to go into the Lacy house, and in the large, high-ceiled room on the left of the hall was Warren, seated on one side of a small table, with Locke, his adjutant general, and Milhau, his chief surgeon, on the other, making up a report of his losses of the day. Warren was still wearing his yellow sash, his hat rested on the table, and his long, coal-black hair was streaming away from his finely expressive forehead, the only feature rising unclouded above the habitual gloom of his duskily sallow face. A couple of tallow candles were burning on the table, and on the high mantel a globe lantern. Locke and Milhau were both small men: the former unpretentious, much reflecting, and taciturn; the latter, a modest man, and a great friend of McClellan’s, with a naturally rippling, joyous nature. The room at Ellwood used by General Warren, exactly as Lt. Schaff described it. “Just as I passed them, I heard Milhau give a figure, his aggregate from data which he had gathered at the hospitals. “It will never do, Locke, to make a showing of such heavy losses,” quickly observed Warren. It was the first time I had ever been present when an official report of this kind was being made, and in my unsophisticated state of West Point truthfulness it drew my eyes to Warren’s face with wonder, and I can see its earnest, mournfully solemn lines yet. It is needless to say that after that I always doubted reports of casualties until officially certified. Shortly after, Warren, accompanied by Roebling, went to a conference of the corps commanders which Meade had called to arrange for the attack which Grant had already ordered to be made at 4.30 the next morning.” #20 The Battle in the Wilderness cost both sides heavily. Irreplaceable was the loss of experienced veteran solders. The bloodletting continued through to early June. By the end, both armies were wholly changed from that with which they had begun. NOTES. May 4th, 1864: The River CrossingHere begins the chronology of the Campaign. Prologue: Memoirs of George Kimball, 12th MA Excerpt from “My Army Life,” by George Kimball; Boston Journal, June 10, 1893. In May the spring campaign began. At midnight on the 3d we broke camp and marched to the Rapidan. At noon next day that stream was crossed at Germanna Ford. Then began a series of battles that lasted up to the very day our term expired. We had still 52 days to serve, but our thoughts now traveled homeward, and we reminded each other of the welcome fact that the day was not far distant when we would greet wives and mothers and other dear ones. We were living in the future while conscious of a present that gave small promise indeed of the fulfillment of our desires. We dreamed of our homes when sleep was permitted and talked of them incessantly amid the roar of artillery and the rattle of musketry. Many, oh how many of those good, brave fellows were to find graves in the depths of the forests that lay in our bloody pathway to the James! How many, of them were to die that the nation might live, with the love of kindred and friends so strongly moving them to heroic deeds! As I write, their faces come back to me again, and I see them once more, as, lighted by love of home and love of country, they press forward at the word, never faltering, never seeking to spare themselves, for to true men honor is dearer than everything else, and stronger even than human ties. 1 shall not attempt to describe the great battles through which we passed in our journey to Petersburg, for I must bring my long story to a close. On the 5th, in The Wilderness, seven of our men were killed and 50 wounded. The next day five more gave up their lives and 20 were wounded, and on the 7th two were killed and four wounded. Letter to General Grant from President Lincoln Executive

Mansion,

Lieutenant-General Grant Not expecting to see you again before the Spring campaign opens, I wish to express, in this way, my entire satisfaction with what you have done up to this time, so far as I understand it. The particulars of your plans I neither know, or seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant, and pleased, with this, I wish not to obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you. While I am very anxious that any great disaster, or the capture of our men in great numbers, shall be avoided, I know these points are less likely to escape your attention than they would be mine. If there is anything wanting which is within my power to give, do not fail to let me know it. And now with a brave army, and a just cause, may God sustain you. Yours very truly,

History of the 13th Massachusetts, Charles E. Davis, Jr. The following is from, “Three Years in the Army,” by Charles E. Davis, Jr; Estes & Lauriat, Boston, 1894. Wednesday, May 4, 1864. “On to Richmond” was once more the cry. Joined the Second Division of the Fifth Corps near Culpeper, continuing our march, crossing the river at Germanna Ford, halting at 3.30 P.M. on the south side of the plank-road about two and a half miles from Robertson’s tavern. [I think Davis may mean Wilderness Tavern––B.F.] The weather was hot and the roads dusty. The distance covered was twenty-two miles. The whole army was on the move, and an imposing spectacle it must have been to the lookers-on. The men carried six days’ rations. Two and a half months more and we should be marching toward Boston unless we took up our residence, before that time, in the “promised land.”

Edwin Forbes sketch titled, “The Supply Train,” Few persons, even soldiers, have any idea of the size of a wagon train required to feed, clothe, and provide ammunition for an army numbering a hundred thousand men, say nothing of the ambulances, the wagons for transporting the hospital stores, the baggage of officers, and the books and papers necessary to each regiment. It is said that General Grant’s wagon train if stretched out in a continuous line would reach a distance of one hundred miles. It was an interesting sight to see a “wagon park.” Five hundred wagons, arranged in lines as straight as soldiers on dress parade, were frequently to be seen at the headquarters of the chief quartermaster, where also might be seen harness-makers, all in full operation, where hundreds of horses and mules were shod every month, and wagons and harnesses repaired. A park of five hundred wagons meant a collection of not less than two thousand mules. Multiply the noise made by one mule by two thousand, and you can judge how little chance there is for sleep within a radius of ten miles.  General Meade Addresses the Army, May 4th Headquarters

Army of the Potomac, Soldiers: Again you are called upon to advance on the enemies of your country. The time and the occasion are deemed opportune by your commanding general to address you a few words of confidence and caution. You have been reorganized, strengthened, and fully equipped in every respect. You form a part of the several armies of your country, the whole under the direction of an able and distinguished general, who enjoys the confidence of the Government, the people, and the army. Your movement being in coöperation with others, it is of the utmost importance that no effort should be left unspared to make it successful. Soldiers ! the eyes of the whole country are looking with anxious hope to the blow you are about to strike in the most sacred cause that ever called men to arms. Remember your homes, your wives and children, and bear in mind that the sooner your enemies are overcome the sooner you will be returned to enjoy the benefits and blessings of peace. Bear with patience the hardships and sacrifices you will be called upon to endure. Have confidence in your officers and in each other. Keep your ranks on the march and on the battlefield, and let each man earnestly implore God’s blessing, and endeavor by his thought and actions to render himself worthy of the favor he seeks. With clear consciences and strong arms, actuated by a high sense of duty, fighting to preserve the Government and the institutions handed down to us by our forefathers ––if true to ourselves ––victory, under God’s blessing, must and will attend our efforts. GEO G. MEADE,

About this order, Private Bourne Spooner, Company D of the 13th Mass, wrote in his diary: [May 3] Map of the March

Map of prominent landmarks on the march of the First & Second Brigades of General Robinson's Division, to Germanna Ford, from their respective starting positions. Colonel Leonard's First Brigade was separated from the rest of the Division during the Winter Encampment. The Division consolidated during the march May 4th. A third Brigade of Maryland troops commanded by Colonel Andrew W. Denison hd been added to the division, It is not indicated on this map but started from the vicinity of Culpeper. History of the 39th Massachusetts, Alfred S. Roe Alfred Roe gives more details in this description of the 1st Brigade's march from Mitchell's Station, to Pony Mountain, to Stevensburg, etc. Included is a very brief mention of Virginia's Colonial Governor, Alexander Spotswood, (pictured below), for whom, Spotsylvania, Germanna Ford, and the Wilderness derived their respective names. By the way, there is only one "T" in the name, though the soldiers often spelled it with two. Spotswood is a fascinating, often amusing character full of ambition, fantastic schemes, fantasy dream houses and more. His dynamic personality often irritated his contemporary colonial and royal associates. He is worth far more exploration than is appropriate to present here, –––for those interested The following is from, “The Thirty-ninth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862-1865;” by Alfred S. Roe, 1914. THE MARCH May 4th, 1864. At first our own course is northward toward Culpeper, then we bear off to the right, passing the headquarters of the Sixth Corps, and those of the Army of the Potomac skirting the base of Pony Mountain and on to Germanna, remembered well in our Mine Run campaign. Though nominally, for several days a part of the Fifth Corps, we do not actually meet any part of the Corps itself till just before reaching the ford. We cross the river at about 11 a. m., nowhere encountering any opposition from the enemy, who evidently is endeavoring to ascertain what Grant’s objective may be, catching up with the other portions of the the Corps late in the afternoon. After an arduous march of considerably more than twenty miles, burdened by heavy knapsacks filled in winter quarters, our division bivouacked near the Wilderness Tavern.  Artist Edwin Forbes did this contemporary sketch of Wilderness Tavern and the battle-field along the Germanna [Plank] Road and Orange Turnpike. The tavern is long gone. Period Photos of the singular out-building on the right of the tavern exist, as does its chimney which still stands and is preserved by the National Park Service. The picture is cropped upon the left half of the panoramic drawing. In the foreground is the road to Chancellorsville, crowded with ambulances and wounded men. Wagons line the road in front of the tavern (difficult to see at this size). The Lacy House, which would be General G. K. Warren's Headquarters, is visible in the sketch on a hill to the right, but its been cropped out of this view. On the night of May 4th, General Sheridan & Staff were camped around the tavern. A strip mall stands in the foreground area today. A grassy divider to Modern Hiway, Route 3 runs through the site of the tavern. Remains of the Wilderness Tavern Dependency   Pictured at left is a dependency of the old Wilderness Tavern. It can be seen in the sketch above. The ruins of the same structure today, as preserved by the National Park Service, is pictured at right. The original Tavern stood in the background trees of the 2nd photo. Click here to view larger. Alfred Roe, continued: “From this point the almost countless campfires of our army could be seen, always an impressive sight, and never were the soldiers of the Potomac Army in a more impressible mood than after their long period in winter quarters. Of the troop thus in bivouac, Lieut. Porter of Company A wrote, “The men were in the best of spirits. They believed that the supreme effort to bring the rebellion to a close was being made. There were enthusiasm and determination in the minds of everyone. “A year ago the word “Wilderness” was frequently heard as the events of Chancellorsville were discussed and now it is to gain even wider mention; it seems a name quite out of place in the midst of the Old Dominion, not so far from the very first settlements in British North America.”

“General Morris Schaff in his story of the great battle says this of the section, “What is known as the Wilderness begins near Orange Court House on the west and extends almost to Fredericksburg, twenty-five or thirty miles to the east. Its northern bounds are the Rapidan and the Rappahannock and, owing to the winding channels, its width is somewhat irregular. At Spottsylvania, its extreme southern limit, it is some ten miles wide. “Considerably more than a hundred years before, there were extensive iron mines worked in this region under the directions of Alexander Spottswood, then governor of Virginia. To feed the furnaces the section was quite denuded of trees and the irregular growth of subsequent years, upon the thin soil, of low-limbed and scraggy pines, stiff and bristling chinkapins, scrub-oaks and hazel bushes gave rise to the appellation so often applied. Hooker and Chancellorsville are already involved in memories of the region and coming days will give equal associations with Grant and Meade, while the Confederates, remembering that within its mazes their own shots killed their peerless leader, Jackson, ere many hours have passed will lament a similar misfortune to Longstreet. “Within this tangled thicket, artillery will be of no avail and the vast array of thunderers will stand silent as artillerymen hear the roar of musketry; cavalry will be equally out of the question, but within firing distance more than two hundred thousand men will consume vast quantities of gunpowder in their efforts to destroy each other.” “It is generally understood that General Grant did not expect an encounter with Lee within the Wilderness itself, as is evident in Meade’s orders to Hancock and the Second Corps; indeed on the 5th the latter was recalled from Chancellorsville to the Brock Road at the left of the Fifth Corps, the Confederates having displayed a disposition to attack much earlier than the Union Commanders had thought probable; how Sedgwick and the Sixth Corps held the Union right, Warren and his Fifth the centre and Hancock with the Second were at the left are figures from the past well remembered by participant and student. While every movement of the Union Army has a southern tendency, a disposition to get nearer to Richmond, yet in the Wilderness all of the fighting was along a north and south line, the enemy exhibiting an unwillingness to be out flanked as easily as the new leader of the Potomac Army had evidently expected.”  Army of the Potomac Artillery Crossing the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford, May, 1864. Journal of Colonel Charles Wainwright, Chief of 5th Corps Artillery

The following is from, “A Diary of Battle; The

Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, 1861 ––1865.”

Edited by Allan Nevins; Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg,

PA, © 1962. Winslow's battery, mentioned in the text would play an important part in the battle. Old Wilderness Tavern, May 4, Wednesday. It was nearly two o’clock this morning when we got our orders to haul out. I had managed a few short snatches of sleep before that time, but do not improve in my ability to go off at any moment and in any place. There is a kind of weird excitement in this starting at midnight. The senses seemed doubly awake to every impression––the batteries gathering around my quarters in the darkness; the moving of lanterns, and the hailing of the men; then the distant sound of the hoofs of the aide’s horse who brings the final order to start. Sleepy as I always am at such times, I have a certain amount of enjoyment in it all. We got off without much trouble in order thus. Rittenhouse,

“D.” 5th U.S. -– 6 10 pdr. parrot Great care was taken not to make any more fires than usual, so as not to attract the attention of the enemy; otherwise the darkness and distance were a quite sufficient cover to our movement. Through Stevensburg, on towards Shepherd’s Grove for another mile or so, and then across country through a byroad, we had it all to ourselves. When we arrived at the head of the Germanna Plank Road we had to wait an hour for the two divisions which were to precede us to file by. It was nine o’clock by the time I reached the ford. After crossing, General Warren directed me to divide the batteries among the infantry divisions for the march through the Wilderness sending Cooper ahead with Crawford’s division which lead; (Martin, Phillips & Winslow with Griffin; Rittenhouse & Mink with Robinson; Breck & Stewart with Wadsworth.

I hated to break them up so on the first day’s march, before I had time to look after them all, but an unbroken string of artillery over a mile long was certainly somewhat risky through these dense woods. We moved on very slowly, although there was a division of cavalry ahead of us, and did not all get up here until near dark. The First and Third Divisions went into position immediately on the west side of the road; the 2d Div. formed on Griffins right the 4th on Crawfords left making a sort of semi-circle. Cooper, Martin, Phillips & Winslow were posted on the high ground around the house of Major Lacy, a really fine mansion standing on a knoll which commands the country in every direction. Pictured above is a period photo of the Lacy mansion, "Ellwood." The camera is looking at the north facade of the structure. Some of the dependencies are still standing in this image. That may be the plantation ice-house in the left foreground. The area is heavily wooded today. The other 4 Batt’s camped on the

east of the road we had come up by, around a tannery some half mile

before you reach the tavern: my own H’d Qts were hard by, &

Gen’l

Warren’s only a short distance off. The 6th Corps has crossed,

their

advance joining our right, –– Meades H’d Qts are with the

6th; Grant is still on the north of the river, ["A Bowery Boy," pictured; ––(N.Y. City Roughs.) ––B.F.] On the “Mine run” campaign I did not come to this point, which is the intersection of the Orange & Fredericksburg turnpike, with the Germania Plank road, as we cut across the corner through a by road. There is a large opening here of several hundred acres embracing the tavern, Maj Lacy’s & two or three other houses: all the rest of the country seems one vast wilderness of –– half grown pines & scrub oaks. Every thing so far has gone well; all has been done that was expected; one more day without interruption will put us where we want to be: but there is a big stir in Lee’s camps long before this no doubt, & we may run our noses against him at any time. My spring waggon broke down at the very start; the horses ran away with it & smashed the pole, so all the things had to go into the army waggon: Cruttenden sent the broken concern to be mended at once. We had no rain during the day; but some this evening, with a prospect of more during the night. I understand that all the other armies started today also: the campaigning opens with a combined move. Orders have just come for us to move tomorrow morning at five o’clock to Parker’s Store, on the Orange Court House Plank Road, the Sixth Corps moving up to this point. Captain Ludington and the Wagon TrainJournal of Theodore Lyman, May 4th 1864. General Meade's aristocratic aide and friend, Theodore Lyman relates the movements of Army Headquarters on May 4th. He describes the monumental effort to get the army across the Rapidan River without incident, which General Grant considered a great achievement in itself. He mentions quarter-master Marshall Ludington by name in this entry. The story of Captain Ludington's ordeal follows immediately, as it was told in John D. Billings' classic work about life in the Army of the Potomac, titled, “Hardtack & Coffee.”  s s The following is from, “Meade's Army, The Private Notebooks of Lt Col Theodore Lyman,” edited by David W. Lowe, Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2007. May 4, Wednesday.

7 a.m. The General unluckily came up with a cavalry waggon train, out of place; the worst thing for his temper! He sent me after its Quartermaster, Capt. Luddington, whom he gave awful dressing to, and ordered him to get his whole train out of the road and to halt till the other trains had passed. #1 The sun getting well up made the temperature much warmer, as was testified by the castaway packs & blankets with which troops will oft at the outset encumber themselves. 8 a.m. Arrived near Germanna Ford and halted just where we had camped the night of the withdrawal from Mine Run. Sapristi, [Good Heavens!] it was cold that night! Though here was green grass in place of an half inch of ice. Griffin’s division was over and his ammunition was then crossing. 8.30 a.m. News from Hancock that he was crossing, Gregg having had no oppositions and having seen only videttes. ––Roads everywhere excellent. [David M. Gregg's Cavalry Division screened the river crossing of Gen. Hancock's 2nd Corps at Ely's Ford. ––B.F.] 9.30. We crossed. There were two pontoons, a wooden & a canvass, the ascent up the opposite high and steep bank was bad, with a difficult turn near the top. #2 We halted just on the other side and Grant & his staff arrived some time after 12.15 p.m. All the 5th Corps, with its artillery and wheeled vehicles across. ––It began at 6.30 a.m. The 6th Corps began to cross at 12.40 and was all over at 5.20 and the canvas pontoon was taken up. A good part of the time, say ½, only one pontoon could be used, because the troops were moving in single column. We may then estimate 15 hours for the passage of 46,000 infantry, with one half of their ambulances and ammunition and intrenching waggons and the whole of their artillery, over a single bridge, with steep, bad approaches on each side; i.e. a little over 3,000 men an hour, with their artillery and wheels. The latter took a good deal of time because of the delay in getting them up the steep ascent. [Gen. Sedgwick's 6th Corps followed the 5th Corps at Germanna Ford. ––B.F.]  Sat on the bank and watched the steady stream, as it came over. That eve took a bath in the Rapid Ann and thought that might come sometime to bathe in the James! Our cook, little M. Mercier, came to grief, having been spirited away by the provost guard of the 2d Corps, as a straggler or spy so our supper was got up by the waiter boy, Marshall. Our camp was near the river, and Grant’s was close to us. Some of his officers; Duff & old Jerry Dent e.g. were very flippant and regarded Grant as already routing Lee and utterly breaking up the rebellion! ––not so the more sober. ––There arrived Gen. Seymour, the unlucky man of Olustee, dark bearded and over given to talk and write; but of well known valor. He was assigned to a brigade 3d Div. 6th Corps, where his command was destined to be of the shortest. #3 NOTES. [by David W. Lowe,

editor of Lyman's notebooks.] Captain Ludington

& General Wilson's

Cavalry Supply Train Here is another incident which will well illustrate the trials of a train quartermaster. At the opening of the campaign in 1864, Wilson’s cavalry division joined the Army of the Potomac.

Captain Ludington (now lieutenant-colonel, U. S. A.) was chief quartermaster of its supply train. It is a settled rule guiding the movement of trains that the cavalry supplies shall take precedence in a move, as the cavalry itself is wont to precede the rest of the army. Through some oversight of the chief quartermaster of the army, General Ingalls, the captain had received no order of march, and after waiting until the head of the infantry supply trains appeared, well understanding that his place was ahead of them on the march, he moved out of park into the road. At once he encountered the chief quartermaster of the corps train, and a hot and wordy contest ensued, in which vehement language found ready expression. Chief Quartermaster General Rufus Ingalls, poses with his horse and dog. Anyone who includes his horse and dog in their portrait is okay in my book. While the dispute for place was at white heat, General Meade and his staff rode by, and saw the altercation in progress without halting to inquire into its cause. After he had passed some distance up the road, Meade sent back an aid, with his compliments, to ascertain what train that was struggling for the road, who was in charge of it, and with what it was loaded. Captain Ludington informed him that it was Wilson’s cavalry supply train, loaded with forage and rations. These facts the aid reported faithfully to Meade, who sent him back again to inquire particularly if that really was Wilson’s cavalry train. Upon receiving an affirmation answer, he again carried the same to General Meade, who immediately turned back in his tracks, and came furiously back to Ludington. Uttering a volley of oaths, he asked him what he meant by throwing all the trains into confusion. “You ought to have been out of here hours ago!” he continued. “I have a great mind to hang you to the nearest tree. You are not fit to be a quartermaster.” In this manner General Meade rated the innocent captain for a few moments, and then rode away. When he had gone, General Ingalls dropped back from the staff a moment, with a laugh at the interview, and, on learning the captain’s case, told him to remain where he was until he received an order from him. Thereupon Ludington withdrew to a house that stood not far away from the road, and, taking a seat on the veranda, entered into conversation with two young ladies who resided there.

Soon after he had thus comfortably disposed himself, who should appear upon the highway but Sheridan, who was in command of all the cavalry with the army. On discovering the train at a standstill, he road up and asked:–– “What train is this?” “Captain Ludington.” “Where is he?” “There he sits yonder, talking to those ladies.” “Give him my compliments and tell him I want to see him,” said Sheridan, much wrought up at the situation, apparently thinking that the train was being delayed that its quartermaster might spend further time “in gentle dalliance’ with the ladies. As soon as the captain approached, the general charged forward impetuously, as if he would ride the captain down, and, with one of those “terrible oaths” for which he was famous, demanded to know what he was there for, why he was not out at daylight, and on after his division.

As Ludington attempted to explain, Sheridan cut him off by opening his battery of abuse again, threatening to have him shot for his incompetency and delay, and ordering him to take the road at once with his train. Having exhausted all the strong language in the vocabulary, he rode away, leaving the poor captain in a state of distress that can be only partially imagined. General Phil Sheridan, pictured right. When he had finally got somewhat settled after his rough stirring-up, he took a review of the situation, and, having weighed the threatened hanging by General Meade, the request to await his orders from General Ingalls, the threatened shooting of General Sheridan, and the original order of General Wilson, which was to be on hand with the supplies at a certain specified time and place, Ludington decided to await orders from General Ingalls, and resumed the company of the ladies. At last the orders came, and the captain moved his train, spending the night on the road in the Wilderness, and when morning dawned had reached a creek over which it was necessary for him to throw a bridge before it could be crossed. So he set his teamsters at work to build a bridge. Hardly had they begun felling trees before up rode the chief quartermaster of the Sixth Corps train, anxious to cross. An agreement was entered into, however, that they should build the bridge together; and the corps quartermaster set his pioneers at work with Ludington’s men, and the bridge was soon finished. Recognizing the necessity for the cavalry train to take the lead, the corps quartermaster had assented that it should pass the bridge first when it was completed, and on the arrival of that moment the train was put in motion, but just then a prompt and determined chief quartermaster of a Sixth Corps division train, unaware of the understanding had between his superior, the corps quartermaster, and Captain Ludington, rode forward and insisted on crossing first. Struggle for precedence immediately set in. The contest waxed warm, and language more forcible than polite was waking the woodland echoes when who should appear on the scene again but General Meade. On seeing Ludington engaged as he saw him the day before, it aroused his wrath most unreasonably, and, riding up to him, he shouted, with an oath: “What! are you here again!”

Then shaking his fist in his face, he continued: “I am sorry now that I did not hang you yesterday, as I threatened.” The captain, exhausted and out of patience with the trials which he had encountered, replied that he sincerely wished he had, and was sorry that he was not already dead. The arrival of the chief quartermaster of the Sixth Corps, at this time, ended the dispute for precedence, and Ludington went his way without further vexatious delays to overtake his cavalry division.

There never was a corps better organized than was the quartermaster’s corps with the Army of the Potomac in 1864. With a wagon-train that would have extended from the Rapidan to Richmond, stretched along in single file and separated as the teams necessarily would be when moving, we could still carry only three days’ forage and about ten to twelve days’ rations, besides a supply of ammunition. To overcome all difficulties, the chief quartermaster, General Rufus Ingalls, had marked on each wagon the corps badge with the division color and the number of the brigade. At a glance, the particular brigade to which any wagon belonged could be told. The wagons were also marked to note the contents; if ammunition, whether for artillery or infantry; if forage, whether grain or hay; if rations, whether bread, pork, beans, rice sugar coffee or whatever it might be. Empty wagons were never allowed to follow the army or stay in camp. As soon as a wagon was empty it would return to the base of supply for a load of precisely the same article that had been taken from it. Empty trains were obliged to leave the road free for loaded ones. Arriving near the army they would be parked in fields nearest to the brigades they belonged to. Issues, except ammunition, were made at night in all cases. By this system the hauling of forage for the supply train was almost wholly dispensed with. They consumed theirs at the depots. I left Culpeper Court House after all the troops had been put in motion, and passing rapidly to the front, crossed the Rapidan in advance of Sedgwick’s corps; and established headquarters for the afternoon and night in a deserted house near the river. Orders had been given, long before this movement began, to cut down the baggage of officers and men to the lowest point possible. Notwithstanding this I saw scattered along the road from Culpeper to Germania Ford wagon-loads of new blankets and overcoats, thrown away by the troops to lighten their knapsacks; an improvidence I had never witnessed before. Leonard's & Baxter's Brigades on the MarchSergeant Austin Stearns' Memoirs, 13th MA, Company K For the last part of his memoir, Sergeant Stearns would quote from his original field diary before each day's entry, and then elaborate. The following is from, “Three Years With Company K,” by Sergeant Austin C. Stearns, (deceased) Edited by Arthur Kent; Associated University Press, 1976. Wednesday the 4th “Fair, a pleasant day, routed up at 1 A.M. to strike tents and prepare for a march. Marched at half past two towards Culpeper, turned off and went to Stevensburg. From there to Germania Ford, crossed and went to near Wilderness Tavern. Bivouacked at 4 P. M. Marched about 24 miles. One of the hardest marches.” My recollections of this day are very fresh. The day was warm, and we were heavily loaded when we started, but as the day advanced the boys commenced to throw away their things. Over coats and blankets went, knapsacks were over hauled, and extra stockings, drawers, old letters that the boys had treasured up, in fact any thing and every thing that could lighten the load.

Austin Stearns' sketch from his memoirs. At Stevensburg we came upon the camps of other Corps, and such sights of clothing as were there, and all the rest of the way. I commenced by throwing away drawers, stockings then tearing my blanket in two, cutting off the cape of my over coat, knowing from past experience that I should need them in a few days. Some of the boys threw away every thing but their rations. Memoir of Major Abner Small, 16th Maine The following is from, “The Road to Richmond,” by Major Abner R. Small, edited by Harold A. Small, University of California Press, 1959. May 3d the expected orders to march was received; and at two o’clock in the morning of Wednesday May 4th, we started. Our division brought up the rear of Warren’s corps.  Under the bright stars our long column went north towards Culpeper Court House, then turned to the east and marched into a glorious spring day. Wild flowers were up; I remember them nodding by the roadside. Everything was bright and blowing. A little way beyond the clump of houses that was Stevensburg we topped a ridge commanding a wide view, and saw a splendid sight; all the roads were filled with marching men, the sunlight glinting on their muskets, and here and there on burnished cannon. We followed a narrow road that turned south into somber woods, and after a while we came to the Rapidan, crossed a pontoon bridge at Germanna Ford, and marched away from the swift stream into the green quiet of the Wilderness. The day had not been oppressively warm but in the narrow defile among the trees no air was stirring and the heat of the long marching under a heavy load provoked some of our men to throw away overcoats and blankets. We lost a few stragglers. When orders came down the line for us to halt and bivouac for the night we were nearing Wilderness Tavern. Diary of Sam Webster, Drum Corps, 13th MA “The Diary of Samuel

D. Webster”

Wednesday, May 4th, 1864 Are now the 3rd Division of the 5th Corps –– 1st Brigade. The 1st and 5th Corps are now consolidated, two divisions the 1st and 2nd being made from the 5th and two more, the 3rd and 4th divisions, from our old corps, the 1st. All of our 3rd division have been put into the 2nd (now 3rd Div of 5th corps) or into the 1st (now 4th div of 5th corps) : the badges being retained. [Sam is mistaken here. He is in the 2d Division of the 5th Corps, not the 3rd. This detail may not have been as obvious as one would think. His brigade was separated from the rest of the division and corps during the winter encampment at Mitchell's Station when the change was made.––B.F.] Diary of Corporal Calvin Conant, 13th MA The following is from the “Diary of Calvin Conant”

[Company G] Wednesday, May 4, 1864 March about 3 miles and stop for the night. Made about 20 miles to day feel tired and my feet are all blistered to day the sun shone hot and it was dusty.  Artist & War Correspondent Edwin Forbes sketched the army under General Hooker marching through the Wilderness a year earlier on May 2nd, 1863. Forbes was present again for General Grant's Campaign and would add some excellent sketches of the 1864 battle to his portfolio. Private Bourne Spooner's Journal, 13th MA The following is from The Journal of Private Bourne Spooner, Company D. From the Boston Public Library Special Collections. Transcribed by Bradley M. Forbush. Note the date of this entry. Dorchester Mass. Sat. July 23d 1864 A great deal of surplus clothing, tents, fry pans, post &c that had accumulated during the winter had to be left behind and half of what was taken was afterwards disposed with. The night was very dark yet at about One(?) o’clock the line was formed and the column put en route. Our direction lay along the Culpepper road and many supposed we were bound for the Rappahannock and Centreville, but as we proceeded on our course veered towards Pony Mountain which we doubled and marched then directly towards Germanna Ford. Pony Mountain viewed from a high hill at Stevensburg looking west. A few buildings stand, not visible in this image, where the road ends in the far distant middle-ground. They are the remains of the tiny hamlet of Stevensburg. The Baptist Church founded by Rev. Thornton Stringfellow sits atop the high ground. Rev. Thornton Stringfellow is buried here. If you re-read Major Abner Small's account above, he mentions the view from this hill. Pony Mountain is prominent in the background. It was the sight of a Union Lookout station. Lucky Stevensburg is soon to be favored with a modern data center, which will no doubt add to the quaint ambiance of the location. Private Spooner, cont'd: We again fell in, struck on to the plank road and

marched in to the Wilderness. That night after a

The Conscripts The number of men still serving in the "13th Mass" was not large coming in at just under 200 when they set out on the march. Their number was diminished by another seven who chose to desert. These were conscripts of August, 1863,who decided they would rather not participate in any upcoming battles and so took the opportunity to disapear. The last we heard of the conscripts was in April, when 24 or so transfered to the navy. Three more of them vanished on May 4th. They were Charles Wilson, age 23 of Company G, Thomas Sullivan, age 32, of Company I, and Theodore Thiel, age 31 also of Company I. Four others deserted on May 5th, all of them in Company A. Martin Gerity, age 26, Michael J. Giblin, age 21, Thomas Horton, age 23, and Charles Searles age 31. I count about 52 of the original 186 conscripts, in number who were still with the regiment. Several of them would die or be wounded in the coming battles. The remainder were transferred to the 39th MA in mid-July when the regiment concluded its term of service.